Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

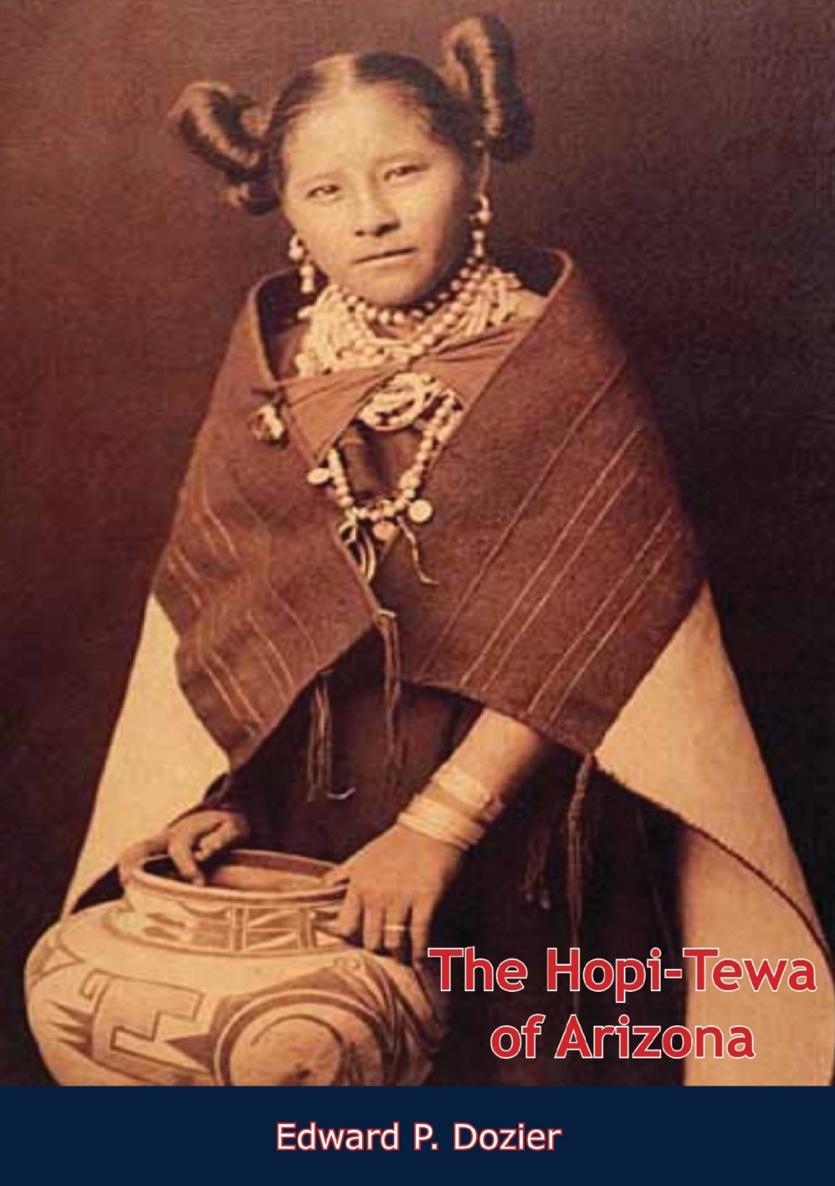

THE HOPI-TEWA OF ARIZONA

BY

EDWARD P. DOZIER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THE FIELD WORK for this study was financed by a predoctoral fellowship from the Social Science Research Council and a John Hay Whitney Foundation fellowship. A postdoctoral grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research made possible the preparation of this monograph for publication. To all these foundations I wish to express my thanks and appreciation.

The initial field study was made under the sponsorship of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology of the University of California at Los Angeles. I am particularly grateful to Dr. Ralph Beals, Dr. Walter Goldschmidt, and Dr. Harry Hoijer of that department for constant aid and advice in the course of my field work and the preparation of this manuscript.

I am indebted to a number of institutions for the services extended to me in the course of my field research and the work on this manuscript. The personnel in the Departments of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, New Mexico, and Oregon generously made available their help and facilities. The Museum of Northern Arizona, at Flagstaff, was extremely helpful, and I am happy to extend my appreciation to its staff. Dr. Harold S. Colton of that museum generously made available his excellent personal library on the Southwest for my research. My grateful thanks are communicated to him.

In particular, for encouragement and for many suggestions, I wish to express my thanks to Drs. Florence Hawley Ellis, W. W. Hill, and Leslie Spier of the Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico.

