CHILD MIGRATION AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN A GLOBAL AGE

|

Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity |

Eric D. Weitz, Series Editor |

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book. |

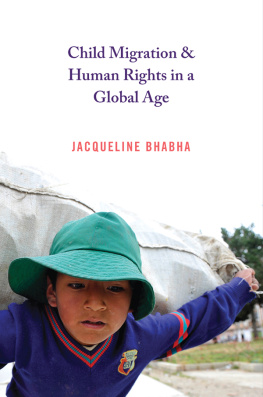

Child Migration & Human Rights in a Global Age

Jacqueline Bhabha

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-14360-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013954741

Credits for the chapter opening photographs are as follows:

Chapter one, copyright BID; chapter two, courtesy of KPBS; chapter three, UNICEF/NYHQ2012-1924/Dormino; chapters three, four and seven, International Labour Organization/Crozet M.; chapter six, Heba Aly/IRIN.

Jacket Photo: Young Boy Carrying Plastic Bottles, La Paz (Alto), Colombia. International Labour Organization/Marcel Crozet. Courtesy of the Photo Library of the International Labour Organization.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my Homi, Ishan, Maria Elisa, Satya, and Leah

Contents

Acknowledgments

Any book that spans a large part of ones working life reflects the impact of relationships extending far beyond work. This book is no exception. The concerns it describes have been with me since I was a graduate student at Oxford. They developed during my years as a practicing lawyer and activist in London. They still preoccupy me decades later at Harvard. Deciding whom to thank is thus a daunting task. Stray conversations, engaging arguments, nurturing distractions, generous collaborations, insightful suggestions, probing questions, frank testimonies, rigorous critiques, and loving relationships have all played a crucial role. To avoid an endless list, I only mention a few among the very many people I am grateful to.

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to colleagues I have worked with closely on immigration-related issues over the yearsSylvia Whitfield in Birmingham; Nony Ardill, Don Flynn, Elspeth Guild, Francesca Klug, Sue Rowlands, Sue Shutter, and Nira Yuval-Davis in London; Arjun Appadurai, Bernardine Dohrn, Susan Gzesh, Rashid Khalidi, Mary-Meg McCarthy, Mae Ngai, and Maria Woltjen in Chicago; Susan Akram, Deborah Anker, Elizabeth Bartholet, Dan Kanstroom, Nancy Kelly, Gerald Neuman, Susannah Sirkin, and John Wiltshire-Carrera in Boston; Mary Crock, Nadine Finch, and Susan Schmidt on the three-country Seeking Asylum Alone project; Kate Halvorsen, Judith Kumin, Michle Levoy, Nevena Milutinovic, Siobhan Mullaly, Elena Rozzi, Daniel Senovilla Hernandez in Europe; and, across North America, Alex Aleinikoff, Susan Bissell, Patty Blum, Linda Bosniak, Michle Branl, Catherine DAuvergne, Barb Frey, Lisa Frydman, the late Arthur Helton, Kay Johnson, Linda Kerber, Stephen Legomsky, Yali Lincroft, Audrey Macklin, Susan Martin, Chris Nugent, Geraldine Sadoway, Andrew Schoenholtz, Debora Spar, Peter Spiro, David Thronson, Steve Yale Loehr, Wendy Young.

Many others have been sources of enrichmentintellectual, political, institutional, personalover my years at both the University of Chicago and Harvard. I am most grateful to James Chandler, John and Jean Comaroff, Norma Field, Michael Geyer, Mona Khalidi, Elizabeth OConnor Chandler, Geof Stone at Chicago; and, at Harvard, Michael Blake, Charlie Clements, Liz Cohen, Stanley Hoffmann, Steven Hyman, Michael Ignatieff, Doreen Koretz, Michle Lamont, Margaret McKenna, Martha Minow, Gerald Newman, John Ruggie, Beth Simmons, Henry Steiner, Lucie White. Sincere thanks are owed to Gus and Rita Hauser and to the Hauser Foundation for most generous support of my work over several years at Harvard. I am also greatly indebted to many librarians, research assistants, students, and administrative colleagues for superb help on a huge range of matters, from fact checking and legal research to technical assistance and editorial work. I am particularly grateful to Trevor Bakke, Ivelina Borisova, Molly Curren, Sarah Dougherty, Susan Frick, Lyonette Louis Jacques, Adam Kern, Ita Kettleborough, Yoojin Kim, Angela Murray, Bonnie Shnayerson. My colleagues at the Franois-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard UniversityHeather Adams, Theresa Betancourt, Arlan Fuller, Liz Gibbons, Orla Kelly, Magda Matache, Anne Stetson, Aly Yaminare much more than fellow workers; they are friends and co-conspirators in much of what I do. I would not have managed to finish this book without their generous comradeship.

I am fortunate to have had editorsBrigitta van Rheinberg and Eric Weitz at Princeton University Presswho were always there when I needed them but left me to my own devices otherwise. I am also grateful to a terrific copy editor, Marsha Kunin, and to two anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable feedback, without which this book would have been much less accurate and coherent.

As an itinerant jack of several trades and mistress of none, I have again and again depended on several close friendships for encouragement, support, and the sense of belonging that nurtures the confidence to write. I am immensely grateful to Riccardo Bottelli, Martha Chen, Ana Colbert, Nancy Cott, Caroline Elkins, Diane Fernyhough, Stephen Greenblatt, Julian Henriques, Anish Kapoor, Susanne Kapoor, Joseph Koerner, Meg Koster, Jennifer Leaning, Bikhaji Maneckji, Zareer Masani, Luigina Palmiero, Diana Sorensen, and Ramie Targoff.

Finally, my beloved family are the bedrock on which all else depends: Naju Bhabha, Oliver and Harriet Strimpel, Michal and Moshe Safdie, Shanta, and then of course, Homi, Ishan and Maria Elisa, Satya and Leah. A child and adult migrant survives and thrives because of the relationships she is fortunate to enjoy. I hope this book contributes to this same anchoring for others.

CHILD MIGRATION AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN A GLOBAL AGE

Introduction

Every year, tens of thousands of children cross borders alone. Some travel to join families that have already migrated. Others leave home to flee war, civil unrest, natural disaster, or persecution. Some migrate in search of work, education, opportunity, adventure. Others travel separated from their families but not actually alone, in the company of traffickers or smugglers, risking exploitation and abuse. The majority, perhaps, travel for a combination of reasons, part of the growing trend toward mixed migration. And yet, the complexity of child migration is a largely untold and unanalyzed story. This book is an effort to correct that omission.

Child migration is part of a contemporary phenomenon that changes and shapes the world we live in. Migration affects not just the 3 percentclaim to protective intervention or fiscally backed social engagement is ever-diminishing now that concerns about the Holocaust and the brutalities of the Cold War have given way to apprehensions about terrorists and welfare scroungers. Children do not feature in this large-scale picture, except as occasional appendages to adults. But they should. The failure to attend to child migration coincides with the diffusion of confused, unsatisfactory, and frequently oppressive policies that should not stand up to careful public scrutiny.

Next page