This is a better book than it started out to be, and I am glad to recognize the generosity of those who helped to improve it. A term of leave permitted me to concentrate on writing the almost-final draft of this book, for which I thank the fiscal powers of the University of Michigan. The Michigan English Department provided a wonderfully stimulating intellectual home during the time I researched and wrote this study, and I am grateful both to my colleagues for their vitality and intellectual engagement and to my students, who always insistently challenge my thinking (if this is not restful, it is nonetheless inestimably helpful). Karla Taylor has been a splendid senior colleague and friend for the past five years, and debating issues and interpretations with her has been great fun; moreover, she cogently critiqued the almost-finished book manuscript and suggested many improvements. Henry Ansgar Kelly, my graduate advisor, also read the book manuscript; his superb eye for detail, his broad learning, and his friendship proved, as always, invaluable. Two anonymous readers wrote very thoughtful reports for the press, giving me much needed and much appreciated perspectives on the argument. I am indeed enriched by being so deeply in debt to so many.

T. L. T.

Afterword

these things are important not because a high-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because they are useful.

Marianne Moore, Poetry

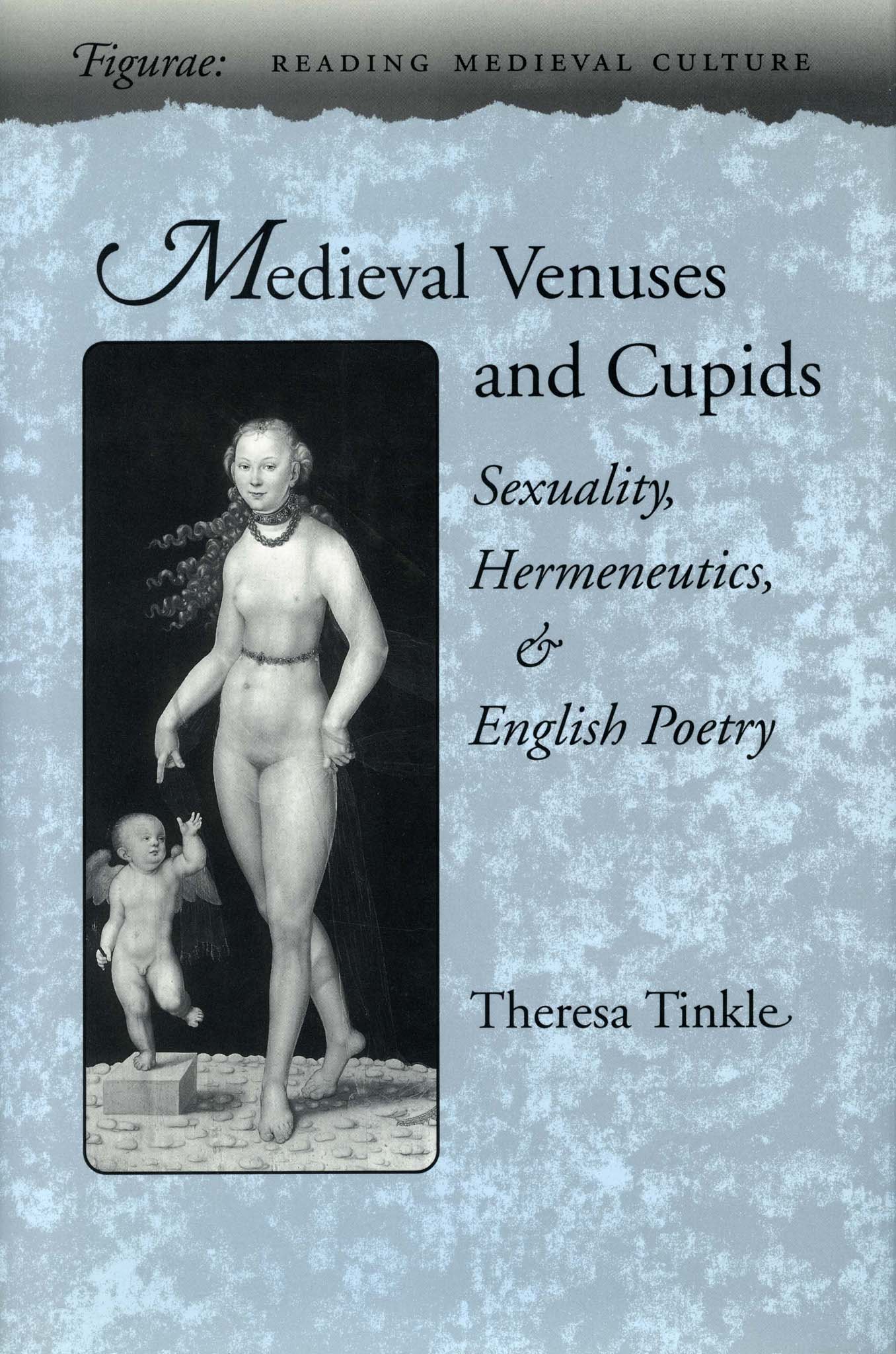

For all the potential interest of mythographic and encyclopedic traditions, the texts that delineate those traditions are very often treated in medieval studies only as positivist sources of accurate historical meaning. Simplified ideas of mythographic two Venuses or moralized Venuses form just a few links in the seemingly endless chain forged by this pervasive critical practice. Over the past few decades, medievalists have fashioned this chain into a bridge across an absolute divide: between canonical, belletristic texts that need interpretation and sensitive attention to nuances, and other texts that offer up transparent, immediately accessible meanings. This is a problematic divide and difficult to justify. Mythographies, like commentary and exegetical traditions, do not yield fixed historical meanings but rather continual renegotiations of meanings; iconography similarly discloses that the extrapoetic is no less ambiguous than the poetic.

Mythographies, like a great deal of other medieval noncanonical and Latin literature, occupy a curious space in medieval studies, a space almost wholly exempt from close critical analysis and from literary theory, which one evidently needs only when reading canonical literature (and especially poetry). Within the most sophisticated theoretical approaches to, for example, Chaucers works, we run across wholly untheorized, positivist, and navely historicist uses of mythography. While there are many untheorized readings, however, there are no untheoretical ones; and this is as true with medieval Latin literature, including encyclopedias, as with a modern novel. The dominant untheorized practice discloses a lack of thoughtfulness that attends naturalized biases against noncanonical other literature. Rather than continuing to handle mythography with a peculiar combination of disdain for its unliterary texture and deference to its authority, we should treat its verbal texture as amenable to critical analysis, and its authority as an always unstable formation, exposed to challenges. Mythographies contain fascinating material, open