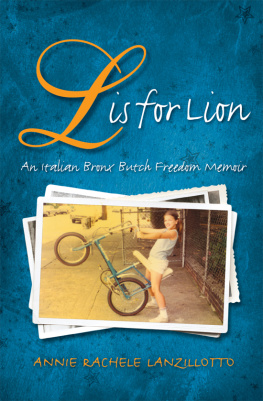

PRAISE FOR L IS FOR LION

Annie Lanzillotto, the bard of Bronx Italian butch, is an American original, a performance artist and cultural anthropologist whose work is unique in theme, sound, affect, and effect. This memoir reveals her to be something more: an astonishing writer possessed of an utterly inimitable voice, a voice at once as richly soulful as her mother's lasagna and as bracingly unsentimental as her father's Marine masculinity. Lanzillotto's stories bounce and stretch with the elasticity of her trusted Spaldeen, keeping us just a step ahead of the flying emotional shrapnel of an intensely lived life as we move from the mean streets of 1970s Bronx to the Ivy League, the Memorial Sloan-Kettering cancer ward, the banks of the Nile, and the Italian mezzogiorno. A landmark of ethnic expressivity, L Is for Lion indelibly portrays the iconic Italian American spaces of kitchen, stoop, sidewalk, and street; the body as a site of humor and tragedy; and, above all, the family war zone as an uncanny intermingle of poignancy and brutality.

John Gennari, author of Blowin' Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics

L Is for Lion is a book about a girl named Daddy who goes to Brown but never leaves the Bronx. This long-awaited memoir by lesbian storyteller and performance artist Annie Lanzillotto traverses the distance from Arthur Avenue to Cairo to Sloan-Kettering and back again in an ethnography of the self and of an era. It's a book made of dismantled padlocks, and of doors, opened and closed; of spoons clanking against radiators in an attempt to speak or scream; of Ivy League classism and World War II racism; of language spoken and broken. Equal parts humor, guts, and grief, it's a disarming story of all that a personbody, mind, and soulcan undergo without going under, in which Bronxite is a new kind of rock.

Mary Cappello, author of Awkward: A Detour and Called Back

SUNY SERIES IN ITALIAN/AMERICAN CULTURE

FRED L. GARDAPHE, EDITOR

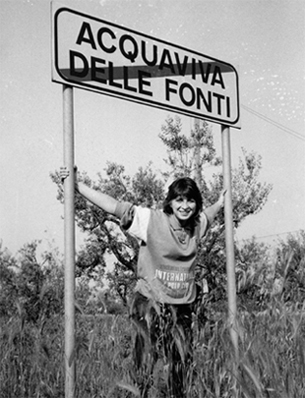

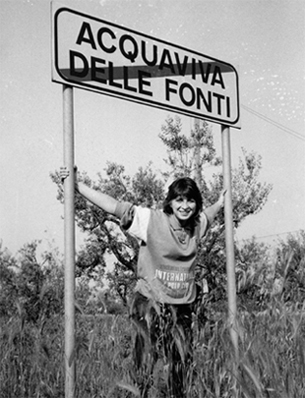

Me at the town limits of Acquaviva delle Fonti, Bari, Italia. I was jogging with my cousin Tonino out into the fields.

Photo: Antonio Lepenne, 1986.

Illustrations by Rose Imperato

Published by

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS, ALBANY

2013 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production and book design, Laurie Searl

Marketing, Fran Keneston

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Lanzillotto, Annie Rachele.

L is for lion : an Italian Bronx butch freedom memoir / Annie Rachele Lanzillotto.

p. cm. (SUNY series in Italian/American culture)

Excelsior Editions.

ISBN 978-1-4384-4525-0 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Lanzillotto, Annie Rachele. 2. Italian American lesbiansNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 3. Italian AmericansNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 4. Bronx (New York, N.Y.)Biography. I. Title.

HQ75.4.L36A3 2013

306.76'63092dc23

[B]

2012009553

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for my Mother, my best friend

No matter where you go,

you have to suffer aggravation,

and you have to suffer joy.

Granma Rosa Marsico Petruzzelli

You are a little soul carrying around a corpse.

Epictetus

All things fade into the storied past.

Marcus Aurelius

prologue

The Blue Suitcase

S eptember 16, 1962, domestic violence cases in New York State were transferred from Criminal Court to the newly established New York State Family Court. Assault of a stranger outside your front door was punishable to the full extent of criminal law, while assault of a family member inside the front door was not. Marriage became a license for abuse. Two weeks later, I was conceived. I said, I better go down and protect that woman, the courts ain't gonna do shit.

What better way to heal this family than a beautiful baby girl?

Family Court had no muscle. Victims were referred to civilian agencies for help. My mother's case was referred to the Salvation Army and then switched to Catholic Charities. Family Court did not have the power of the State of New York behind the plaintiff. This is the stage on which I was born, on Saint Raymonds Avenue in the Bronx.

Our street was named after Saint Raymond Nonnatus, or, the not-born; Raymond was taken from his mother's uterus postmortem. As an adult, he bartered for the freedom of slaves by trading himself into captivity, where he exuberantly preached. To stop his inspirational speaking, his lips were pierced and locked with a padlock. As an offering for Saint Raymond's intercession, supplicants leave padlocks on altars. My father, perhaps knowingly, did one better. The last decade of his life, while in a residential mental home, he dismantled padlocks that he found when he scavenged the neighborhood trash. It's not an easy task. Padlocks are built of two dozen intricately cut steel plates fashioned together by pins and a yoke. After my father was done with them, the last thing these wildly cut steel plates and pins resembled was a padlock.

My parents were married in 1947, after my father returned home from World War II. Anticipating the trips they would take, my mother bought a royal blue leather suitcase at Gimbels. It had hard walls and thick brass hinges that popped open with a catch. The blue suitcase stayed under her bed for fifty years, twenty-five with my father, and twenty-five after she escaped the brutal reality that had become la vita quotidiana, their daily life. With the blue suitcase, she ran for her life. She slid it under her bed, full of her keepsakes; my name bracelet from birth, all her children's oversize kindergarten diplomas, newspapers from the first lunar landing and of Joe DiMaggio's career milestones, old coins. Every few years she would open the suitcase to find a birth certificate or to look among her keepsakes, and have a coughing fit from the aged newspapers. This is close to the process of writing this memoir, for me.

My mother, who read me books every night, taught me, Books open and close and the things inside them stay inside them. At two years old, I had no idea what she was talking about. I scratched and grabbed at the pages of my storybooks, convinced that I could pull the characters off and make them real. I was confused and upset when they didn't jump off the pages to play with me. Half a century later, I still grab at characters, only now, from inside my brain, and I transfer them onto blank white spaces where they can be real again and find you, beautiful Reader.

This book, for me, is one gorgeous rearrangement of all that otherwise would be locked. This memoir, like any other, is about how what we refuse to remember carves us into who we are. I place this book, unlocked and open, spoken and broken, into your hands.

Next page