Dr. Fred Eggan placed at my disposal in the beginning of my research a copy of his then unpublished chapter on Hano Social Organization, which proved to be exceedingly helpful. For this and other information he supplied from time to time in the course of my study I wish to express my sincere appreciation.

For their reading of the whole or parts of the manuscript and for offering many fruitful suggestions I am thankful to Dr. and Mrs. John Adair, Cornell University; Mr. and Mrs. Robert Agger, University of Oregon; Dr. George Barker, University of California, Los Angeles; Mr. and Mrs. John Connelley, Shongopovi Day School, Hopi Reservation; Mr. Oliver La Farge, president of the Association on American Indian Affairs; Mr. Robert Sheward, University of Arizona; Mr. Watson Smith, Peabody Museum, Harvard University; and Dr. and Mrs. Edward H. Spicer, University of Arizona.

For help with charts and drawings I am indebted to Mr. Thomas Bahti, Desert House, Tucson, Arizona, and Mr. Milton Snow, Navaho Field Service, Window Rock, Arizona.

I also deeply appreciate the assistance given by my wife, Marianne Fink Dozier, in the field work and in typing and copy reading my manuscript.

Finally, but not least in importance, I wish to express my thanks and appreciation to my many Hopi and Hopi-Tewa friends without whom this study could not, of course, have been made. To one family in particular, who I am sure would prefer to go unnamed, I wish to express my thanks. This family provided a home and a host of relatives whom I am honored in the Hopi-Tewa manner to claim as my own.

INTRODUCTION

TEWA VILLAGE, {1} the Tewa-speaking community in northern Arizona, is the easternmost pueblo on the Hopi Reservation. It is one of three pueblos on First Mesa; the other two communities are Shoshonean Hopi in speech and culture. Although the inhabitants of Tewa Village speak another language and are set off culturally from the Hopi people, nothing about the outward appearance of the pueblo suggests this separatist quality. Tewa Village, in village plan, in architectural features of the houses, and in dress and material possessions of its inhabitants, appears to be a typical Hopi pueblo. Even in the physical appearance of the Hopi-Tewa no difference between them and the Hopi is apparent. Both belong to a fairly homogenous puebloid physical type. Culturally, however, the two peoples are quite distinct. The analysis of their differences is the main concern of this study.

Although abundant literature exists on the Hopi, there is very little information regarding the Hopi-Tewa. Since Tewa Village is a comparatively recent community and its culture is manifestly different from that of the Hopi, those interested in the more colorful and ceremonially richer Hopi culture have bypassed it. The Hopi-Tewa, however, are an important group in themselves, and a study of them is needed. Moreover, they represent a group in which studies of social and cultural change promise fruitful returns. Freire-Marreco (1914) and Parsons (1936 a , pp. xliv-xlv) realized the importance of such a study of the Hopi-Tewa, and recently Eggan (1950, p. 175) has reaffirmed this importance. Virtually all that we know of the Hopi-Tewa comes from fragmentary accounts made by investigators preoccupied with a study of the Shoshonean-speaking Hopi. Eggan has summarized this information in exemplary fashion in his recent book (1950, pp. 139-175) and has raised many problems for further investigation.

This study investigates some of the problems of the Hopi-Tewa. It is first of all a study of the distinctive elements of their culture. It is concerned with the history of these people, and particularly with the social mechanism by which they have preserved their identity during three centuries of close association not only with the Hopi on First Mesa but also with the Spanish and the Anglo-Americans.

The ancestors of the Hopi-Tewa can be traced with assurance over a period of 650 years. Struggles against nomadic tribes, droughts, smallpox epidemics, and Spanish oppression characterized the history of the group before they left their homeland in New Mexico and settled with the Hopi more than 250 years ago. The Hopi-Tewa were a refugee group escaping from Spanish oppression. Legends, myths, and information supplied by Hopi and Hopi-Tewa informants also indicate that they were in a minority status at Hopi for a very long time. In this new homeland they clung tenaciously to their own cultural forms and effectively resisted acculturation with their neighbors. It is interesting, however, to note that, although pronounced differences still exist between the two groups, resistance to acculturation has declined sharply since the beginning of the century. At the present time it appears that the two groups are actually merging and that the antagonisms have for the most part subsided. {2} The change took place coincident with accelerated American activities, such as the establishment of the agency and of government schools, the dissemination of stock-raising information, trading-post activities, the employment of Indians for wage work, and the influx of tourists.