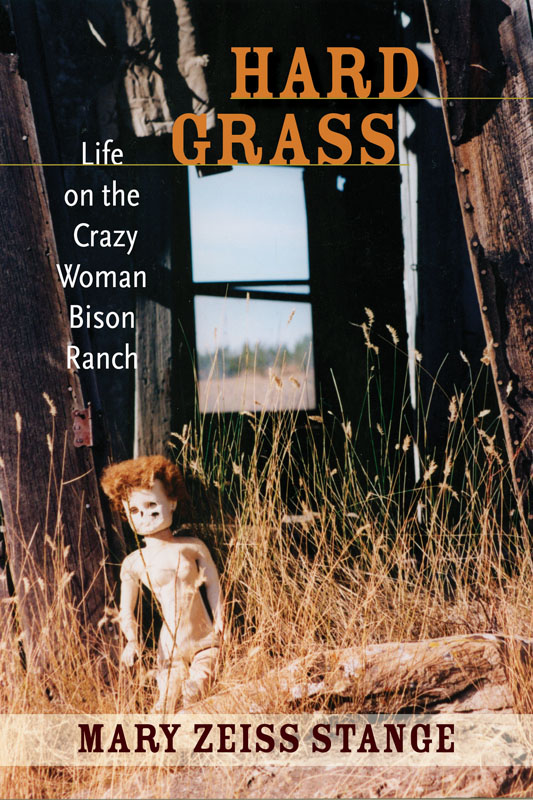

Hard Grass

Life on the Crazy Woman Bison Ranch

Mary Zeiss Stange

University of New Mexico Press

Albuquerque

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8263-4615-5

2010 by Mary Zeiss Stange

All rights reserved. Published 2010

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stange, Mary Zeiss.

Hard grass : life on the Crazy Woman Bison Ranch / Mary Zeiss Stange.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8263-4613-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Women ranchersMontanaBiography. 2. RanchersMontanaBiography. 3. Crazy Woman Bison Ranch (Mont.) 4. Bison farmingMontana. I. Title.

SF194.S78A3 2010

636.01092dc22

2010008316

Portions of the Introduction originally appeared, in different form, in Coming Home to the Country in High Country News (December 6, 1999).

A portion of Chapter 6 appeared, in different forms, in Homestead Hunting, Big Sky Journal (Fall 2001), and The Home Place, in Thomas McIntyre, Ed., Wild and Fair: Tales of Hunting Big Game in North America (Long Beach, CA: Safari Press, 2008).

A portion of Chapter 6 appeared, in different form, in Living with the ghosts of the Indian Wars, High Country News (February 6, 2006).

Portions of Chapter 7 originally appeared in an essay that won a First Prize in Sierra Clubs Why I Hunt essay competition in June 2006.

A portion of Chapter 12 was originally published in different form under the title New West code for city folk: No whining, USA Today (March 31, 2004).

Preface:

Working Off the Place

Most farm and ranch wives have to work off the place, to help make ends meet. This is one way to describe my situation. I simply work farther off the place than most.

It is a stark and simple fact of rural life that the majority of ranch operations do not generate sufficient regular, reliable income to sustain a family, let alone provide perks, like health insurance. So the women take jobs in town: as teachers or bank tellers or waitresses, working behind the counter in the grocery store, or pushing papers for the farm services agency. Such jobs produce a dependable supply of cash, to pay some bills and forestall having to make tough financial calls, like whether to put food on the table or a new sickle bar on the tractor mower, or whether to take ones daughter to the dentist or ones ailing Angus bull to the vet. Of course, for many of these women, as for their urban counterparts, work outside the home is as much a matter of choice as of necessity; they do it because they want to, and not merely because they have to. And most of them, again like their more citified sisters, can expect to work a second shift when they get back home. In the case of ranch wives, this means not only getting caught up on household chores like cooking supper and doing the dishes, but also anything from helping with the combining until well after sunset to staying up all night in a cold barn during lambing season. And then there are the myriad of practical decisions, large and small, that preoccupy a ranchers time and mental space.

