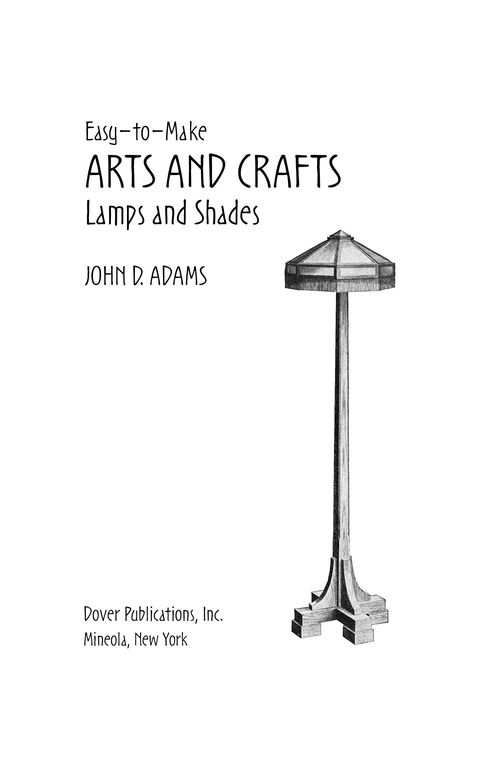

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2005, is an unabridged republication of Arts-Crafts Lamps, published by Popular Mechanics Co., Chicago, 1911.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Adams, John Duncan, 1879

[Arts-crafts lamps]

Easy-to-make arts and crafts lamps and shades / John D. Adams

p. cm.

Originally published Arts-crafts lamps. Chicago : Popular Mechanics, 1911 under the title: Arts-crafts lamps.

9780486174624

1. Electric light fixtures. 2. Lampshades. 3. Paper work. I. Title.

TH7960.A4 2005

749.63dc22

2005045466

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

T HIS book is one of the series of handbooks on industrial subjects being published by the Popular Mechanics Company. Like the Magazine, these books are written so you can understand it, and are intended to furnish information on mechanical subjects at a price within the reach of all.

The text and illustrations have been prepared expressly for this Handbook Series, by experts; are up-to-date, and have been revised by the editor of Popular Mechanics.

ARTS-CRAFTS LAMPS

INTRODUCTION

T HAT really artistic lampsportable ones for reading, pendant lamps for the porch, domes for the dining room, lanterns for the den, in fact, all manner of lamps that are usually made from expensive leaded glasscan be made from paper, cardboard and wood, may seem a trifle strange; but still stranger will it seem when it is stated that these results may be accomplished by almost anyone who has ever used a saw, plane and pocket knife, and is still in possession of a fair amount of patience. But, you will say, it is quite impossible that from cardboard and colored paper a shade can be produced that will be as beautiful as one of leaded art glass.

Of course, there is a difference, but it is very much less than would be imagined, and is hardly noticeable when the shade is illuminated. During the day time the colored paper is quite attractive, whereas the colored glass is very dull and often decidedly unattractive when not illuminated. But once more, you will object that the cardboard shade must be very frail. True enough, they will not stand as much crushing as a metal frame, but then shades usually break by falling, and falling can not harm our cardboard-paper shade, so that under ordinary conditions the latter is safer. However, be this as it may, cardboard formed into angles, properly braced and connected, becomes very rigid. Like a roof truss, its strength lies more in its shape than in the amount of material employed.

To restate our original proposition: Anyone with sufficient patience to avoid all hurry can, at home, at an almost negligible expenditure, produce a great variety of lamps, that will, nine times out of ten, be mistaken for the product of a professional rather than of an amateur. In this line of work, the results are invariably delightfully surprising.

