Benjamin Bannekers Intellectual Powers

Benjamin Banneker, born in 1731, was a man ahead of his time. As a free African American in a time of slavery, Banneker was not welcome in white society, and he spent most of his life on his Maryland farm. There he harnessed his keen and curious intellect to teach himself complex mathematics and astronomy. Banneker secured a place in history with many accomplishments, including his role in surveying the site that became Washington, D.C., and his published almanacs with precise tide calculations and weather predictions. Banneker's accomplishments were used by abolitionists as proof of the intellectual powers of his race, and Banneker himself was one of the first African Americans to speak out against slavery. His correspondence with Thomas Jefferson has become famous.

Best books for Junior High and High School Readers (2000)

Science Books & Films

This is an excellent biography for a number of reasons.

Appraisal magazine

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Baskes Litwin grew up outside Chicago and studied history at Cornell University before becoming a freelance writer.

Image Credit: Library of Congress,

Benjamin Banneker's accomplishments were cited by abolitionists as an example of the intellectual abilities of his race. Banneker himself was one of the first African Americans to speak out against slavery.

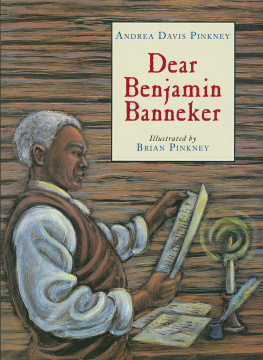

Benjamin Banneker was leaving home for the first time in his life. Although he was fifty-nine years old, Banneker had never before traveled more than a few miles from his small tobacco farm near the Patapsco River in rural Baltimore County, Maryland. It was early winter, in the year 1791, and the reason for Bannekers trip was an exciting one. Benjamin Banneker, a free black man, was going to help survey the land that would become the capital city of the young United States.

Surveyors measure an area and draw a map of its borders. In the eighteenth century, surveying could not be done without a thorough understanding of astronomy: The position of the stars was used to determine locations on the ground. Banneker had not had much formal schooling, but he was skilled in astronomy.

The Federal Territory, as the land to be surveyed was called, looked nothing like the city of Washington, D.C., today. The land that Benjamin Banneker was going to help map was still a marshy wilderness. Hidden by forest and murky swamps, it was the habitat of panthers, wild turkeys, and wolves. The Powhatan and Algonquin Indian tribes had lived there too, not so very long before.

Now the new Congress of the United States needed a permanent home in a central location on the seacoast. So, in the year before, the states of Virginia and Maryland had each agreed to give up an adjoining piece of this rugged land to be used for the capital city.

President George Washington, trained as a surveyor himself, chose the exact ten-mile-square area for the site. Then he chose the foremost surveyor of the time to direct the work: Major Andrew Ellicott IV.

Andrew Ellicott had drawn many of the new boundary lines in the young republic. Few people shared his skills in surveying. Yet this was not a job he could do alone. Major Ellicotts cousin George Ellicott suggested that his neighbor Benjamin Banneker might make a worthy assistant.

Although Andrew Ellicott had never met Benjamin Banneker, he had reviewed some of Bannekers astronomical calculations and knew he was a man with impressive scientific and mathematical abilities. Banneker had taught himself astronomy, beginning his study only two years earlier, at the age of fifty-seven, using borrowed textbooks and a borrowed telescope. He spent long nights making detailed observations of the stars. Alone, he had mastered the complex mathematical problems required to do astronomy. To have accomplished so much learning in so short a time, Banneker showed keen intelligence and great determination.

Andrew Ellicott hired Banneker as his scientific assistant for the survey, and the two men set out on horseback in early February for Alexandria, Virginia. This was the city nearest the territory they were to chart. For Banneker, who had never visited a large city before, the bustling activity on the wharves of the Alexandria seaport was strange and thrilling.

At that time, great ships filled the port, bringing dry goods from England and returning with furs and tobacco from America. Sailors, merchants, travelers, and city residents filled the streets. The sweet aroma of mince pies and pumpkin bread, floating from open bakery windows, contrasted sharply with the strong odor of oysters and cod hawked by fishmongers across the street. Several taverns, or ordinarys, as the locals called them, served tempting food and drink.

The surveying team could not tarry long, however; the men had an important job to do just outside town. On a high ridge in the forest, they set up a large observation tent with a hole cut in the top for the main telescope, or zenith sector, as it was called. This telescope was aimed straight up and was used to observe stars passing overhead.

As the earth rotates, stars appear above points on the earth on a predictable schedule. By knowing the exact location of the stars and the exact time of night, a surveyor can figure out the precise latitude and longitude of where he is standing. The surveyor takes many readings, then uses mathematics to compute the boundaries of the land being mapped.

Benjamin Banneker was responsible for maintaining an instrument called an astronomical clock. He closely monitored the sensitive clocks rate and temperature. Even the slightest movement or change in temperature could cause an inaccurate reading. This task required extreme concentration and diligence.

Although the cold winter months were best for stargazing, they were toughest for living in a tent. The hard ground and the frigid damp air made sleeping conditions miserable. Whats more, Banneker could sleep for only a few hours each afternoon. His work required long nights watching the bright stars. Such labor would have been demanding even for a man half his age. Yet Banneker did not stop working until the four straight sides of President Washingtons ten-mile square had been drawn.

Banneker was an able assistant to Andrew Ellicott in the survey of the Federal Territory. His careful note-taking and skill with scientific instruments helped the surveyor in this important project. That these methods were self-taught by a free black man in a time of slavery made them all the more remarkable. This was a time in which many people believed that a black mans intellect was inferior to that of a white mans. In mid-March 1791, the Georgetown Weekly Ledger filed this report:

Some time last month arrived in this town Mr. Andrew Ellicot [sic], a gentleman of superior astronomical abilities. He was employed by the President of the United States of America, to lay off a tract of land, ten miles square, on the Potowmack, for the use of Congress;is now engaged in this business, and hopes soon to accomplish the object of his mission. He is attended by Benjamin Banniker, an Ethiopian, whose abilities, as a surveyor, and an astronomer, clearly prove that Mr. Jeffersons concluding that race of men were void of mental endowments, was without foundation.

Only five months later, Benjamin Banneker would write a letter to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson in which he would respectfully question Jeffersons views regarding race and slavery. Before the years end, Banneker would write and have published the first of six famous almanacs and emerge as one of the countrys foremost amateur astronomers. After nearly sixty years of solitude, Benjamin Banneker would spend his next decade making history.