So it is by no means unusual either that I have a day job off our ranch, or that a hefty proportion of my physical and emotional energy is channeled in the direction of day-to-day ranch matters. Its just that my town job, as a professor of womens studies and religion at a liberal arts college in upstate New York, is two thousand miles away from our remote southeastern Montana bison ranch. The long commute is possible, thanks to a flexible teaching schedule, generous vacation periods, mostly understanding colleagues, and the occasional extended respite of sabbatical time off for good behavior. These factors, plus a relationship in which my husband and I mutually pledged, twenty-seven years ago, that this marriagethe second for each or us, and we intended to get things right this timewould be based upon freeing each other to be and to do whatever it was that made us more authentically ourselves. For Doug, this eventually meant forsaking academe for the life of a full-time rancher. I held on to my day job, for a complex variety of reasons to be sure, but not least among them economic.

And so, I oscillate between two quite different worlds, my heart in one, my paycheck in the other, my head invariably in both. Friends and acquaintances in each setting seem to harbor private suspicions that I actually inhabit two different planets, and sometimes I think they may be right. This is perhaps especially true when those worlds collide: My office phone rings. Ranch business cannot always wait for evenings and weekends, let alone until my next trip home. It might be a relatively minor, yet nonetheless vexing, matter on which Doug needs a second opinionthings ranging from how best to fill out arcane government forms to which supplier we should contract with for custom bison feed. Then again, it could be a downright emergency, most of which have to do with large animals, heavy machinery, or some unfortunate combination thereof. There have been a few occasions on which I discovered, after the fact, how close I had come to becoming a widow. The call might, of course, also bring good news: of the births of healthy animals, of bad weather that didnt come or good weather that did, say, in the form of a desperately needed downpour. More recently, the less pressing mattersgood and badhave been relegated to e-mail, where they nestle among memos announcing campus-wide events and student requests for extensions on term papers. Meanwhile, considerations of how best to deal with a burgeoning prairie dog population in our west pasture cozy up to notes I am making on reproductive rights issues for tomorrows Intro. to Womens Studies class.

Over the years I have had to become fairly adept, then, at occupying two different mental spaces more or less simultaneously, just as I do two time zones, Mountain and Eastern. Transiting from one conceptual terrain to the other is not infrequently a bumpy ride. But what might strike the casual observer as a jarring juxtaposition of radically different sets of information and their accompanying emotional states is, necessarily, just day-to-day living for me.

As to the physical commute: A mere few in-flight hours can separate my attending a faculty wine and cheese reception (this being Dougs favorite fantasy of how I spend my time at school) and struggling with a pipe wrench, sweat-drenched and up to my elbows in rusty muck, in the process of helping to pull a pump from a stock wella two-person job that had awaited this particular trip home (and during which I mutter, If the folks at Skidmore College could see me now ). The gauzy Western-inspired Ralph Lauren skirt and Italian sandals I wore to that reception would not survive a single stroll across our hard-grass hayfield. Indeed, my ranch wardrobe doesnt even contain a skirt. I dont bother to paint my fingernails when Im home, since the polish wouldnt outlast a days work. I accessorize with the cuts, bruises, insect bites, and minor abrasions that invariably come with a days work.

Yet in other ways these worlds I inhabit are not so distinct. Early on in our tenure on the ranch, the day before my departure to begin the school year, Doug and I met with Bureau of Land Management agents to work out a rotational grazing plan for our place. A week later and two-thirds of a continent away at Skidmore, I was sitting on the Committee on Educational Planning and Policy designing an improved all-college curriculum. Only the details differed; from a bureaucratic point of view, the two meetings were essentially a trade-off. More recently I have noted the structural likenesses between the pecking order of a buffalo herd and power arrangements on a college campus. As to the resemblance of year-end grading to mucking out paddocks well, you get the idea.