Surfaces

Surfaces

A HISTORY

Joseph A. Amato

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BERKELEYLOS ANGELESLONDON

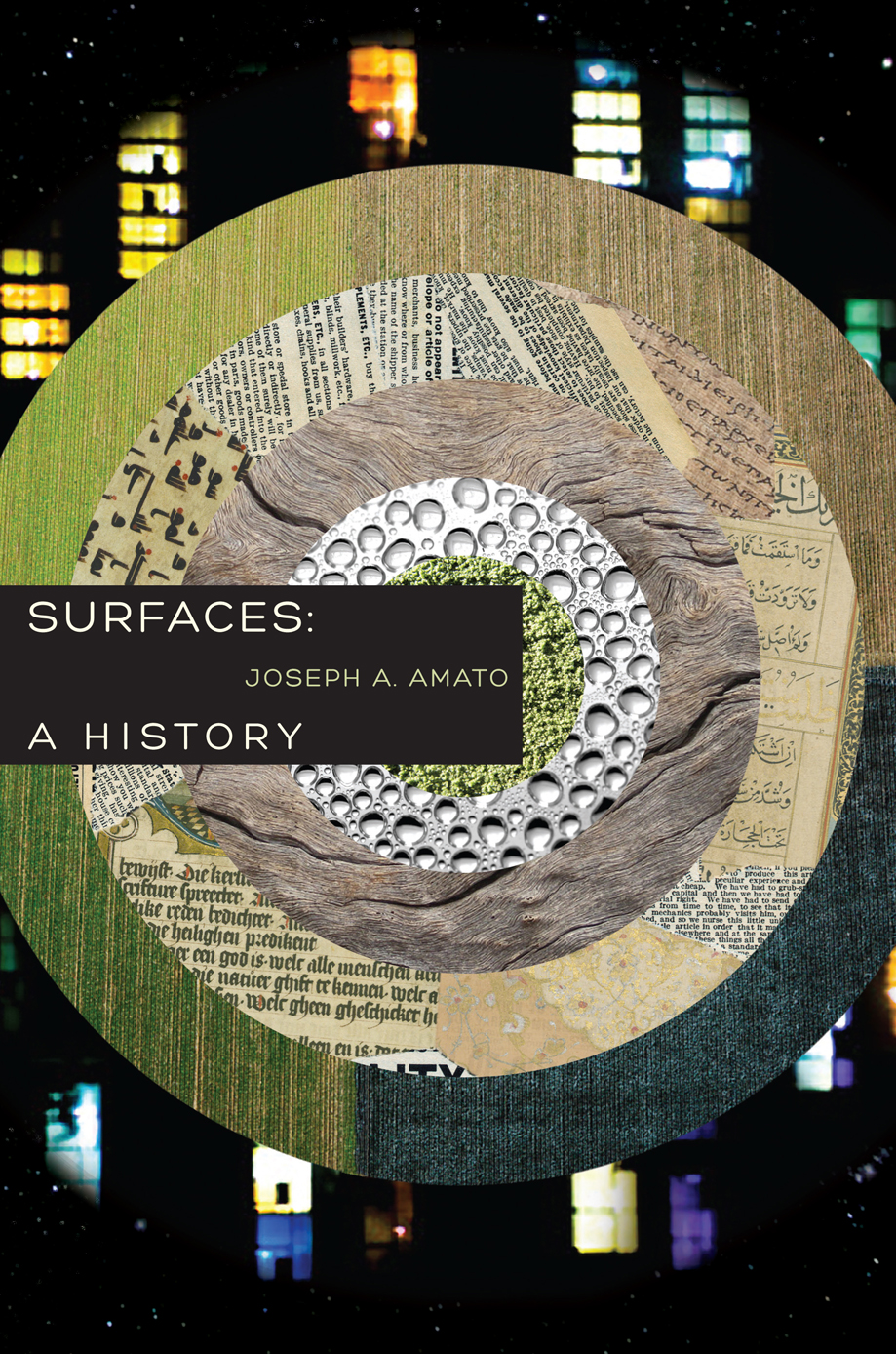

Frontispiece: Surely Joy, by Abigail Rorer, inspired by Henry David Thoreaus poem of that name. Reproduced with the permission of Abigail Rorer, Petersham, Massachusetts.

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Amato, Joseph Anthony.

Surfaces : a history / Joseph A. Amato.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-520-27277-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780520954434

1. Environmental psychology. 2. Perception. 3. Science

Philosophy. I. Title.

BF353.A43 2013

155.91dc232012042651

Manufactured in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Rolland Enviro100, a 100% post-consumer fiber paper that is FSC certified, deinked, processed chlorine-free, and manufactured with renewable biogas energy. It is acid-free and EcoLogo certified.

Cover: Illustrations istockphoto.com.

To Cathy, comfort and spirit of my days

Surely joy

is the condition of life.

