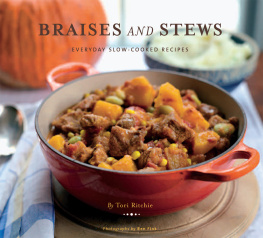

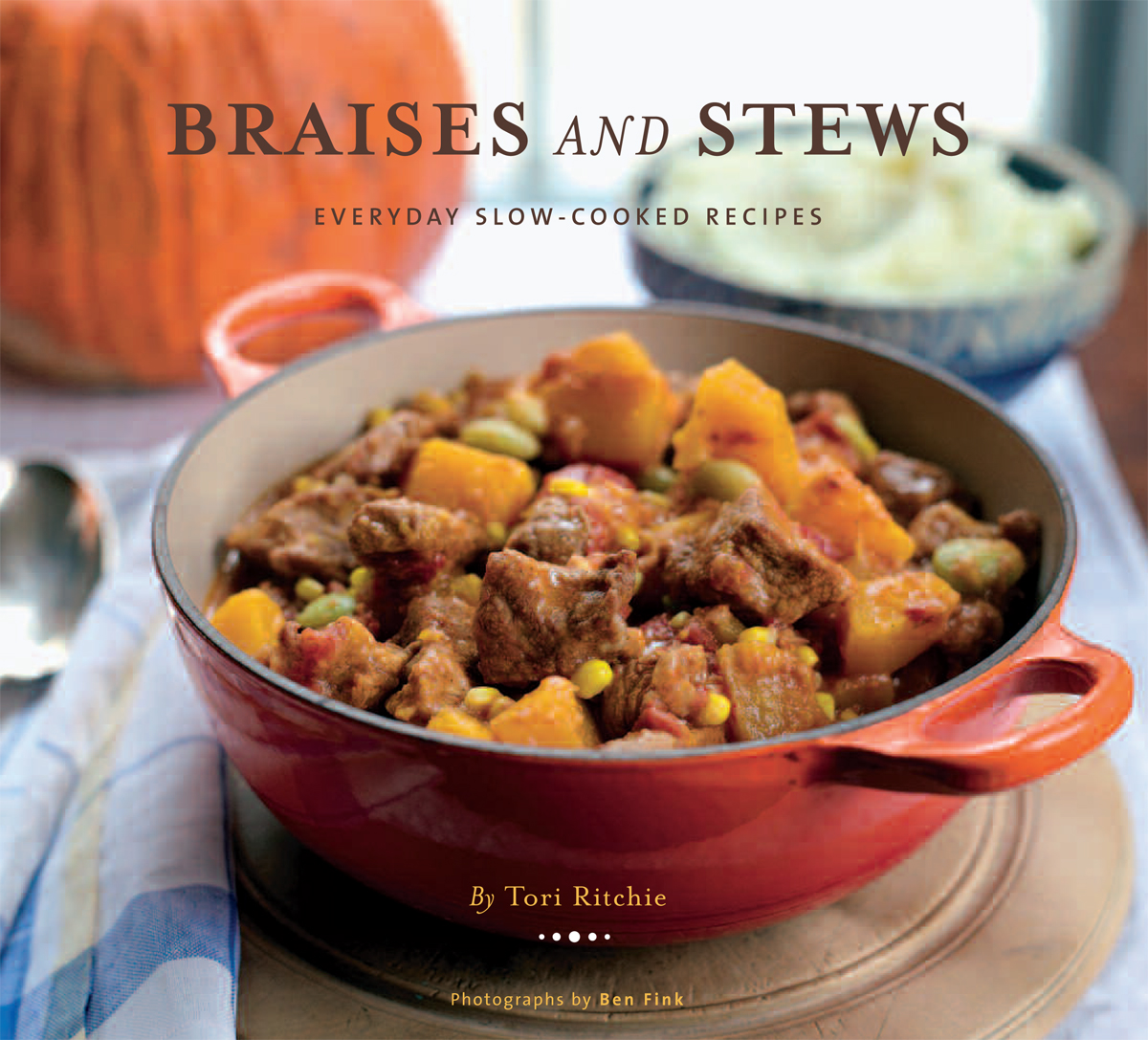

This book is dedicated to Sue Ritchie for raising me on pot roast and to San Francisco, my beloved hometown and the best place to test braising recipes all year;

To Leslie Jonath for her endless enthusiasm and love of braised cabbage, to Laurel Leigh for her unflappability, to Ann Martin Rolke for her careful and thoughtful editing, to photographer Ben Fink, food and prop stylist Melissa Hamilton, and designer Gretchen Scoble for making the pages beautiful;

To Amanda Haas, recipe tester, friend, and great company in the kitchen;

To Mary Risley for providing her kitchen, useful advice, and good humor;

To those who contributed recipe ideas and inspiration: Katherine Cobbs, Naneita Cobbs, Judy Custer, Vicky Kalish, Sara Whiteford, and Susan Herrmann Loomis;

To the Hunters, once again, for the pool house kitchen;

To my culinary gal pals, who keep me laughing and excited about what we do: Julie Hamilton, Katherine Cobbs, Donata Maggipinto, Sara Whiteford, Mary Barber, Bibby Gignilliat, Kelly Whalen, Diane Morgan, and Sara Deseran;

To Brooks-An Brazil for supplying great chile peppers from Santa Fe;

To Blaise: You know why you have to be in this book;

And, most of all to Sam Whiting, who eats everything.

