DOVER CRAFT BOOKS

EGG DECORATION, Susan Byrd. (0-486-26804-7)

EASY-TO-MAKE BIRD FEEDERS FOR WOODWORKERS, Scott D. Campbell, (0-486-25847-5)

MAKING CHAIR SEATS FROM CANE, RUSH AND OTHER NATURAL MATERIALS, Ruth B. Comstock. (0-486-25693-6)

THE COMPLETE BOOK OF STENCILCRAFT, JoAnne Day. (0-486-25372-4)

THE SPLENDID ART OF DECORATING EGGS, Rosemary Disney. (0-486-25030-X)

BUILDING SHIP MODELS: PATTERNS AND INSTRUCTIONS FOR A CLIPPER SHIP AND A WHALER, George B. Douglas and Joseph T. Higgins, et al. (0-486-40215-0)

SHELL CRAFT, Virginie Fowler Elbert. (0-486-27730-5)

MARIONETTES, Helen Fling. (0-486-22909-2)

LEATHER TOOLING AND CARVING, Chris H. Groneman. (0-486-23061-9)

EASY-TO-MAKE CANDLES, Gary V. Guy. (0-486-23881-4)

THE JEWELRY ENGRAVERS MANUAL, R. Allen Hardy & John J. Bowman. (0-486-28154-X)

SILK PAINTING, Jill Kennedy & Jane Varrall. (Available in United States and Canada only.) (0-486-27909-X)

METALWORK FOR CRAFTSMAN, Emil F. Kronquist. (0-486-22789-8)

BASIC BOOKBINDING, A. W. Lewis. (0-486-20169-4)

THE COMPLETE BOOK OF PUPPETRY, George Latshaw (0-486-40952-X)

EASY-TO-MAKE WHIRLIGIGS, Anders S. Lunde, (0-486-28965-6)

MAKING ANIMATED WHIRLIGIGS, Anders S. Lunde (0-486-40049-2)

LIVING LIKE INDIANS: A TREASURY OF NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN CRAFTS, GAMES AND ACTIVITIES, Allan Macfarlan. (0-486-40671-7)

KNOTCRAFT, Allan & Paulette Macfarlan. (0-486-24515-2)

METALWORK AND ENAMELLING, Herbert Maryon. (0-486-22702-2)

How TO MAKE DRUMS, TOM-TOMS AND RATTLES, Bernard Mason. (0-486-21889-9)

ENGRAVING AND DECORATING GLASS, Barbara Norman. (0-486-25304-X)

FANTASY DESIGNS STAINED GLASS PATTERN BOOK Carolyn Relei (0-486-43299-8)

POTTERY FORM, Daniel Rhodes (0-486-43513-X)

HAND PUPPETS: HOW TO MAKE AND USE THEM, Laura Ross (0-486-26161-1)

THE COMPLETE CALLIGRAPHER, Frederick Wong. (0-486-40711-X)

Paperbound unless otherwise indicated. Available at your book dealer, online at www.doverpublications.com , or by writing to Dept. 23, Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, NY 11501. For current price information or for free catalogs (please indicate field of interest), write to Dover Publications or log on to www.doverpublications.com and see every Dover book in print. Each year Dover publishes over 500 books on fine art, music, crafts and needlework, antiques, languages, literature, childrens books, chess, cookery, nature, anthropology, science, mathematics, and other areas.

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

Copyright

Copyright 1986 by Aldren A. Watson.

All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1996, is an unaltered, unabridged republication of the work originally published by Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, in 1986.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Watson, Aldren Auld, 1917

Hand bookbinding, a manual of instruction / by Aldren A. Watson; illustrations by the author.

p. cm.

Includes index.

9780486132549

1. BookbindingHandbooks, manuals, etc. 2. HandicraftHandbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title.

Z271.W36 1996

686.302de20

95-52594

CIP

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

For Eva Mansfield Auld

and Cammie and Thomas

Table of Contents

Introduction

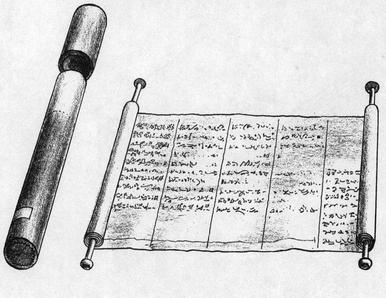

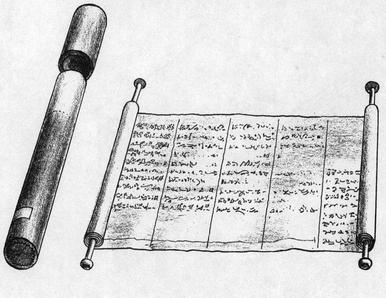

Paradoxically, the history of bookbinding begins many hundreds of years after the appearance of the first book, one of the earliest examples of which is an Egyptian papyrus roll composed of eighteen columns of hieratic writing, dating from the twenty-fifth century B.C. and stored in a tube binding (1). The roll form (from the Latin volumen, roll of writing) continued well into the Christian era, when parchment gradually replaced papyrus as a writing material. The arrangement of the writing in parallel columns separated by vertical lines held the potential for the development of an entirely new form. Eventually the idea of cutting the roll into a number of flat panels, each holding three or four columns, inspired a binding that was more convenient to use and that would prove to be more durable.

