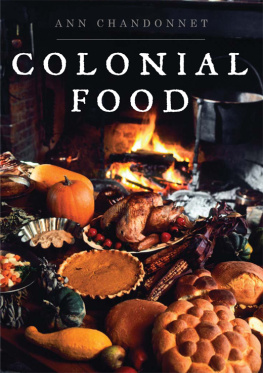

COLONIAL FOOD

Ann Chandonnet

Dried britches beans hang both to the right and the left of the cobblestone fireplace in this colonial cabin in Tennessee. Beside the hearth is a low chopping block, made from a stump. On the table is a wooden dough-rising bowl.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

The kitchen of the Ximenez House in St. Augustine, Florida, was well equipped for elegant meals. The table holds a spice box with six lidded compartments. Sugar nippers were used to bite sweet bits from the hard, white cone (the form in which sugar was sold until the early nineteenth century). The Ximenez-Fatio House is owned by The National Society of the Colonial Dames in the State of Florida.

CONTENTS

On a bed of stewed greens, roast chicken blanketed with gravy takes center place for dinner, surrounded by individual vegetable fritters. Bread, baked in a clay casserole, has already been sampled.

INTRODUCTION

C OLONIAL FOOD is an introduction to the extraordinary culinary transformation kindled when explorers and colonists from England, Europe and Russia arrived in North America. Their challenge was to survive in the New World and prepare previously unknown foods like maize, potatoes, tomatoes, chocolate and chilies. Colonial diet was shaped by OldWorld habits, and seeds brought from home, as well as plants harvested in the wild and crops cultivated by Native Americans. American staples like corn (maize), various squashes and beans were quickly accepted by newcomers.

Preparing colonial food was not simply a matter of making new ingredients palatable. It also required a staggering range of skills: chopping kindling, keeping a fire burning indefinitely, plucking feathers from fowl, butchering animals large and small, cosseting bread yeast, brewing beer, making cheese, adjusting burners of coals on a hearth and gauging the temperature of a bake oven. There were related skills, too, such as milking, making soap and candles, grinding corn, fermenting vinegar, pulverizing sugar, drying damp flour and recycling stale bread.

The housewifes universe spiraled out from hearth and barnyard to tending a kitchen garden and perhaps a large vegetable garden, as well as assisting with the grain harvest. Growing and processing flax and hemp might have been counted among her endless chores.

Preserving methods were limited to drying, smoking, pickling and salting, so the cold months of the year saw a more limited diet than warm months. Dried apples and pumpkin were important staples, while sauerkraut and root vegetables like turnips were common winter fare.

In the seventeenth century, the ordinary frontiersman dined chiefly on corn, or Indian, in some formhoe cake, samp, hominy or Hasty Pudding. Ben Franklin discussed the delights of Indian in two essays. Corns flavor, he enthused, is one of the most agreeable and wholesome ... in the world; that its green ears roasted are a delicacy beyond expression; that samp, hominy, succatash, and nokehock, made of it, are so many pleasing varieties.

Samp was a porridge made from beaten or boiled corn. Hominy (from the Algonquian rockahominy) is dry corn with the hull and germ removed, often coarsely ground as in hominy grits. Succatash or succotash (from the Narragansett msickquatash, boiled whole corn kernels) is corn mixed with beans, sometimes enriched with fish. Nokehock was parched corn cooked in hot ashes, then pounded into meal.

Cornmeal mush was seasoned with pork, small game, greens, or pumpkin. Typical meals were mush with cream, oatmeal dumplings and gravy, barley broth, or fried sausage with roasted sweet potatoes. However by the eighteenth century, on thriving plantations and in Virginias colonial capital, Williamsburg, European-trained cooks held sway. Hence, diners grew accustomed to fish in pastry, venison pie, ragout of cucumbers, fried ox tongue and imported tipples.

A nice white gravy over a simple boiled chicken was no longer sufficient for entertaining. The goal was to set a table comparable to Londons best. Among the gentry, hostesses spared no expense.

An open door admits sunlight to a cabins main room. A rope bed takes up one corner. Living, cooking and sleeping in a common space was typical of the seventeenth century.

To preserve them for winter eating, rings of squash dry over an open fire. Photographed at Harts Square, a privately owned colonial village near Hickory, North Carolina.

The Indian corn found by the Pilgrims was various colors, including yellow, blue and red. Each ear bore just eight rows of kernels. After four centuries of horticultural improvement, todays ear has nearly double that.

In this Tennessee cabins fireplace, a wall-mounted swinging iron crane supports a large pot ready for cookingeliminating the danger of stepping into the fireplace. Three cast-iron skillets hang within easy reach.

ARRIVING IN THE NEW WORLD

A FTER Christopher Columbus proved that there was desirable land on the far side of the Atlantic in the last years of the fifteenth century, European countries strove for empire. With guile, enslavement, smallpox and genocide, Columbus conquered the Arawak of the Bahamas, Corts the Aztecs of Mexico and Pizarro the Incas of Peru.

By window light, an interpreter in period costume prepares vegetables and fruits including onions and apples for a seventeenth-century feast in Maryland. Dried garlic flanks the window.

In Alta California and other Spanish colonies, missionaries employed Native Americans to cultivate crops including figs, lemons and oranges.

To encourage colonists the British published a prospectus in 1588, Thomas Harriots A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. Harriot gamely sampled the victuall of the country, of which some forms were very straunge unto us. He mentions provender already knownsuch as cornbut adds others: sassafras, sunflowers, medlar, and sturgeon.

As explorers feverishly pursued precious metals, tasty, nourishing new foods were an afterthought. Columbus, however, had an inkling of their worth. He wrote in his diary: There are trees of a thousand kinds all producing their own kind of fruit, and all wonderfully aromatic; I am the saddest man in the world at not recognizing them, because I am certain that they are all of value.

Next page