A big yellow pot is on the stove, theres a warm fire underneath it, and an incredible scent fills the air: Theres pot roast for dinner and everyone is hanging around the kitchen. This is why we braise, because who can resist lifting the lid off that pot and dipping in to the tender meat, vegetables, and sauce below? Braising is primal. If, as its said, the first cooking method discovered was grilling, I have to believe the second was braising. Its also global. Italians will swoon over stracotto, their pot roast; the French have elevated braised fish to art with bouillabaisse; Mexican carnitas has fueled generations from the Yucatn to the Yukon; and Indian curries have influenced empires. Yet braising is uniquely local, too. Every cook seems to have a special recipe. Isnt your mothers (or grandmothers or uncles) brisket, chili, or rag the best youve ever had?

What makes braising relevant today is the reason its been around so long: Its time efficient, economical, alchemical. You can throw food in a pot and walk away for hours while inexpensive, tough cuts of meat and knobby vegetables are magically transformed into dinner. And even though these dishes are slow-cooked, that doesnt mean they take forever. Putting together a good braise rarely takes more than half an hour, then it needs little attention. Meat braises cook for a couple of hours, poultry takes as little as thirty-five minutes, and seafood and vegetable braises are often done in twenty minutes. Slow is relative; it depends on the type of food you are cooking, not on the clock. Stewing is braisings fraternal twinmade the same way, but with slightly different looks. A stew may have smaller pieces of food and a bit more liquid, but the technique is the same.

To survey all the braises and stews of the world would exceed what I want to do in this book. What I want to do is help you get a great dinner on the table tonight without searching for special ingredients, without exhaustive preparation, without spending a lot of money. These recipes are my favorites, culled from twenty years of loving to experiment with braising. This is everyday foodgood for family dinners, good for parties, good for you.

BRAISING BASICS

The word braising sounds more technical than it is. The method is very simple: Food is simmered in minimal liquid in a closed pot until the essence in every ingredient flavors every other ingredient. To do it, you have to have the right equipment; you have to know the basic steps; and you have to choose the right ingredients.

THE POT

It doesnt get any more fundamental than this: You need the right pot for braising. It has to be heavy enough for long cooking without scorching; it has to be large enough to hold multiple ingredients, but not so big that they swim around; it has to have a tight-fitting lid so the food can baste over and over in its own juices.

