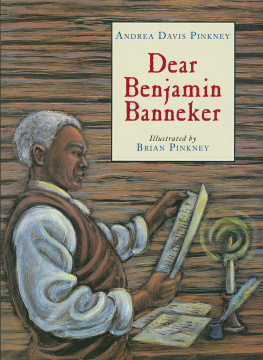

Text copyright 1994 by Andrea Davis Pinkney

Illustrations 1994 by Brian Pinkney

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The illustrations were prepared as scratchboard rendering, hand-colored with oil paint.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Pinkney, Andrea Davis

Dear Benjamin Banneker / Andrea Davis Pinkney ;

illustrated by Brian Pinkney

p. cm.

1. Banneker, Benjamin, 17311806Juvenile literature. 2. Almanacs, AmericanHistoryJuvenile literature.

[1. Banneker, Benjamin, 17311806. 2. Astronomers. 3. AlmanacsHistory. 4. Afro-AmericansBiography.] I. Pinkney, Brian, ill. II. Title.

QB143.B35P56 1994 520'.92dc20 93-31162 [B]

ISBN 978-0-15-200417-0 hardcover

ISBN 978-0-15-201892-4 paperback

eISBN 978-0-544-56567-8

v1.0115

Special thanks to Silvio A. Bedini for his extensive research and writing on the life of Benjamin Banneker. Also, appreciation goes to the Banneker-Douglass Museum and The Friends of Benjamin Banneker Historical Park for the preservation of Benjamin Bannekers legacy.

A. D. P. & B. P.

To my brother, P. J.

A. D. P.

To my mother and father

B. P.

Authors Note

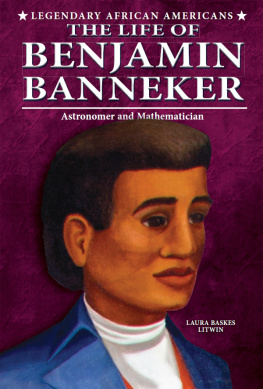

B ENJAMIN B ANNEKER was a self-taught mathematician and astronomer. Some folks say he was Americas first black man of science. But perhaps his most remarkable accomplishment was that he spoke out against racism long before civil rights became a large movement in America.

In his letter written to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson in August 1791, Benjamin attacked the institution of slavery and dared to call Jefferson a hypocrite. This correspondence helped establish Benjamin Banneker as a vital character on the stage of American history.

When Benjamin was a boy, his grandma Molly taught him to read and write. She used the Biblethe only book she ownedas a text. But Benjamin was most drawn to mathematics. While helping his parents work their tobacco farm, he practiced arithmetic by counting the steps needed to plant and harvest tobacco.

Along with mathematics, Benjamin was fascinated by machinery and how it worked. At the age of twenty-one, Benjamin built a wooden clock by duplicating the gears from a borrowed pocket watch. His handcrafted timepiece was rare in eighteenth century America. Most people back then told time by watching the position of the sun in the sky. Benjamins clock kept perfect time for more than fifty years.

For much of his adulthood Benjamin lived a quiet, humble life as a tobacco farmer. But in 1788, when Benjamin was fifty-seven years old, he began to teach himself astronomy.

Through his studies of astronomy, Benjamin learned to predict the weather. He even predicted an eclipse of the sun. An accomplished scientist, Benjamin used his skills to create an almanacsomething no black man had ever done before.

In January 1791, President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson hired Benjamin to help survey a new nations capital, which was later named Washington, D.C. Benjamin worked alongside Major Andrew Ellicott IV, one of the finest surveyors in the United States. Using the stars as his guide, Benjamin helped Ellicott lay the citys boundaries.

Like many trailblazers, Benjamin stood up for what he thought was right, and spoke out against what he believed to be wrong. It took almost 100 years for slaves to be granted their freedom from the time Benjamin wrote to Thomas Jefferson, voicing his views on the injustices of slavery.

Yet Benjamin Banneker, one of the first black men in American history to correspond with a government official, was brave enough to challenge the secretary of state to live up to the ideal Jefferson promised when he wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776: life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for everyone.

A NDREA D AVIS P INKNEY

N O SLAVE MASTER ever ruled over Benjamin Banneker as he was growing up in Maryland along the Patapsco River. He was as free as the sky was wide, free to count the slugs that made their home on his parents tobacco farm, free to read, and to wonder: Why do the stars change their place in the sky from night to night? What makes the moon shine full, then, weeks later, disappear? How does the sun know to rise just before the day?

Benjamins mother, Mary, grew up a free woman. His daddy, Robert, a former slave, gained his freedom long before 1731 when Benjamin was born. Benjamin Banneker had official papers that spelled out his freedom.

But even as a free person, Benjamin had to work hard. When Benjamin grew to be a man, he discovered that to earn a decent living he had little choice but to tend to the tobacco farm his parents left him, a grassy hundred acres he called Stout.

Benjamin worked long hours to make sure his farm would yield healthy crops. After each harvest, Benjamin hauled hogshead bundles of tobacco to sell in town. The work was grueling and didnt leave him much time for finding the answers to his questions about the mysterious movements of the stars and cycles of the moon.

But over the course of many years, Benjamin managed to teach himself astronomy at night while everyone else slept.

There were many white scientists in Benjamins day who taught themselves astronomy and published their own almanacs. But it didnt occur to them that a black manfree or slavecould be smart enough to calculate the movements of the stars the way Benjamin did.

Benjamin wanted to prove folks wrong. He knew that he could make an almanac as good as any white scientists. Even if it meant he would have to stay awake most nights to do it, Benjamin was determined to create an almanac that would be the first of its kind.

In colonial times, most families in America owned an almanac. To some, it was as important as the Bible. Folks read almanacs to find out when the sun and moon would rise and set, when eclipses would occur, and how the weather would change from season to season. Farmers read their almanacs so they would know when to seed their soil, when to plow, and when they could expect rain to water their crops.

Beginning in 1789, Benjamin spent close to a year observing the sky every night, unraveling its mysteries. He plotted the cycles of the moon and made careful notes.

The winter of 1790 was coming. In order to get his almanac printed in time for the new year, Benjamin needed to find a publisher quickly. He sent his calculations off to William Goddard, one of the most well-known printers in Baltimore. William Goddard sent word that he wasnt interested in publishing Benjamins manuscript. Benjamin received the same reply from John Hayes, a newspaper publisher.

Next page