intriguing questions, and definitely merit further study both for their own sake and in relation to poetry and other genres. That mythography cannot tell us what poetry means does not argue that medievalists should ignore it, commentaries, exegesis, and the like. Instead, we should reexamine these traditions, attending thoughtfully to what they consist of, what they can tell us about medieval habits of reading, what appeal they might hold forth, if not for us personally, then perhaps for someone somewhere in another episteme. If mythographies and commentaries cannot finally tell us the meaning of poetic allusions to mythic figures, birds, beasts, or gems, we may nonetheless gain provocative insights into numerous topics of current interest, such as constructions of sexuality, gender, or hermeneutics. The interest and appeal of any text lies in the critics imagination; the centrality and value of any tradition is what we make of it.

Much as we have made mythography peripheral to the critical enterprise, so have we made ecclesiastical discourses central to the study of medieval sexualities. But no single discourse can possibly elucidate everything about medieval sexuality, no matter how vital or dominant that discourse may have been. Ecclesiastical writing did indeed have profound impact on conceptualizations of sex and sexuality, as on most aspects of medieval culture. Yet if we study ecclesiastical writing in isolation, we are unable fully to detect even the nature of that impact. Sexuality is inscribed in many discourses, and, now that we have studies of some of them, it is perhaps time for us to turn our attention more fully to their interactions, to how they conflict with and complement one another. As we do so, we should remember that each discourse suggests particular and limited points of view, and that each implies its own privileged system of judgment. These discursively bound perspectives often remain segregated from one another, and that is telling; they may also at times be brought into dialogic relations, and that is surely at least as intriguing.

If this book has suggested new ways of engaging and theorizing this kind of interdisciplinary study, new ways of thinking about the relationships between mythography and poetry, about the tensions and ambiguities implicit in medieval sexualities, about the potentially complex quality of poetic allusions to myth, it has fulfilled its most important purposes. In the end, though, the merit of this as of any study is what it permits others to discover, how it encourages others to take the conclusions in directions unimagined by the author. Modern critical discourse shares this at least with medieval mythographies and commentaries: each discourse depends on the continual appropriation of interpretive paradigms for new purposes. Writers from Augustine of Hippo and Remigius of Auxerre to Chaucer and Henryson would appreciate the vigorous continuity of the interpretive project.

Reference Matter

Notes

INTRODUCTION

Because I do not later develop this identification in any detail, it seems only fair to refer the reader to those who do: Woolf, English Religious Lyric , 16567; and Robert Taylor, Figure of Amor, 31011.

Seznec, Survival of the Pagan Gods; Tuve, Allegorical Imagery ; Allen, Friar as Critic. One could also consult any reliable classical dictionary to gain a sense of just how complex and confused the ancient figures are: e.g., Lemprieres Classical Dictionary.

Cadden, Meanings of Sex Difference, argues similarly about related discourses.