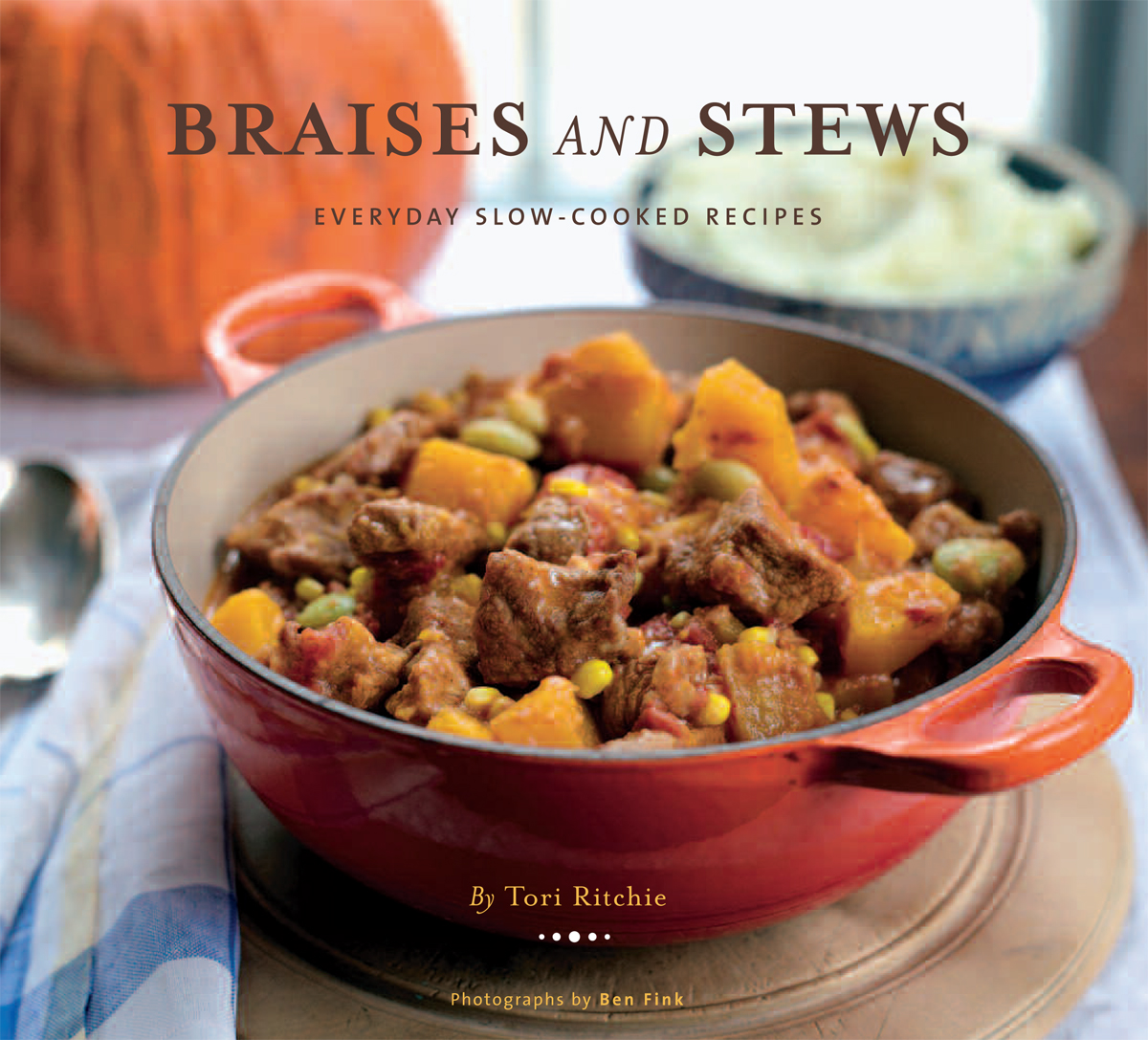

The best all-purpose pot for the recipes in this book is a Dutch ovena heavy, cast-iron pot with two loop handles and a matching lid. These pots heat up slowly, then retain and distribute heat exceedingly well. The best brands have bumps or spikes underneath the lid, collection points for steam which then drips back down into the food, reinforcing the cycle of flavors. Enameled-iron versions of Dutch ovens dont require seasoning and they come in peppy colors that you will be happy to see on your stove. They can be expensive, but theyll last forever.

Cladded stainless-steel, copper, or cast-aluminum versions of Dutch ovens may be labeled soup pot, stockpot, round oven, or, simply, braiser. Look for ones that are heavy and durable, with an aluminum or copper core to conduct heat, and a matching lid. I cannot stress enough how important it is that the pots lid fits snugly, but this varies from manufacturer to manufacturer. If the lid jiggles when you are braising, cover the top of the pot with foil, then place the lid over the foil, pressing down to secure the seal.

As a traditionalist, I think every home needs at least one 5- to 7-quart Dutch oven, and thats the most common pot called for in this book. The reason for the range is that different manufacturers use different sizing. My two favorite brands of enameled-iron pots Le Creuset and Staubare made in France and converted measurements can be awkward (like 7.25 quarts). Dont worry about that. A pot in this size range, that measures about 10 inches across, will cover almost every braising need. If you can afford it, a selection of different sizes and shapes, such as oval (perfect for chickens), will make braising even more fun.

A few other pans are useful, too. A wide (10- to 12- inch) saut pan is good for braising many things, such as vegetables and fish. I recommend anodized aluminum or cladded stainless steel that is heavy bottomed and has a tight-fitting lid. Another pan I use for some braises, like quick curries or shrimp, is a flat-bottomed wok (with a lid). Even though these are meant for stir-frying, the good-quality ones work well for the quick browning and stove-top simmering of a lighter braise. The tapered shape means the surface area is wide, which encourages evaporation and concentration of flavors. Nonstick ones are a snap to clean.

GOING DUTCH

The word Dutch in the term Dutch oven is said to have come from pots used by the Pennsylvania Dutch (who were actually Germans) in the 1700s. The oven part of the name came from placing the vessels, which originally had feet, in the embers of the hearth, then topping the lid with more coals (old-fashioned Dutch ovens have lipped lids) to create the all-around heat of an oven before ovens were commonplace in homes.

The other tools that you need to braise you probably already have in your kitchen: long tongs to turn meat while browning; wooden spoons to scrape the bottom of the pot; oven mitts to carry the pot safely; and a ladle to dish out hearty portions. Add in measuring cups and spoons and a sharp, heavy knife, and you are good to go.

STEPS TO BRAISING

Braising is as simple as cooking long, slow, and low so that each flavor in the pot gradually merges with the others, creating a savory whole far greater than its parts. The food may be browned first, then the pot deglazed, but the ingredients are always simmered, never rushed. Meat and poultry braises and stews have a few other steps, too, which are outlined here.