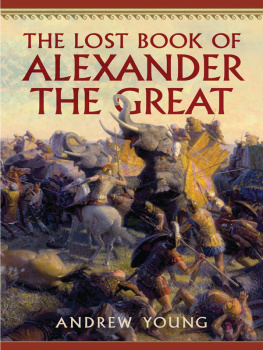

Alexander

the Great

From His Death to the Present Day

JOHN BOARDMAN

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018935462

ISBN 978-0-691-18175-2

eISBN 978-0-691-18404-3 (ebook)

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Ben Tate and Hannah Paul

Production Editorial: Sara Lerner

Text and Jacket Design: Carmina Alvarez

Jacket Credit: From Charles le Brun (161990), The History of Alexander, woven silk and wool tapestry (297.0 229.0 cm) showing Alexander the Great entering Babylon. Blenheim Palace, Woodstock. Photo by Julia Boardman.

Contents

vii

ix

Preface

Some talk of Alexander

And some of Hercules

Of Hector and Lysander

And such great names as these.

T he British Grenadiers marching song places Alexander the Great at the head of famous military commanders of both myth and history. The British Army has also always found a place in its heart for the Spartan Ly-sander, who defeated the Atheniansbut perhaps he was included in the song because he rhymed with Alexander. Hercules, a demigod rather than a soldier, and Hector, an epic Trojan prince, but killed by Achilles, were powerful figures of Greek myth/history, although not as successful as the mortal Alexander in terms of world conquest. The nearest divine match for such a hero was the Greek god Dionysos (Roman Bacchus), who earlier had been said to have travelled much the same path to the east, even to India, in his role of persuading the world of the importance of wine, and wielding the cup rather than the sword.

The early eighteenth-century soldiers song goes on:

Those heroes of antiquity

Neer saw a cannonball

Or knew the force of powder

To slay their foes withal.

Alexander means protector of men rather than destroyer, and this, together with our heros reputation, made it popular not only in antiquity, but more recently as a name for Russian and German emperors, even popes, for rulers rather than generals (other than General Alexander in North Africa, facing Rommel). In Britain we have recently celebrated the royal christening of Prince George Alexander Louis of Cambridge, while our recurrently popular politician Boris Johnsons first name is Alexander. But today Soviet Russian ballistic missiles are called by Alexanders eastern nameIskander.

He told me that he attended my Greek Sculpture lectures in Oxford, my only Alexander connection, other than my good friend, Professor Alexander Cambitoglou, in Sydney but first met in Athens.

Abbreviations

AWE: Ancient West and East (Leiden: Peeters)

Boardman, Diffusion: J. Boardman, The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994)

Bosworth/Baynham: A. B. Bosworth and E. J. Baynham, Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000)

Chugg, Lovers: A. Chugg, Alexanders Lovers (Bristol, 2006)

Chugg, Quest: A. Chugg, The Quest for the Tomb of Alexander the Great (Austin, Texas: AMC, 2007)

Fraser, Alexandria: P. M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972)

JHS: Journal of Hellenic Studies (London)

Lane Fox, Alexander: Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Great (Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Books, 1973)

Lane Fox, Search: Robin Lane Fox, The Search for Alexander (Boston: Little, Brown, 1980)

Nigg, Beasts: Joseph Nigg, The Book of Fabulous Beasts (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

Ogden, Alexander: Daniel Ogden, Alexander the Great, Myth, Genesis and Sexuality (Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 2011)

Prabha Ray/Potts, Memory: H. Prabha Ray and Daniel Potts, eds., Memory as History: The Legacy of Alexander in Asia (New Delhi: Aryan Books Int., 2007)

Rapelli, Symbols: P. Rapelli, Symbols of Power in Art (Los Angeles: Getty, 2011)

Ross, Studies: D.J.A. Ross, Studies in the Alexander Romance (London: Pindar Press, 1985)

Saunders, Tomb: N. J. Saunders, Alexanders Tomb (New York: Basic Books, 2006)

Search: The Search for Alexander, an Exhibition (Washington, DC: National Gallery, 1981)

Stewart, Faces: A. Stewart, Faces of Power. Hellenistic Culture and Society, 11 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993)

Stoneman, Greek: R. Stoneman, The Greek Alexander Romance (London: Penguin, 1991)

Stoneman, Legends: R. Stoneman, Legends of Alexander the Great (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994, repr. 2012)

Stoneman, Life: R. Stoneman, Alexander the Great: A Life in Legend (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008)

Stoneman et al. 2012: The Alexander Romance in Persia and the East, ed. R. Stoneman, K. Erickson, and I. Netton (Groningen: Backhuis, 2012)

Veloudis, Alexander: D. Veloudis, Alexander der Grosse. Ein alter Neugrieche. Tusculum Schriften (Munich: Heimaran, 1969)

Yalouris: N. Yalouris, Alexander and His Heritage, in The Search for Alexander, an Exhibition (Washington, DC: National Gallery, 1981)

Zuwiyya, Companion: Z. D. Zuwiyya, A Companion to Alexander Literature in the Middle Ages (Leiden: Brill, 2011)

Alexander

the Great

Introduction

T he reader should be warned that my story (rather than study) is only very marginally devoted to the real Alexander, but is almost wholly concerned with stories told about him after his death, both about historical events and, especially, the fantasy that scholars and poets have woven around him from antiquity down to the present day, from ancient and mediaeval Romances to modern film. His name and career have been used by authors, historians, and artists, relentlessly. They take us over a very full range of European and eastern literature and art, from Scotland to China, as well as of geography, since the whole of the Old World was deemed to have been the setting for his adventures, especially Asia. In the latter case, what I write depends rather little on personal experience of the eastern areas described (certainly not the imaginary ones, as yet) although I have tourist-travelled Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, north India, Ceylon, and China. My principal written sources are those I have abbreviated, and the many cited in footnotes, and which I have found in the Sackler Library in Oxford or via Abebooks. I should note especially my debt to Richard Stoneman for his many books published on the Romance aspects of the subject over the last twenty-odd years and his comments on what I have written. George Huxley and Paul Cartledge also kindly read a late draft of my text and offered many useful corrections and additions, as have others, notably Olga Palagia. Claudia Wagner has been exceptionally helpful in the preparation of the text and references to academic sources. But the reader will also surely be aware of my plundering of the Internet, verified where I could. So I would not claim this as a work of original scholarship, except in its assembly, but I hope it will appeal to some scholars unfamiliar with this area, somewhat removed from real history yet reliant upon it as well as upon the imagination of numerous writers and artists, east and west. It also has, I believe, a certain entertainment value. It is the product of a desultory but fairly thorough skimming of many different sources, an activity that has given me much pleasure, which may be, I hope, in part shared by the reader, if for no other reason than that the possibilities of expanding it seem endless. The evidence and sources are confusing, like the stories themselves, and I cannot deny having added somewhat to the confusion. Nor would I claim for this any degree of completeness. I find new references daily, but there had to be an end.