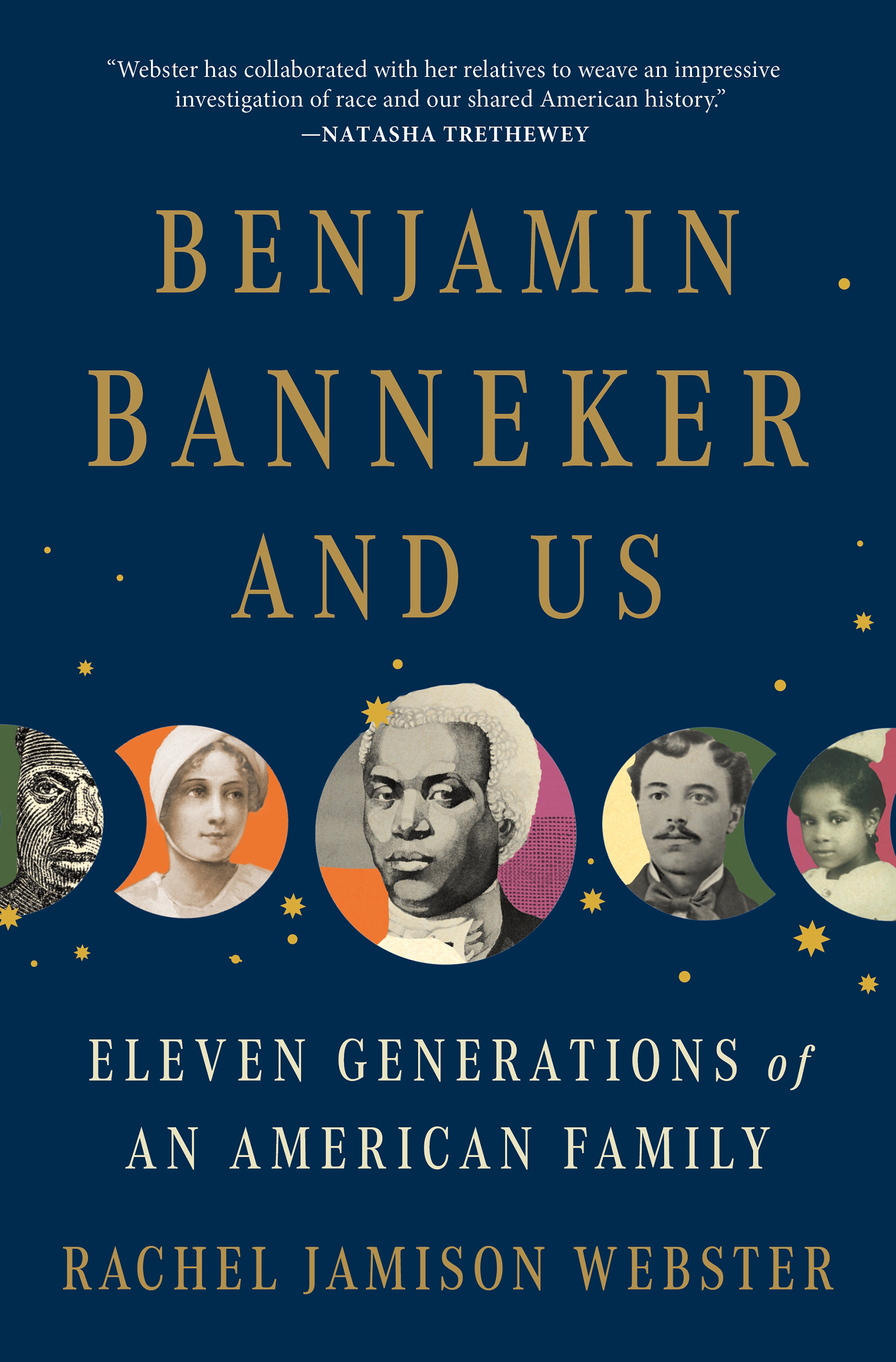

Rachel Jamison Webster - Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family

Here you can read online Rachel Jamison Webster - Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: Henry Holt and Co., genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family

- Author:

- Publisher:Henry Holt and Co.

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contrary to what you may have heard or learned, the past is not done, and it is not over. Its still in process, which is another way of saying that when its critiqued, analyzed, it yields new information about itself. The past is already changing as it is being reexamined, as it is being listened to for deeper resonances. Actually it can be more liberating than any imagined future if you are willing to identify its evasions, its distortions, its lies, and are willing to unleash its secrets.

Toni Morrison

We are in the middle of an immense metamorphosis here, a metamorphosis which will, it is devoutly to be hoped, rob us of our myths and give us our history.

James Baldwin

I wrote this book to explore a more honest version of my own ancestry, and a more honest version of American history. I have always been interested in the past and in the stories of my elders. But the idea of ancestry became more real to me in the last decade, as consumer DNA testing connected my family to genealogies and historical records that were previously unknown to us. As I write this, Ancestry.com has more than fifteen million members in its database, and 23andMe has more than twelve million members, and each of these members connects to thousands more ancestors and living relatives through those sites.

