Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

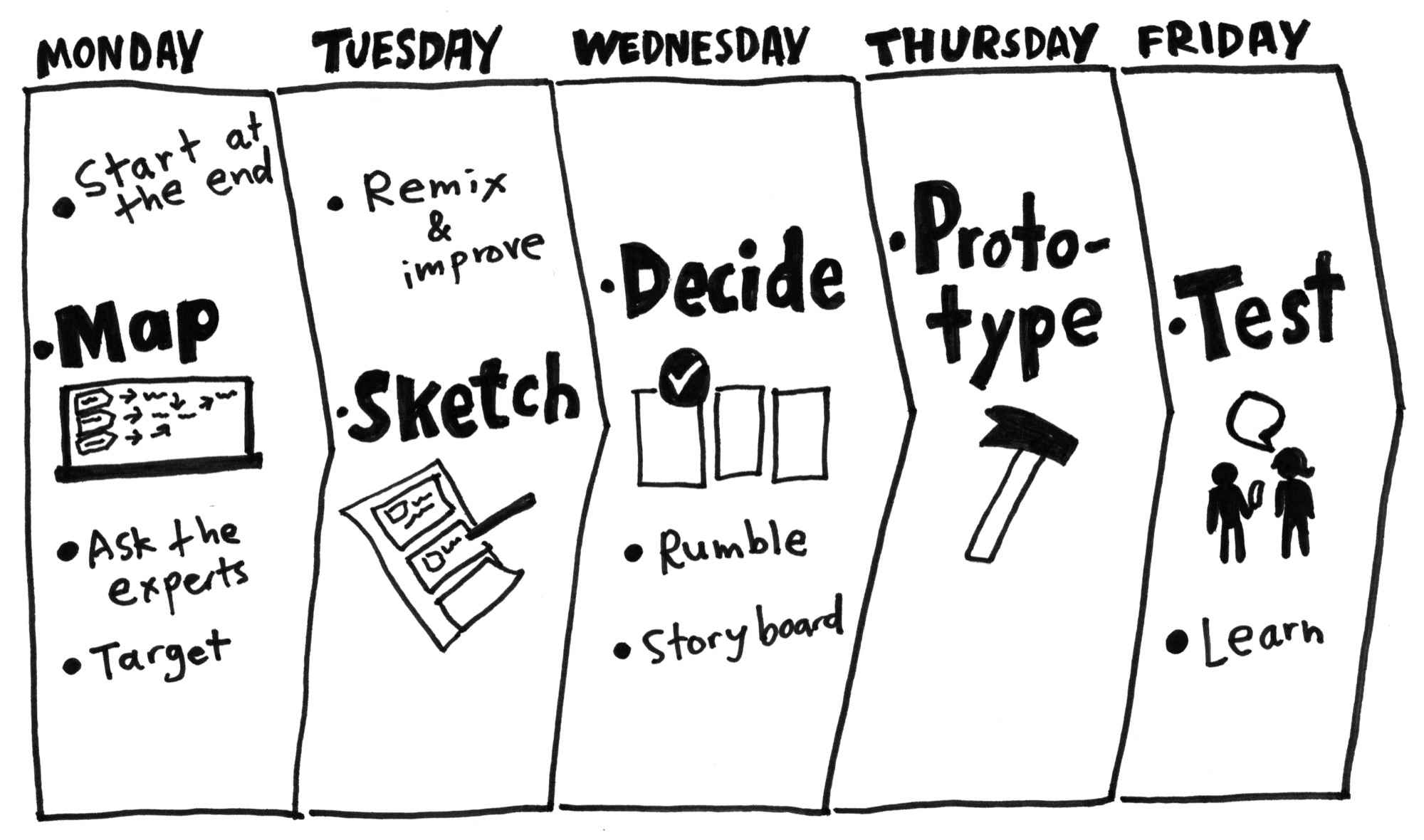

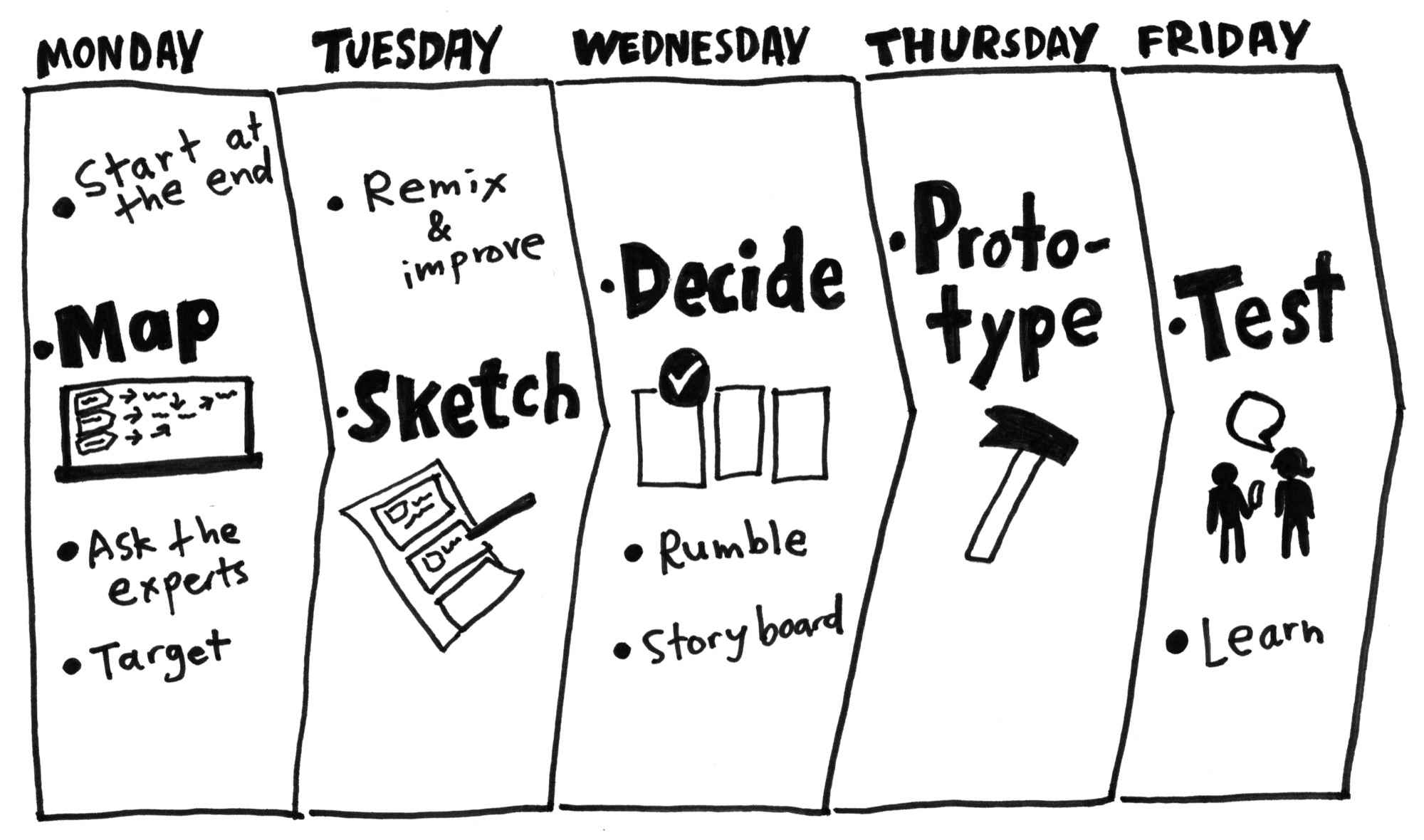

Start with a big problem

Get a Decider, a Facilitator, and a diverse team

Schedule five days and find the right room

Agree to a long-term goal

Diagram the problem

Interview your teammates and other experts

Choose a focus for your sprint

Look for old ideas and inspiration

Put detailed solutions on paper

Choose the best solutions without groupthink

Keep competing ideas alive

Make a plan for the prototype

Build a faade instead of a product

Find the right tools, then divide and conquer

Get big insights from just five customers

Ask the right questions

Find patterns and plan the next step

One last nudge to help you start

Jake:

To Mom, who helped me make castles out of cardboard And to Holly, who picked me up when I caught the wrong bus

John:

To my grandpa Gib, who would have bought the first hundred books

Braden:

To my parents, who encouraged me to explore the world and make it better

Preface

What I was doing at work wasnt working.

In 2003, my wife and I had our first child. When I returned to the office, I wanted my time on the job to be as meaningful as my time with family. I took a hard look at my habitsand saw that I wasnt spending my effort on the most important work.

So I started optimizing. I read productivity books. I made spreadsheets to track how efficient I felt when I exercised in the morning versus at lunchtime, or when I drank coffee versus tea. During one month, I experimented with five different kinds of to-do lists. Yes, all of this analysis was weird. But little by little, I got more focused and more organized.

