MATH BYTES

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire, OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chartier, Timothy P., 1969

Math bytes : Google bombs, chocolate-covered pi, and other cool bits in computing / Timothy P. Chartier.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16060-3 (acid-free paper) 1. MathematicsPopular works.

2. MathematicsData processingPopular works.

3. Computer sciencePopular works. I. Title.

QA93.C47 2014

510dc23

2013025378

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper

Typeset by S R Nova Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Noah and Mikayla,

snuggle up close,

I have math-nificent stories to share

before this day ends,

and then may your dreams lead you

to explore what you learn in new ways.

I await your stories.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

W HY STUDY MATH? can be a common question about mathematics. While a variety of answers are possible, seeing applications of math and how it relates to the world can be inspiring, motivating, and eye opening. This book discusses mathematical techniques that can recognize a disguised celebrity and rank web pages with the roll of a pair of dice. Math also helps us understand our world. How can poor reviews on Twitter impact a big budget films poor showing on opening weekend? How are fonts created by computers?

Mathematics has many applications, too many for any book. The purpose here is to cover and introduce mathematical ideas that use computing. Some of the ideas were developed by others, like Googles PageRank algorithm. Other ideas were developed specifically for this book, like how to create mazes from mathematical images created with TSP Art. The goal is to give the reader a good taste for computing and mathematics (thus a byte). Still, many ideas are not presented in their full depth with the mathematical theory or most complex (and robust) approach (thus a bit of math and computing).

This book is intended for broad audiences. It was developed in this way. For example, begins with math and doodling, which is adapted from content taught to non-majors at Davidson College. Later in the chapter, the content on the Traveling Salesman Problem and TSP Art was developed from lectures to math majors at Davidson College and the University of Washington. The chapter concludes with the creation of mazes, which is an application of these ideas developed specifically for this book. Other chapters have been adapted from ideas developed in my seminars with the Charlotte Teachers Institute. As such, teachers should find ideas that align with their curricular goals.

on the theory of PageRank, tend to appeal to mathematicians. This multileveled approach is intentional. Given the eclectic collection of ideas, I imagine a reader can delve into whats interesting and skim sections of less interest. Throughout the development of this book, readers have ranged from self-proclaimed math haters to professors of mathematics. Wherever you, as a reader, fall in this range, may you enjoy these applications of mathematics and computing.

Throughout the book, youll find hands-on activities from using chocolate to estimating to computing a trajectory of flight in Angry Birds. I expect such explorations to be a tasty byte of math and computing for many readers. If you enjoy these investigations, I encourage you to view the supplemental resources for this book at the Princeton University Press website; youll find such materials at http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10198.html.

My hope is that this book will broaden a readers perspective of how math can be used. So, when someone turns to you and asks for a reason to study math, youll at least have one, if not several, reasons. Math is used every day. Such applications can be enjoyed and appreciated even if you simply consider a bit and a byte of it.

Acknowledgments. First and foremost, I thank Tanya Chartier who walks this journey with me and affirms choices that lead to roads less travelled and sometimes possibly even untrodden. Tanya encouraged me to write the first draft of this book when it was clearest in my mind during my sabbatical at the University of Washington in Seattle. Thank you, Tanya, for such wise counsel. Im grateful to Melody Chartier for being my first reader as her input supplied great momentum and the ever-present goal of reaching a broad audience. I also thank Ron Taylor, Brian McGue, and Daniel Orr for their readings of the book. I enjoyed developing the Jay Limo story and chocolate Calculus with Austin Totty. Im grateful for the various lunch conversations with Anne Greenbaum that largely led to our coauthored text [18] but also inspired a variety of ideas for this book. I appreciate Davidson Colleges Alan Michael Parker for encouraging me, when I thought I was done with an earlier draft, to write my book with my voice. Having studied mime with Marcel Marceau while I pursued my doctorate in Applied Mathematics, it seems almost natural to have written a book that computes with chocolate, finds math in a popular video game, and explores math in sports. As such, I believe this book reflects my journey as a mathematician and artist. I thank my parents who taught me to apply my learning beyond preset boundaries and to look for connections in unexpected areas. Finally, I appreciate the many ways Vickie Kearn has supported me in this writing process and her guidance, friendship, and encouragement. It is difficult, if not impossible, to thank everyone who played a part in this book. To colleagues, students, and friends, may you see your encouragement and the results of conversations in these pages.

MATH BYTES

Your First Byte

M ATHEMATICS HELPS CREATE THE LANDSCAPES on distant planets in the movies. The web pages listed by a search engine are possible through mathematical computation. The fonts we use in word processors result from graphs of functions. These applications use a computer although each is possible to perform by hand, at least theoretically. Modern computers have allowed applications of math to become a seamless part of everyday life.

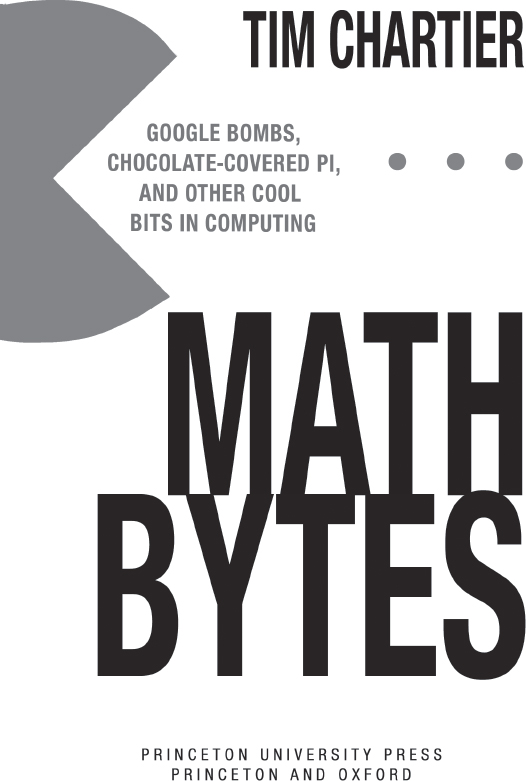

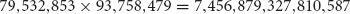

Before the advent of the digital computer, the only computer we had to rely on was a persons mind. Few people possessed the skill to perform complex computations quickly. Johan Zacharias Dase (18241861) was noted for such skill and could mentally multiply

in 54 seconds, two 20-digit numbers in six minutes, two 40-digit numbers in 40 minutes, and two 100-digit numbers in 8 hours and 45 minutes. As another example, Leonhard Euler, the most prolific mathematical writer of all time with over 800 published papers, was renowned for his phenomenal memory. Such ability became important during the productive last two decades of his life, when he was totally blind. He once performed a calculation in his head to settle an argument between students whose computations differed in the fiftieth decimal place.

Next page