CONTENTS

List of Recipes

About the Book

The Ethicurean philosophy is simple: eat local, celebrate native foods, live well.

The Ethicurean is quietly changing the face of modern British cooking all from a walled garden in the heart of the Mendip Hills. The Ethicurean Cookbook follows a year in their magnificent kitchen and garden and celebrates the greatest food, drink and traditions of this fair land.

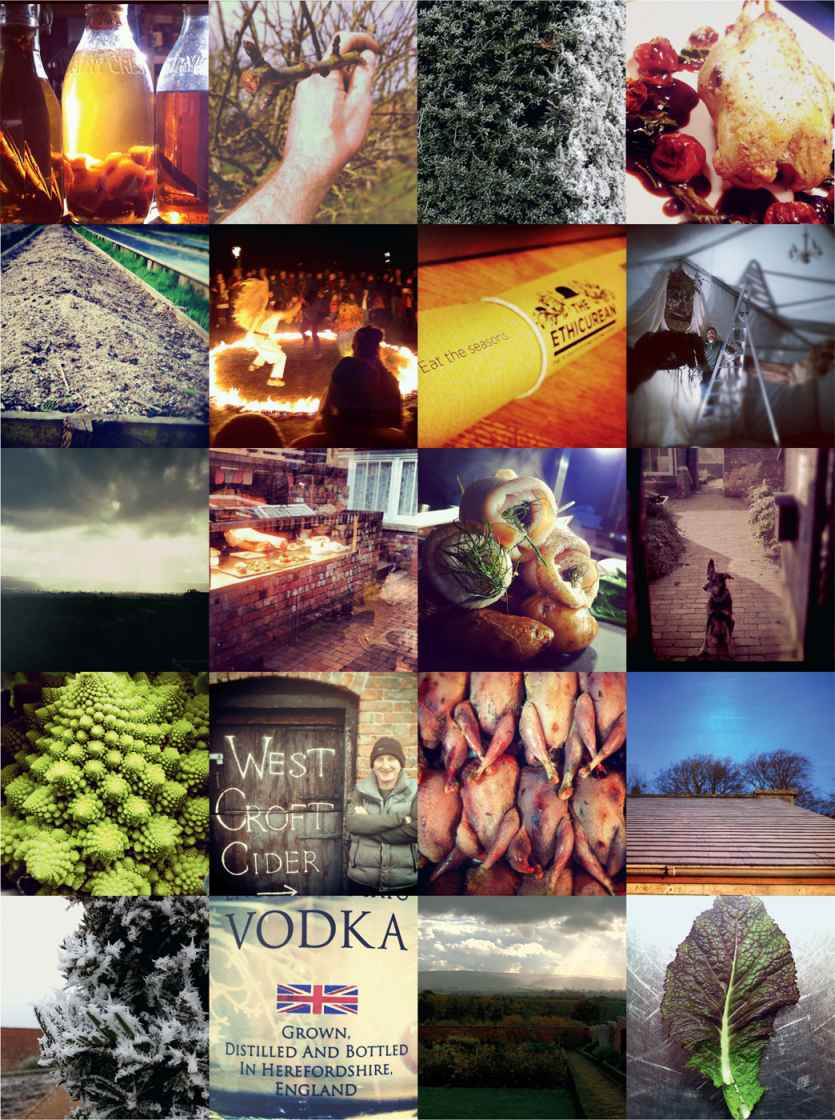

The combinations are electric: cured roe deer flirts with wood sorrel, and foraged nettle soup is fortified by a young Caerphilly. Honeyed walnuts nestle amongst beetroot carpaccio, rich curd cheese is balanced by delicate cucumber. And the comfort of pies and pud pork and juniper pie, Eccles cakes with Dorset Blue Vinny is enhanced by the apple juice, cider and beer poured in equal measure.

With 120 recipes and a year of seasonal inspiration in photographs and words, Ethicureanism is a new British cooking manifesto.

The Ethicureans are Jack Adair-Bevan, Pala Zarate, Matthew Pennington and Iain Pennington.

Above, left to right: Jack, Matthew, Ocho, Pala and Iain

Cooks Notes

All vegetables are peeled unless otherwise specified.

All eggs are medium, free-range.

