It is true when they say the moment a child is born, the mother is also born. Motherhood and being an immigrant woman of certain age is an interesting mix, I concluded.

I was born and raised in Seoul, Korea and came to London alone in 2000. As a young girl a few months shy of turning twenty, I had left a home that I never really felt I belonged to and was eager to dive deep into my newfound freedom and immerse myself fully in London life. I didnt want to be recognized as a foreigner; I desperately wanted to be accepted by the city I had fallen madly in love with. Twenty-two years on, I call London my home, I am married to an English guy I met in a pub eighteen years ago, and now raise a child of dual heritage who looks and acts exactly half like me and half like her father.

But the birth of my daughter in 2015 left me feeling deeply lonely and homesick. Having spent all my adult life in the UK, motherhood made me feel confused about my identity as an immigrant and a mother. I was a Korean living in London, but when I went back home I was also a foreigner visiting Korea. Twenty-two years of being so far away, with very few visits in between and even fewer interactions with anyone who even remotely reminded me of home, had been enough to make me naturally drift away and lose a lot of what made me Korean. Gosh, was I that desperate to integrate? Even at the cost of losing my own sense of identity?

After so many years of living in London, to be faced with the truth that I neither felt Korean nor British was a difficult moment for me. Beyond that, the stark realization that I, as an immigrant mother, bore the sole duty to pass on the culture of my Korean heritage to my daughter hit me hard and weighed heavily on my heart, raising some fundamental questions.

I wanted to tell her the stories of where I come from and why I am here. I wanted us to cook the kind of food my mother fed me as a child and taste my childhood together. I wanted to speak the language my mother spoke and whisper our secrets to each other in the most intimate and loving ways I remember sharing with my own mother as a child.

But truth be told, everything felt like a real effort all very alien and almost unnatural.

I really wanted my daughter to feel connected to my home, my family and where I come from. But so much of my own heritage and Koreanness had been lost in the name of integration, including the comfort of my own mother tongue. It felt so strange to speak to my daughter in Korean, it often made me feel ashamed.

How was I supposed to tell my child what the other half of her blood is made of if I was unsure of who I am as a mother?

I missed the connection and familiarity of the land I was born and raised in; the soil I walked on, the culture and the people. I was so far removed from it all that I felt a deep void. So, to satisfy that longing, I started to cook the dishes I remembered from my childhood. I read and researched, and felt comforted by the tiny nuances I picked up between the lines. Then I got hungry for more. I dug deeper into the memories, craving that last taste of something I had eaten, desperate for some kind of connection, the warm embrace of something familiar. The perpetual cycle of hunger haunted me as I yearned for a sense of belonging.

It was becoming a mother that had made me realize the importance of continuing to cook dishes that connect me deeply to my roots, allowing me to restore my sense of a Korean heritage. After all, it is my daughters birthright, and it is my duty to share the recipes from my family and traditions, ensuring she is entirely familiar with them and rooted in both sides of the cultures she has inherited.

My fathers phrase, A family that eats together stays together, held great meaning for me throughout this personal journey, in both physical and metaphorical terms. Cooking and sharing the food of my origins the dishes of my childhood homes and memories truly helped me to reconnect to my long-forgotten Korean home.

Food allows us to remember and celebrate our inherent roots and feel a sense of belonging, however far we may be from home. And this is my story of reconnecting to my Korean roots. Its also a love letter to my daughter spoken through the dishes of my childhood that I cook in my tiny London kitchen where love is spoken tenderly through the memories of taste.

Our family kitchen of two halves and our love for food has reshaped and redefined what Korean food means to us. Food is the language of love my family chose, both here and back home in Korea. It is the language I choose to love my daughter the Korean way, because it is the only language that I speak fluently.

I really hope you will find your own stories in here somewhere and feel comforted in knowing that we all belong here.

Su x

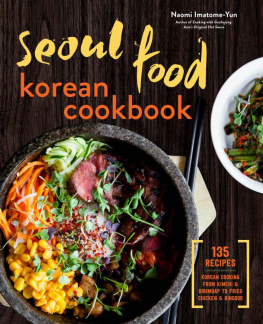

I believe cooking is about accessibility, and I try to keep things simple at home. It is helpful that the popularity of Korean food has steadily grown more mainstream over recent years and sourcing Korean ingredients has become a lot easier for most of us. I hope these few notes will fill in any gaps in your knowledge about the ingredients and their uses.

There arent many unusual ingredients. Though a couple of items are unique to the Korean larder and therefore trickier to find suitable substitution for, but they can easily be found in Korean or Asian grocers and online.

There is a common misconception that Korean cooking is difficult, but I think when we talk about particular cuisines being difficult, it often simply reflects a lack of familiarity. Once we understand the basics, and how the predominant flavours impact and influence one another, we can start building the characteristically robust Korean flavour profiles with confidence.

Typically, the flavours of most Korean dishes can be built around what we call gazn-yangnyeom , which loosely translates as a balanced assorted seasoning. It broadly consists of a mixture of spring onion (scallion), garlic, toasted sesame seeds/oil, sugar and salt. These are combined with one or more of the trio of Korean fermented jang ganjang , soy sauce; doenjang , fermented bean paste; and gochujang , fermented chilli paste to give the dish the desired depth and finish. It really is as simple as a few aromatics combined with an element or two of fermented seasoning.

On English + Korean Names

Losing the ability to speak my mother tongue fluently has been one of the main contributing factors that made me question my identity. I couldnt grasp the language of my birth well enough and felt uncomfortable using it even with my daughter.

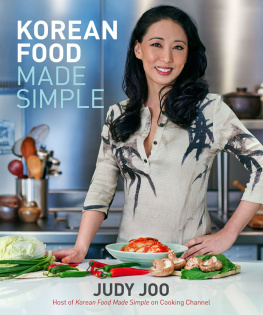

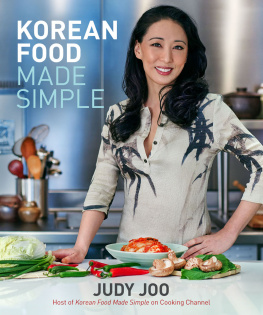

Food and stories calling upon my taste memories have been the only medium that I relied on to share with my daughter the wealth of Korean culture I knew. When I came to write this book, it was therefore beyond important to me to strike the balance between the languages, to use them not to alienate the reader as they had sometimes made me feel alienated from my Korean culture but to open doors to understanding.

I have therefore included Korean names for each of the recipes, as I wanted the dishes to have the provenance of their origins, to have the roots which are either Korean dishes that I grew up eating or that trace back to the traditional meals that have directly influenced the recipes I have developed for the book. And I wanted the readers, including my daughter, to be able to look up the dishes online for what they are, to extend their exploration.

Next page