Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2018 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8131-7469-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7471-6 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7470-9 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

STARTERS

The Role of Food in Bereavement and Memorialization

Cooking and Corpses

The idea for this book emerged from the intersection of an interest in food from a personal perspective and an academic focus on the role of food in death and ritual practices. In modern society, food, life, and death have developed a rather precarious relationship with one another, as food consumption, class status, and notions of health are rapidly shifting, globalization is changing and increasing our food choices, and society is becoming more multicultural. Both death and food, in their rapidly changing states, must be examined and studied. The definition of death is not universalsome cultures see it as a process, others as a single moment. Some cultures view cardiopulmonary failure as death, whereas other cultures use brain death as their standard to define when death occurs. Similarly, food and foodways are not by any means universal. Food, like birth and death, has the ability to frame time, shape our days and the way in which we view and construct time, and regulate human experience. Through food, and the meal, social networks are formed and time is regulated.

Preparation of food is also important, as cooking is transformational: it is what turns food from mere sustenance into communal and social rituals. As Fernndez-Armesto writes, Everywhere, eating is a culturally transformingsometimes a magically transformingact. It has its own alchemy. It transmutes individuals into society and sickness into health.1 The act of preparing food, followed by the act of consuming it, is similar in this way to the way death decays our bodies. We prepare dead bodies for public consumption, through washing, purifying, embalming, or cremating them, preparing bodies to participate as corpses (or even as absent bodies) in public and social rituals of bereavement and loss. Similarly, we transform food into meals, preparing and altering food in the kitchen, changing raw materials into a synergetic meal. Cooking and corpses both transform and construct social rituals in which we come together and think about life, death, and life after loss; food is a mediating agent between heaven and earth and life and death.2

Death and Food: An Introduction

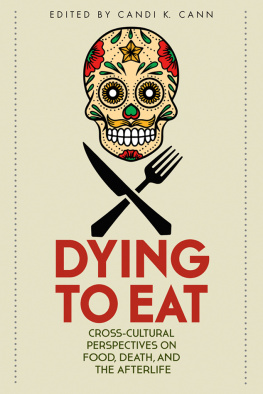

With some exceptions, studies conducted on food and death generally fall into one of the following categories: (1) food as a direct causation in preventing, prolonging, or causing death;3 (2) food scarcity or abundance and its role in economic development or colonization (eco-critical studies of creating or preventing death);4 (3) feasts and fasts and their relationships to saints, martyrs, and the general role of food (or absence of food) in religious asceticism and practices;5 (4) explorations of dietary restrictions or food symbolism in religious texts and practices;6 (5) anthropological and sociological explorations of food and foodways as a form of cultural identity;7 and (6) food as a gender marker, in relationship to marginalized discourse and power.8Dying to Eat seeks to contribute to these various studies of the relationship between food and death by offering an interdisciplinary approach to the intersection of food and death, using a variety of disciplinary approaches, ranging from anthropological to religious to eco-critical, and arguing that the tensions between food and death are perhaps best explored through this interdisciplinary approach.

In recent years, popular literature and social media regarding food and death have placed food and death at center stage, as iconoclastic chefs herald their favorite meals in such books as the recent best seller My Last Supper, a coffee-table book rich with recipes, photographs, and stimulating conversation regarding what the last meal in life should bea resplendent meal inducing a sensory experience, or comfort food that evokes ones childhood home. My Last Supper has an online website, a blog, and a continually growing audience, appealing to self-declared foodies and gourmet chefs alike and focusing on food as the main subject, where chefs highlight the role food has played in their lives.9 Death in this book operates as a framing mechanism to allow food to play a central role in life and its meaning; food is presented as nourishing not only in substance but also in significance. Internet memes offer a similar focus on the last meal, but from a more sinister and depressing point of view, in the form of pictures of last meals requested by death-row inmates in various American prisons.10 Death and food intersect here as an unspoken (and largely unexplored) discourse on powerboth of the state over bodies that it nourishes, punishes, and then destroys, and of food, in its ability to evoke a sense of comfort, familiarity, and presence (through shared meals past). With these memes reaching several million Internet views and the book My Last Supper topping the New York Times best-seller list, it is evident that food plays an important and central role in contemporary society and culture.

Food is a central actor in funeral feasts, bereavement rituals, and memorialization practices, and it remains an enduring (and often overlooked) part of the material world of grief. Food has played a major role in funerary and ritualized funerary practices since the beginning of humankind. In the ancient Roman world, it was common practice to build tubes connecting the tops of the graves with the crypts themselves, and mourners would regularly pour food and drink offerings (mostly bread and wine) into these tubes, whose other end would be placed in the mouth of the corpse, in order to feed the dead while they waited for their afterlife. Similarly, early Christian mourners, remembering and honoring the dead, regularly feasted at graves, and it was common for cemeteries to contain kitchens to aid in the preparation of food for the graveside feasts that fed the dead while they waited for their resurrection.11 By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Christians in Great Britain commonly placed bread or cake on the corpse to absorb the sins of the deceased, to aid his or her journey to the afterlife. Some families even hired official sin eaters, who, in exchange for a small amount of money, would eat the sins of the dead in order to expunge them. These corpse cakes were gradually replaced by the popular and communally shared funeral biscuits of the Victorian era, which were wrapped with printed prayers and poems meant to comfort gathered mourners, rather than to intercede on behalf of the dead.12