Butter is unsalted, unless otherwise specified.

ethicurean adj. the pursuit of fine-tasting food while being mindful of the effect of ones food production and consumption on the environment

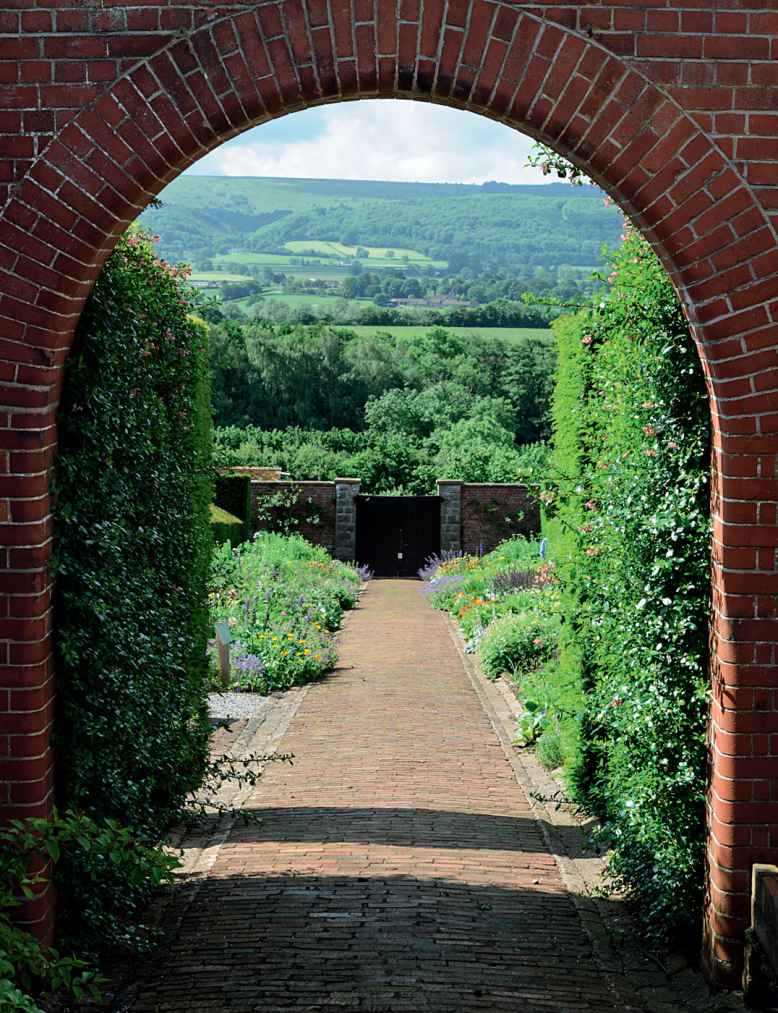

The Ethicurean sits below an overgrown Georgian estate, sometime haunt of Wordsworth and Coleridge. Its gardens are a labyrinth of roses, pergolas and chipped statues. The restaurant and kitchen are housed in two of the original glasshouses within Barley Wood Walled Garden, built for Henry Herbert Wills of the Imperial Tobacco Company in 1901. This was the year in which Queen Victoria took her final breath. Our Walled Garden is filled with neat rows of cabbages and espaliers of greengages and apricots. Hundred-year-old vines have bullied their way through a small brick hole in one of the glasshouses. Cambered red-brick paths frame a patchwork garden of cannellini beans, marching Tom Thumb and a quilted statis. The garden is cut in half by a yew-lined corridor; in spring lavender grows at just the right height to tear off small handfuls as we walk up from the lower orchard. In summer the purple mass gives way to campanula, day lilies and hundreds of aster. Mark, the gardener, brings us trugs of vegetables each morning and the starched white flash of a chefs tunic can be seen around the herb borders just before lunch.

British seasonality, ethical sourcing of ingredients and attention to the local environment are the foundations of our business. We are four friends: Jack Adair-Bevan, Pala Zarate and Matthew and Iain Pennington. Between us we have overlapping areas of expertise that range from the practical and organisational knowledge needed to run a business, to the science of cooking and the wild food that grows outside the walls of our restaurant. We are self-taught and want to offer an approach to British food that is neither exclusive nor isolating; and one that is fundamentally about sharing knowledge and passion.

Sustainability has become a buzz word in recent years, and all anybody can ever do is work towards a more sustainable way of life we Ethicureans are doing our best. We took over the restaurant in 2010: over five days we completed a refit with the help of our family and friends, knocking down walls, redecorating, and pausing only to take a decent lunch and supper on the long tables overlooking the Wrington Vale. On the sixth day we opened for business and began a full apple season, picking, pulping and juicing. We started researching the seventy varieties of apple that we now had to look after in our two orchards.