The first bound book was made up of single sheets hinged along one edge by means of lacing or sewing. In the Latin codex or manuscript book, the columnar arrangement was continued, with typical examples from Roman times having three or four columns to the page. Down to the present day, two- and three-column pages have been in common use, particularly in reference books and textbooks in which short lines contribute to easier reading. Partly for the sake of legibility, modern trade books are predominantly single column and consequently of a smaller trim size than books of earlier times.

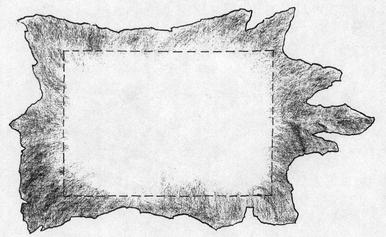

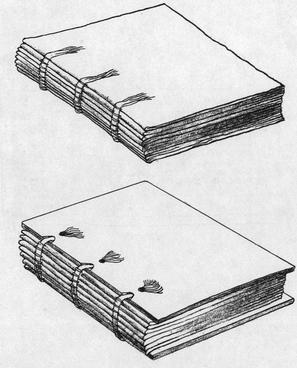

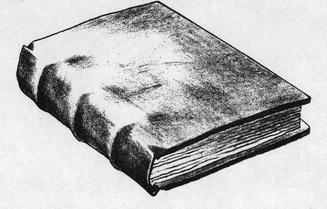

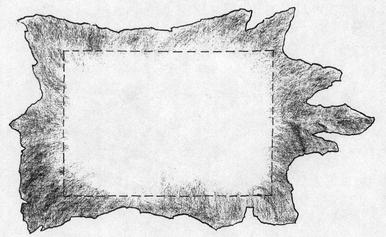

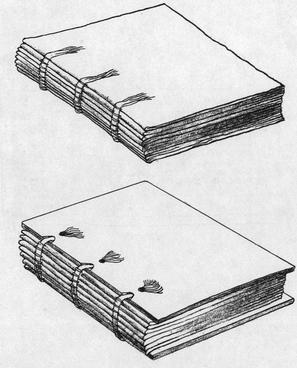

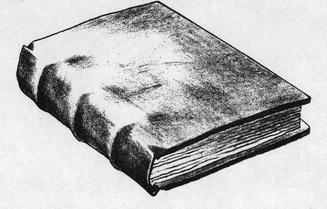

Early bindings exhibit all the basic construction elements that characterize modern bindings. They were made up of folded sheets collected into gatherings, or signatures, and sewn onto cords running across their backs. The pages of these books were large, probably much influenced by the size of the animal skins from which the parchment was made (2). Subsequently, wooden boards were placed on either side of the sewn signaturesbut not attached to themin positions corresponding to the front and back covers, to protect the books pages. At some later time it was discovered that the cords to which the signatures were sewn could as easily be laced directly into the edges of the boards to form a more compact and durable unit (3). The fundamental evolution of bookbinding was completed when the whole volume was covered with a sheet of leather to conceal the cords and sewing, to reinforce the hinges, and to provide protection and permanence (4).

The development of bookbinding is both simple and complex. In the past eighteen hundred years the basic construction of the book has not changed, as an examination of a contemporary binding will show. It is still a series of signatures sewn one to the other at the folds and secured between two boards whose outer surfaces are covered. Just as the perfection of any technique cannot proceed in isolation from other factors, bookbinding has been influenced by many events having nothing directly to do with books or even literature.

The early monastic orders were the guardians of nearly all knowledge in the Middle Ages, with respect to both writing and scholarship. Thus it is not surprising that the same persons to whom these skills were entrusted also assumed the role of bookbinders. Their craftsmanship reflected a thoroughness of education available to only a privileged minority. Hence the beginnings of bookbinding are associated with the church, with ecclesiastical history and literature, and with manuscript reference books.

The large size of early manuscript writing (5) was governed by the writing tool itself and demanded a generous page size, while the considerable thickness of the handmade paper was mostly what contributed to the bulk of the bound book. Letter by letter, each word, line, and page was patiently handwritten and usually enhanced with flourished initials illuminated in brilliant colors. The bindings were of leather, their large boards inviting decoration. There are countless examples with richly tooled designs combined with settings of gems, rare stones, and heavy gold leaf (6). As a further embellishment, engraved gold clasps or latches were attached to the boards to hold them closed. Working with good materials and virtually unlimited time, the monastery binders produced work of uncompromising quality and durability. These ceremonial reference books were quite literallythen as noworiginal works of art, intended for the use of only a select few people. Quite apart from their content and visual beauty, perhaps their greatest value lay in the impossibility of replacing them, for many of these limited editions would have been copied from equally unique volumes borrowed with difficulty from another library at a great distance. Needing to be carefully guarded, in the monastery library these rare books were hitched by chains to the shelves or reading tables.

Next page