Think of the young fry

that leap in ponds,

the myriads of insects

ushered into being

of a summers evening,

the incessant note of the hyla

with which the

woods ring in the spring,

the nonchalance of the butterfly carrying

accident and change painted

in a thousand hues upon his wings,

or the brook minnow stemming stoutly

the current, the lustre of whose

scales worn bright

by the attrition, is reflected

upon the bank.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU , Surely Joy

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

IN THIS BOOK, I EXPLORE OUR RELATION TO SURFACES in order to carry out a historical, philosophical, and anthropological meditation on humans as self-reflecting, self-defining, and self-making creatures. Having written an impressionistic and, I hope, evocative history of microsurfaces in Dust: A History of the Small and Invisible and a history of macrosurfaces in On Foot: A History of Walking, I took a jump: why not write a history of surfaces in general?

Surfaces cradle and nurture our bodies and awaken and define the minds that perceive them. Surfaces direct energy, generate motives, and become ends in themselves. Surfaces shape space; they measure change and reveal movements and motions. They declare in patterns things near, around, and afar. They signal what is, what is leaving and vanishing, and what might be coming. They stretch before us in fields of woven beauty, coherence, and logic, or offer jumbles and thickets that bar order and entrance. They give rise to elemental pairings such as up and down, front and back, around and across, without and within, hot and cold, tight and loose, thick and thin, full and vacant, transparent and opaque, heavy and light, sinking and buoyant. As blatant and blaring as trumpets and as startling as a fresh bank of forsythia in early spring, surfaces declare places and conjure expectations.

Surfaces may be great and bold walls that over time are scored by lines and cracks and splotched with green moss. Surfaces also can be gates and windows. Skins cover interiors, too. Baby skin sets the spirits of the old dancing. Feeling a face, a blind woman reads the lifetime of the person standing before her. A first bulging pimple sets a child with little knowledge of anatomy to pondering the chemistry of his inside. Unconsciously, we forever move back and forth between inner and outer layers. We conjure substances, hear signals, conjugate being, or are filled with unspecified foreboding.

Surfaces, to suggest a general kind of dialectic (though nothing as systematic as Hegels or Marxs), are the topic of this work. They establish the contexts, configurations, and juxtapositions of thing and flesh, nature and society, and they nurture life and awaken the mind. Humans forever and constantly move in and out of the worlds surfaces, traveling between things and objects, the other and the self. Outsides point toward and come to identify insides.

Surfaces arouse and guide animals and human alike. As the fanning movement of a birds colorful tail feathers attracts potential mates, so a single glimpse of Beatrices face won Dantes lifelong devotion and spurred his poetic creations of great refinement. More prosaically, people speak about a subject as being as plain as the nose on their face. They read fate in the lines on their palms, talk about laughing on the outside and crying on the inside, and circle an ear with an index finger to describe the loss of ones inner and outer bearing. Surfaces provide immediate signals, and yet they take on metaphoric meaning. The German word Blatt and, similarly, the Russian word ucm [uct]indicates a page, blade, or leaf, but is also used to describe a plate, a lamina, or a newspaper. The French word taille, a cut or trim of page, also has come to mean an edge, to hew, or the slim figure of une personne bien taille. Our word trim can be used in descriptions of shaping hedges or heads of hair, and we also trim messy budgets and sloppy sails.

Indeed, we construct worlds out of ideas of interrelations, out of the realities of surfaces, spaces, and things. In what has been for me a long-time favorite, the 1958 French classic The Poetics of Space, twentieth-century French philosopher Gaston Bachelard offers an ontological perspective on the space and surfaces of inner worlds.

Moving in approximately the same direction in this work, I go from outer to inner layers of life and thought. In the introductory chapters, I affirm that humans, in our life and as animals, can be understood as a set of surfaces living among other, greater, and more varied sets of surfaces. With special attention to skin and hands, I examine our evolution and development as a consequence of our interactions with both natural and made surfaces. In the following chapters, I take up cities and civilizations as both the result of and laboratories for the making and refinement of surfaces, and I consider how surfaces, through our drawing, writing, sculpture, weaving, pottery, and metallurgy, have become material and symbolic means of self-making and self-definition.

In accord with a phenomenological approach, I suggest that surfaces are transformed from sensations and perceptions into concepts, images, symbols, and language. Surfaces furnish our primary encounters with the outer and the inner layers of thingstheir cover, epidermis, membrane, bark, rind, hide, and skin. They also present us with our first experiences of the primary disposition of objects, bodies, and life out there, beyond us. In other terms, humans, ourselves a body of surfaces, meet and interact with a world dressed in surfaces. Surfaces are the wardrobe of being. They present the world as animate and inanimate, as parts and wholes, as singularities and particularities, and also as faces and Gestalts of selves, others, animals, objects, places, situations, and whole horizons. On the largest scale, surfaces form and are organized into, to draw upon Clive Gambles Origins and Revolutions, a series of scapes: bodyscapes, soundscapes, mindscapes, taskscapes, landscapes, and sensescapes.

Next page