Handicraft work is becoming more popular every day, and outfits for metal etching, perforated brass work, hammered copper and various other crafts, are now supplied by the large department stores. But none of these hobbies finds such a wide or important application in the home as the subject of lamps; and after the reader has become familiar with the general system of construction, and has gained the confidence that comes with some little actual experience, the work will be found intensely interesting. The effect on the eyes of a properly shaded lamp, the artistic effect in the combinations of various colors, the opportunities presented for individual ingenuity in adapting the color scheme to that of the room, will all be duly appreciated as the work proceeds. The largeness of the field will also prove attractive to the amateur craftsman. A hanging lantern for the porch, a chandelier for the living room, a dome for the dining room, a pair of bracket lamps for the den, a portable for the library table and shades for a drop light here and there about the house, will all be required.

Through all this work the general method is largely the same, so that after a few lamps have been made, the enterprising amateur will find ample opportunity to exercise his or her ingenuity in the way of adopting and combining such attractive features observed in other lamps that have struck the fancy, and finally will have the satisfaction of designing and constructing a lamp entirely from original ideas.

About all the tools necessary are those required for the little carpentry work in connection with the stands. A good sharp pocket knife with a large handle should be provided, and its point must always be kept particularly sharp, else the edges of the cardboard will be irregular and frayed. A roll of black passe-partout tape, some drop-black paint, a bottle of liquid glue, a box of brass paper fasteners, are all the necessary sup- , plies required besides the cardboard and colored papers.

CHAPTER I

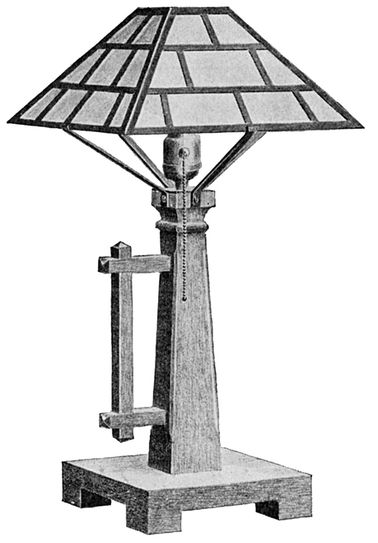

A ONE-LIGHT PORTABLE LAMP

L ET us first consider a one-light portable lampa lamp suitable for a desk or small table. The first thing to do is to lay out the pattern for one of the sides of the shade, which should be done on a flat and rather heavy sheet of paper, after which it should be carefully cut out with a sharp knife. A sheet of cardboard, 16 by 18 in., should now be procured. The reader should be cautioned against trying to work with too heavy a grade of cardboard. Select a moderate weight and test it by lightly scoring one side with a knife and bending it to a right angle, the knife mark always being on the outside of the bend. If the cardboard is cheap and short-fibered, the fact will be evident when so tested. Place the paper pattern on the cardboard and mark it off with a sharp pencil. Then move the pattern over one space, that is, move it until one edge exactly coincides with the outer pencil line of the first position, and mark off again, continuing the operation until the fourth and last side has been marked off. In this manner we obtain the complete pattern on our sheet of cardboard as shown. The dotted lines indicate those that are to be scored with the knife for bending, and the full lines those that are to be cut clear through. It is advisable that the cutting be done over a hardwood board, and in making the first pass with the knife do not press too hard, as the hand or straight edge is more apt to slip at this stage than when the cut has reached some depth. Any rough or torn edges should be smeared with glue and sandpapered when dry. When all the cutting has been done, place the line of bend directly over the sharp edge of a table or board and the straight edge over that portion remaining on the table, then bend gradually all the way along. The last edge of the fourth section has a connecting strip which should be covered with glue and then fastened to the first edge of the first section. The extra strips at the top and bottom should finally be bent inward to a horizontal position and fastened with a paper fastener at each corner. The corners of all bends should be reinforced with passe-partout tape. The entire framework is now to be painted a dull black, which, in anything but broad daylight, will be invariably mistaken for the usual iron work. Select some paper of the desired shade and color, and before attaching it, try the effect after dark by bending it around a light. Sometimes two or even more thicknesses may be necessary. Generally, in a tapering shade like this, the upper portion, which is nearer the light, appears brighter than the lower portion, in consequence of which a very pleasing and attractive blend from a lighter to a darker shade is obtained.