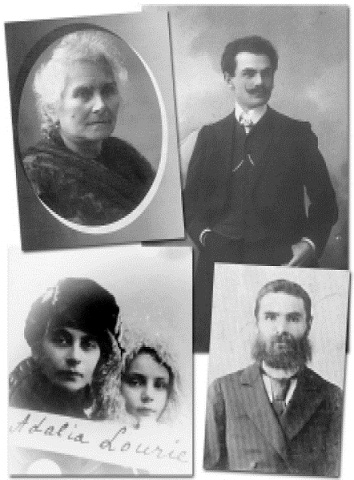

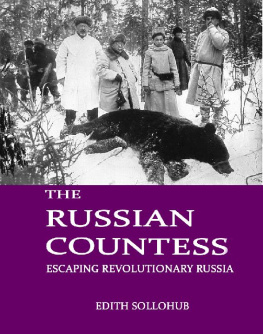

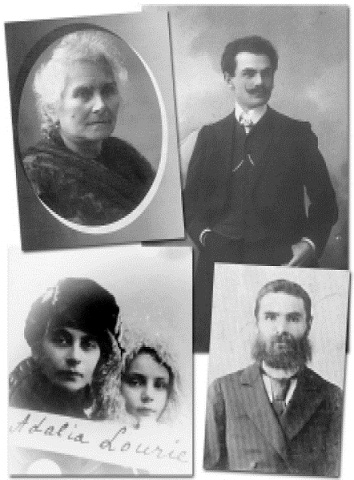

Clockwise from top left: Babushka, Papa (Adolf Lurye), Zeyde (Yefim Lurye) as a young man, Mamma (Olga lourie) and Niura.

Weather of the Heart

A Childs Journey Out of Revolutionary Russia

Nora Lourie Percival

High Country Publishers, Ltd

Boone, North Carolina

High Country Publishers, Ltd

197 New Market Center #135

Boone, NC 28607

www.highcountrypublishers.com

<>

Copyright 2001 by Nora Lourie Percival. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Percival, Nora, 1914

Weather of the heart : a childs journey out of revolutionary Russia / by Nora Percival.

p.; cm.

ISBN 0-9713045-9-9 (softcover : alk. paper)

1. Percival, Nora, 1914--Childhood and youth. 2. Jews--Russia (Federation)--Samara--Biography. 3. Samara (Russia)--Biography. 4. Percival, Nora, 1914--Journeys--Russia (Federation)--Samara.

I.

Title.

DS135.R95 P47 2002

304.87304744__dc21

2001004638

First Printing: February 2002

First Paperback Printing: February 2003

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

For my children and grandchildren,

who continue the story here begun,

and in whom the dear dead still have their being.

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been brought to fruition without the support and encouragement of many friends, relatives, and colleagues. The enthusiasm and advice of fellow members of the High Country Writers and the inspiration and generous assistance of my editor, Judy Geary, have been invaluable. I must also acknowledge the many hours of help and the stubborn patience of Schuyler Kaufman and the generosity of Bob and Barbara Ingalls. To all of them I express profound gratitude.

Contents

Foreword

In all the years this story has been gestating, I have often wondered at its stubborn insistence on being told, its refusal to sink gracefully into the gentle limbo of faint memory. So many times the writing has been put aside, sometimes even out of mind, for months or years; but always it has resurfaced, clamored, persisted. Until at last, the busy years of family and career demands being done, it rose to dominate my days, and finally emerged in words on paper.

It was a long process. Life takes us, moves us, uses us. A husband falls ill, grandchildren are born, the snowdrops and daffodils push up through the heavy mulch of leaves and demand attention to free them to grow. And while we answer the demands of people and plants, of houses and jobs and health and talent, our lives move on to new conditions, pulling us along perforce. While we dream of how we want to shape a life, we have already lived it, and it is gone.

Why then, in the midst of the engrossing now, why this passion to remember, this drive to resurrect the trials and crises of so long ago? Perhaps the need to acknowledge those enormous efforts to survive, to record them on the register of human struggles against dehumanizing forces. So many later catastrophes now overlay these ancient agonies could they still be relevant? Yet its always been the same struggle during revolutions, wars, holocausts, genocides, on whatever continent and in whatever era always the same struggle of the single human spirit against the massed baleful power of ideology.

In his book A View of All the Russias, Laurens van der Post says: No man is free to commit himself to an honest future until he has first been honest about the past. Though most of my future is now in the past, still this need to explore those desperate days persists. Before I cease to remember, it seems necessary to bear witness, to pass on to my descendants and to all the other descendants of the people who lived through those overwhelming events a sense of how it was. So aware of the power of history, I am impelled to show how much it shaped those who shaped and still shape todays young.

We take so much for granted. We see an old church, poised perfectly on a hill commanding the crossroads, its Wren steeple a lovely exclamation point in time. Do we ever think of how this spot was chosen, cleared, who it was that imagined the perfect site? So in our lives, we take for granted what people are, without dreaming of what made them so, what worlds shaped them.

This is the question I want to probe. What happens to people under severe duress, under continuing extreme pressure? Why do some individuals rise magnificently to the challenge, discover unsuspected powers that make them function better than before? While other uncertain souls, terrified in the face of their own inadequacy, with no confidence in their own will, withdraw from the battle and lose the chance to grow into strength, stamp themselves imperfect and useless and never test the extent of their powers. Their chances of survival are minimal, and if they do live, they are broken and helpless for the rest of their days.

Phyllis Rose wrote in Biography as Fiction: The way people manage to live their lives without prior rehearsal is amazing and insufficiently wondered at. In a crisis situation such as existed in Russia in the second and third decades of the last century, the way life was managed, especially by the millions caught helplessly between opposing forces in which they had no part, seems even more incredible.

Such a revolution is really a struggle between the powerful, such as nobles and wealthy landowners, on one hand, and the poor, tired of living on a bare minimum in an inefficient economy, on the other. Yet the growing middle class was in many ways the chief sufferer in the conflict. The triumphant proletariat tarred the bourjui with the same brush as the gentry, although the intelligentsia didnt have the resources of the rich and landed. They were powerless to maintain their status in the new regime, though they had not been exploiters. In fact, many were liberal and welcomed the first steps to democracy; but they suffered as much as the upper classes and lost everything that had been so painfully acquired.

The life one had to live in those years bore no resemblance to anything one might call normal. A climate of tragedy and terror is unreal because it is unnatural. In ordinary life hunger, death, and fear are occasional traumas, absorbed into the daily fabric of existence. But when they become too large a part of life, the fabric of reality breaks down.

In the decade after 1917 in Russia, civil war, famine, and a brutal campaign of terror created such a climate. What a monk of Cluny wrote in 1040, at another of what historian Barbara Tuchman calls one of historys ebbs, would serve as an equally apt description nine centuries later: What can we think but that the whole human race, root and branch, is sliding willingly down again into the gulf of primeval chaos?

Cut off from their roots, material and spiritual, deprived of family ties and accustomed rituals, people lose their sense of self, and of their place in an ordered universe. They are cast adrift. Trying to remake a life is almost impossibly difficult without the comforting anchors of faith, family, and community.

Next page

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements