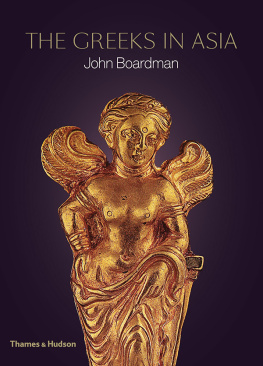

Indian gold finial inscribed OEA or 'goddess'. See .

For JULIA

About the Author

John Boardman is Professor Emeritus of Classical Archaeology and Art at Lincoln College, Oxford. His previous books for Thames & Hudson, published over a period of fifty years, include: The Greeks Overseas; The World of Ancient Art; The Archaeology of Nostalgia; and multiple volumes in the World of Art series: Greek Sculpture; Athenian Red Figure Vases (volumes on the Archaic Period and the Classical Period); Athenian Black Figure Vases; Early Greek Vase Painting; Greek Art; and Greek Sculpture (with volumes on the Archaic and Classical periods). He is also a joint author of The Oxford History of the Classical World, The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World, and The Oxford History of the Roman World.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Greeks Overseas

Their Early Colonies and Trade

Persia and the West

An Archaeological Investigation of the Genesis of Achaemenid Art

The Making of the Middle Sea

A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginningto the Emergence of the Classical World

The Great Empires of the Ancient World

Art & Archaeology of the Greek World

A New History, c. 2500 c. 150 BCE

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

Preface

In 1948 I met an elderly Greek man on the island of Naxos who said he had been with General Kitchener at Khartoum. As a boy he was helping his father sell lemonade to the British troops, undercutting the prices of the local Arab shopkeepers. The episode seemed typical of that Greek private enterprise and success far from home which was as apparent in antiquity as it is today, commercial rather than militant or imperial consider Greek millionaire shipowners. It may be that this quality was one imposed by the relative poverty of the homeland. When the first Greek-speakers approached the Mediterranean from the north they found themselves ushered into a peninsula whose southern extremity was far less well provided with arable or pastoral plains than most of the other countries bordering the Mediterranean; not at all like Italy or Spain. It inevitably led to a complex of independent and often competitive states rather than a united country, and this was apparent already under the Mycenaean Greeks in the Bronze Age, with their separate kingdoms and fortress capitals. Many Greeks took to the seas and looked to improve their fortunes elsewhere. The ancient world was a relatively small place: Indian cinnamon could be found in the Heraion of Samos in the 7th century BC, but had travelled hand-to-hand; amber arrived from the Baltic. But the Greeks would soon learn the merits of distant travel for themselves.

They had come from the north and east originally. Their presence in Greece, as what we call Mycenaeans, already provided opportunities to demonstrate their readiness to look both east and west, to Anatolia, to Cyprus, to Italy. Barely three centuries after the fall of the Mycenaean world in around 1200 BC their attention again inexorably turned away from the homeland. To the west they were partly looking for new homes, but were mainly acquisitive of the products and wealth of peoples of, by comparison, relatively modest cultural accomplishment and no threat.

The results were to mutual benefit: the Greeks grew richer and found some new homes; the westerners were introduced to a wider world for their produce, to a monetary economy, to literacy, and to an art that could express narrative explicitly, after some centuries of relative stagnation. They were not physically threatened. This is not quite colonization in the modern sense of the word, but there are points of comparison and any sensible scholar or student is not misled by use of the word.

In the eastern Mediterranean the Greeks reintroduced themselves to the heirs of the great civilizations and empires of the Near East, and submitted to an orientalizing revolution in their arts, which was to lead inexorably to the classical revolution of the 5th century BC and the genesis of a mode of classical civilization to which the whole Western world remains heir.

This book is about what happened when Greeks met easterners Anatolians, Levantines, Persians, Asiatics, Indians; how they interacted and what effects there were on the arts and societies of distant lands being visited and even settled by these folk, whose own traditions had evolved through various forms of kingship, tyranny and empire, and whose arts had passed from the formal and abstract to a degree of observation of life and nature not attempted elsewhere in the then civilized world. And they were visiting settled civilizations far older than theirs, with their own strong traditions in life, government and the arts, of a yet more decisive and individual cultural stamp than the Greek. As elsewhere in the world, these interfaces between cultures present a fascinating study of how human societies evolve, and how progress is as at least as often the product of interaction as it is locally generated.) in the attempt to keep like with like. The Roman is also a problem since the Roman Empire spread east to as far as Mesopotamia and (much) later dealt directly with southern India. I have therefore to address the problem of Greek or Roman arts and, without, I hope, demoting the Roman, stress the Greek character of so much in Roman Asia and especially at Alexandria in Egypt, which were the main sources of the classicism that passed east.

My treatment of the subject is not exhaustive, since there are several histories of the period and subject available, as well as thorough bibliographies and lists of sources. It tends to favour the primary evidence physical, archaeological, artistic and literary, too often scorned by latter-day scholars since this is often less easily found by the reader and has long been my main interest. Here too I am much dependent on the resources of a good library and the information supplied by colleagues.

The Greeks were not empire-builders, and for the most part the Asian cultures they met were far better organized to control great tracts of land, to aspire to ambitious conquest and to influence and eventually absorb other peoples. The Greeks had no such vision, and spent much of their time trying to foil each other. But they had other qualities which could be valued anywhere, as they had been in the west: they were adept at trade, they could be good accountants and organizers for others, they were highly literate, they spread a monetary economy for Eurasia, their religion was not too demanding and easily adapted to that of others, and their art developed a form of narrative that was to be dominant for centuries to come. Their poets and philosophers were widely respected outside their homeland. They are an odd phenomenon in world history, and through their travels they came to leave a very distinctive imprint on the lives and arts of many distant peoples, and over centuries, some to the present day.

My interest in the subject was generated at an early date by preoccupation with evidence for Greeks visiting the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, in Syria, as pirate-traders, in the 9th/8th century BC, as demonstrated by the type of Greek pottery they carried and which was locally copied. This revealed them to be from the island of Euboea, which was, we know, also the source of those Greeks who were starting to explore the western Mediterranean coasts, North Africa, Italy and Sicily. Their closest rivals were the Phoenicians, who were more ambitious, less versatile. All this led me to a more general study of Greeks overseas (the title for a book in 1964, much revised since, to 1999) in the earlier period. My enthusiasm was expanded as a result of travel, to Persia, Afghanistan, India and East Asia, of involvement in the

![Michael Lovano - The World of Ancient Greece: A Daily Life Encyclopedia [2 Volumes]](/uploads/posts/book/268736/thumbs/michael-lovano-the-world-of-ancient-greece-a.jpg)