The collective, crowdsourced quality of this information demands a more collaborative approach to history. Knowing the names and birth dates of our ancestors also personalizes history and reveals that our ancestors were real, resilient, and imperfect, as we are. Learning about them and their lives can expose hidden injustices and ongoing denials. It can help us untangle what is the myth and what is the truth in our personal and collective stories. In my family, for instance, we lost track of our African American ancestry, in a denial that was mirrored in our wider nations denial of African presence and genius in its origin stories.

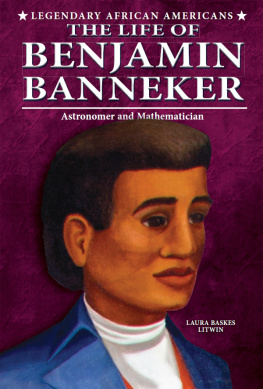

The ancestors I write about here include a dairymaid from England, a kidnapped and enslaved man from Senegambia, a multiracial family who sued their Ohio county in 1840 for their childrens right to a public education, and, most prominently, Benjamin Banneker. Banneker was a free person of color living in the Revolutionary era. He published the first almanacs by a Black man in the new United States, he helped to survey Washington, D.C., and he corresponded with Thomas Jefferson, calling out Jefferson on his hypocrisy as an enslaver who wrote about freedom.

As I learned about these ancestors, I knew that I wanted to write about them. But I did not know how to write about my Black ancestors ethically, as a white person. In creative nonfiction, aesthetic decisions are also ethical decisions, and to understand our ethical relationship with a work of writing, we must first examine our position of power and relationship to the story being told. Even though I was writing about my own forebears, I knew that I had to acknowledge the fact that my branch of the family passed as white several generations ago, losing track of these figures and failing our responsibility to our Black brethren. I decided that it was impossible for me to tell a story of Black genius and resistance without questioning my own position as a white woman and studying the origins and ramifications of whiteness itself.

Luckily, as I was in the throes of this internal debate, my Black cousins got in touch with me, and we began the collaborative sharing that became this book. My cousins kinship, generosity, and intelligence made this writing possible and allowed the book to find its proper form as a conversation between the present and the past, between our ancestors and ourselves. Our conversations represent a new integration in our family. They also embody a truth about ancestry. Ancestry is always a collective inheritance and not an individual one, and discovering our ancestry is as much about cultivating healthy relationships in the present as it is about unearthing the names of ancestors from the past.

In writing about these figures, I adhered to all the facts available to me. I read more than one hundred books and articles; I did research in the Maryland Archives, where our ancestors earliest records are located; and my cousins and I were given exclusive access to the archives at the Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum. We also studied Bannekers almanacs and manuscript journal, which are in the Special Collections of the Maryland Center for History and Culture. My cousins shared the oral histories that had been passed down through many generations of the Banneker-Lett family, and I was able to read the first oral histories that were recorded about Bannekers ancestry in the early nineteenth century. Finally, my cousins passed along their research to mephotographs, articles, wills, census records, and land deedsthat they had collected over the last forty years. These recorded histories provide the parameters for the books historical chapters.

But after researching the details and contexts of our ancestors lives, I allowed myself to imagine their thoughts and feelings, because I wanted them to live on the page as more than just names and dates. We need our imaginations to feel with one another, to heal our hierarchical relationships, and to experience both the specificity and the commonality of our humanity. This work of grounded imagination becomes most important, even necessary, when we are writing about people of color, women, and other marginalized members of society, because they are largely absent from historical documents. Most Black Americans were only recorded as people beginning in the 1870 census. And even those who were fortunate enough to be noted in the historical recordlike Benjamin Bannekerwere not given the same respect as white figures. I had only one of Bannekers journals to quote from, for example, because his other writings were lost when his cabin was set on fire on the day of his funeral. These all too common acts of violence are another reason why we have far less documentation to access when we write about ancestors of color. And yet, as our familys meticulous research reveals, these stories can still be discovered.

This biography of Benjamin Banneker and his lineage is more than just a family story. It is also a grappling with our nations racialized history and racialized present. It was written for my ancestors, living relatives, and fellow Americans in an attempt at narrative reparation. As our country becomes more and more multiethnic, and as we continue to develop more complex notions of history and selfhood, I hope that these ancestors stories will help us to celebrate Black brilliance and female resistance, and will replace some of our falsehoods with our truths. I hope they will help us imagine a more humane and inclusive future for our children and grandchildren, and for their children and grandchildren.

Rachel Jamison Webster, Evanston, Illinois, 2022

Ellicotts Mills, Maryland, 1791

BENJAMIN BANNEKER TIPPED back his chair and rubbed his eyes. It had been a four-candle night. When his final candlestick guttered out, he set his quill in the inkpot. He stood up, but his feet had fallen asleep in the long hours of sitting, so he hobbled a bit on them, rocking from his toes to his heels.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family»

Look at similar books to Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.