Then, in 2007, I got a job at Google, and there, I found the perfect culture for a process geek. Google encourages experimentation, not only in the products, but in the methods used by individuals... and teams.

Improving team processes became an obsession for me (yes, weird again). My first attempts were brainstorming workshops with teams of engineers. Group brainstorming, where everyone shouts out ideas, is a lot of fun. After a few hours together, wed have a big pile of sticky notes and everyone would be in great spirits.

But one day, in the middle of a brainstorm, an engineer interrupted the process. How do you know brainstorming works? he asked. I wasnt sure what to say. The truth was embarrassing: I had been surveying participants to see if they enjoyed the workshops, but I hadnt been measuring the actual results.

So I reviewed the outcome of the workshops Id run. And I noticed a problem. The ideas that went on to launch and become successful were not generated in the shout-out-loud brainstorms. The best ideas came from somewhere else. But where?

Individuals were still thinking up ideas the same way they always hadwhile sitting at their desks, or waiting at a coffee shop, or taking a shower. Those individual-generated ideas were better. When the excitement of the workshop was over, the brainstorm ideas just couldnt compete.

Maybe there wasnt enough time in these sessions to think deeply. Maybe it was because the brainstorm ended with drawings on paper, instead of something realistic. The more I thought about it, the more flaws I saw in my approach.

I compared the brainstorms with my own day-to-day work at Google. My best work happened when I had a big challenge and not quite enough time.

One such project happened in 2009. A Gmail engineer named Peter Balsiger came up with an idea for automatically organizing email. I got excited about his ideaknown as Priority Inboxand recruited another engineer, Annie Chen, to work on it with us. Annie agreed, but she would only give it one month. If we couldnt prove that the idea was viable in that time, shed switch to a different project. I was certain that one month wasnt enough time, but Annie is an outstanding engineer, so I decided to take what I could get.

We split the month into four weeklong chunks. Each week, we came up with a new design. Annie and Peter built a prototype, and then, at the end of the week, we tested the design with a few hundred people.

By the end of the month, we had struck on a solution that people could understandand wanted to use. Annie stayed on to lead the Priority Inbox team. And somehow, wed done the design work in a fraction of the usual time.

A few months later, I visited Serge Lachapelle and Mikael Drugge, two Googlers who work in Stockholm. The three of us wanted to test an idea for video meeting software that could run in a web browser. I was only in town for a few days, so we worked as fast as we could. By the end of the visit, we had a working prototype. We emailed it to our coworkers and started using it for meetings. After a few months, the whole company was using it. (Later, a polished and improved version of that web-based app launched as Google Hangouts.)

In both cases, I realized I had worked far more effectively than in my normal daily routine or in any brainstorm workshop. What was different?

First, there was time to develop ideas independently, unlike the shouting and pitching in a group brainstorm. But there wasnt too much time. Looming deadlines forced me to focus. I couldnt afford to overthink details or get caught up in other, less important work, as I often did on regular workdays.

The other key ingredients were the people. The engineers, the product manager, and the designer were all in the room together, each solving his or her own part of the problem, each ready to answer the others questions.

I reconsidered those team workshops. What if I added these other magic ingredientsa focus on individual work, time to prototype, and an inescapable deadline? I decided to call it a design sprint.

I created a rough schedule for my first sprint: a day of sharing information and sketching ideas, followed by four days of prototyping. Once again, Google teams welcomed the experiment. I led sprints for Chrome, Google Search, Gmail, and other projects.

It was exciting. The sprints worked. Ideas were tested, built, launched, and best of all, they often succeeded in the real world. The sprint process spread across Google from team to team and office to office. A designer from Google X got interested in the method, so she ran a sprint for a team in Ads. The Googlers from the Ads sprint told their colleagues, and so on. Soon I was hearing about sprints from people Id never met.

I made some mistakes along the way. My first sprint involved forty peoplea ridiculously high number that nearly derailed the sprint before it began. I adjusted the amount of time spent on developing ideas and the time spent on prototyping. I learned what was too fast, too slow, and finally, just right.

A couple of years later, I met with Bill Maris to talk about sprints. Bill is the CEO of Google Ventures, a venture capital firm created by Google to invest in promising startups. Hes one of the most influential people in Silicon Valley. However, you wouldnt know it from his casual demeanor. On that particular afternoon, he was wearing a typical outfit of his: a baseball hat and a T-shirt that said something about Vermont.