Food and the narrative surrounding it is in a constant state of evolution: it is political, artistic and completely delicious. The Mendips in Somerset, the home of The Ethicurean, is a place on the verge of something incredible. Artisans from across the country are moving their production here. Community farms, orchards and collaborations are popping up across the county. We are watching day by day as our friends, customers and suppliers are re-establishing and strengthening their rural communities and taking control of their food production. We are seeing and enjoying the rediscovery of old techniques and adaptations for the future.

From our opening day, we changed our menu on a daily basis according to what was available; we continue to celebrate every single day of the British season. In this book we have recorded not only recipes, but our relationships with our producers, our land, our lives and our history all of which are intricately connected with the food we eat.

We rarely leave this beautiful walled garden; it is an absolute paradise.

Recipe List

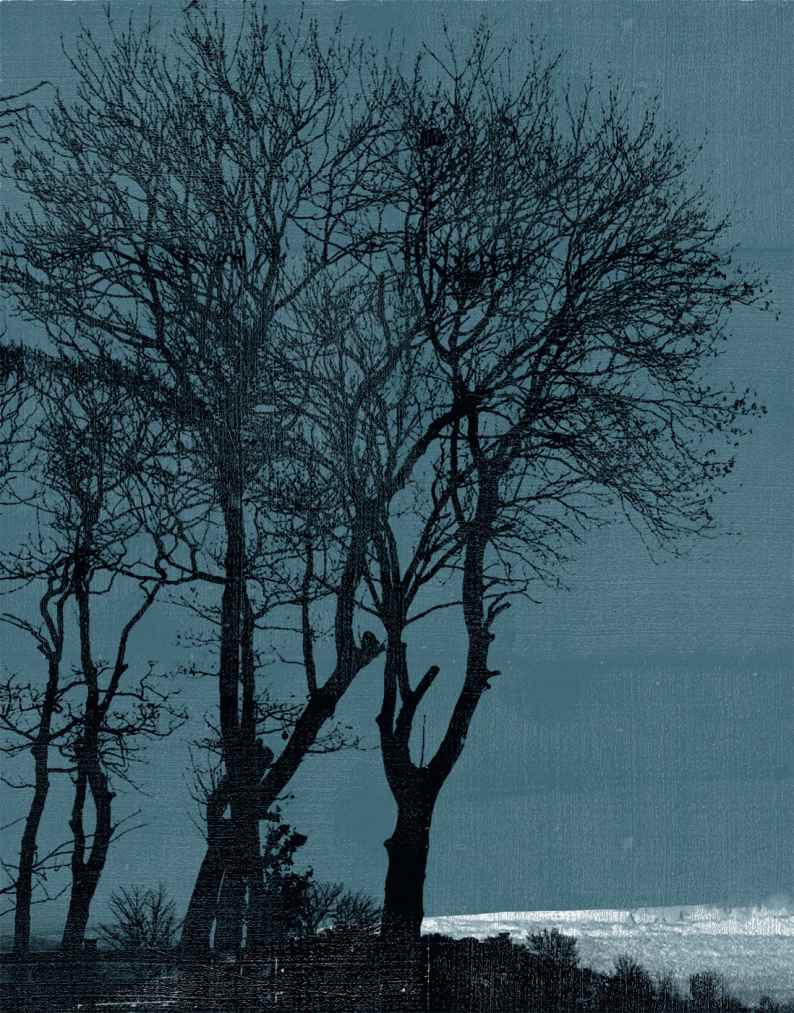

THERE ARE A COUPLE of special requirements for the Walled Garden in winter first, a lighter to defrost the padlocks and secondly a good torch for evening trips around the garden, unless there is a full moon. Frosts in the Wrington Vale are spectacular. The air hoar that decorates the trees creates a landscape that is more akin to Siberia than Somerset. In an early-morning drifting fog, the view from the glasshouse is divine. During our first year at Barley Wood, we had heavy snow and several hoar frosts, and the pathway through the centre of the garden lay under a good three inches of snow. Jack clipped on his skis and, armed with two bamboo canes pinched from Marks beans, managed to ski right through it. Morning trips to the compost heap at the bottom orchard, the reserve of the luckiest in summer, become a task to be avoided by all of us.

By early December we try to finish pressing the last of the seasons apples, as working in the icy cider barn is harsh. Elena, Palas mum, and Phil, Jacks dad, run the apple business. Both are used to warmer climates Mexico and the Gulf respectively. Youll find them in the barn, clothed in multiple layers, debating which varieties of apples to blend. Their fridges at home are bursting with labelled specimens: Tydemans Late Orange sits next to Reverend James. The seasons last pressings require juggling the final few trugs of sweet varieties with the later cookers, such as the infamous Bramley and the cloud-textured Blenheim Orange.