AMERICAS FIRST CUISINES

Sophie D. Coe

University of Texas Press

Austin

Copyright 1994 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Fifth paperback printing, 2005

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819.

utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coe, Sophie D. (Sophie Dobzhansky), date Americas first cuisines / Sophie D. Coe. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-292-71159-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. AztecsFood. 2. MayasFood. 3. IncasFood. I. Title.

F1219.76.F67C64 1994

394.1'2'08997dc20

93-8836

Cover illustration: Underworld throne scene from a Maya vase in the Princeton University Art Museum. Drawing by Diane Griffiths Peck. Courtesy Michael D. Coe.

ISBN: 978-1-4773-0970-4 (library e-book)

ISBN: 978-1-4773-0971-1 (individual e-book)

doi: 10.7560/711556

Illustrations

Preface

To begin with a metaphor appropriate to a book about food: If this book is the fruit of much reading, eating, traveling, and studying, then the core of the fruit consists of the six articles, three on Aztec food and three on Inca food, that I published in shorter versions in Petits Propos Culinaires between 1985 and 1991. But the tree that produced the fruit was planted long before that by an extremely gracious letter that I received from the editor of Petits Propos Culinaires, Alan Davidson, in return for what was the most banal of letters subscribing to his then newly founded journal. That directed me from the interest and concern common, one hopes, to all competent family cooks toward a more historical and scientific focus for my efforts. For his friendship and encouragement over the years, I cannot thank Alan enough.

Once the project had taken root, the kindness of many libraries helped it to grow. First and foremost I must thank the library system of Yale University, whose amazing resources never seem to come to an end and which endangers researchers by exposing them to too much material and too many paths to explore, rather than too little and too few. The tolerance and helpfulness of the staff is as boundless as the resources, and I am grateful to them all.

Other libraries that I have consulted must also be acknowledged, including the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, which allowed two total strangers who wandered in off the Piazzetta to read the worlds only surviving copy of the Littera mdata della insula de Cuba de Indie. The Biblioteca Urbaniana, the library of the British Academy, and the Instituto Italo-Latino Americano, all in Rome, introduced me to many of the sources.

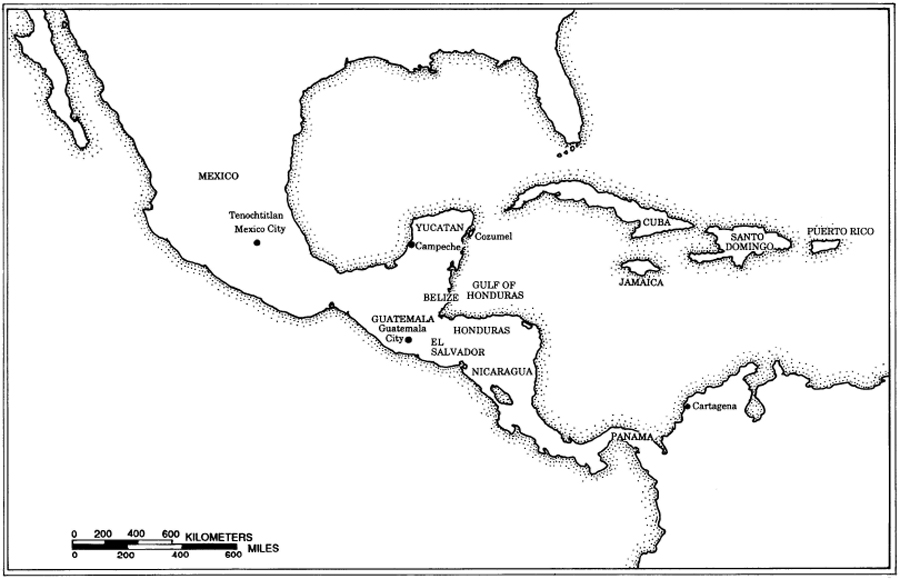

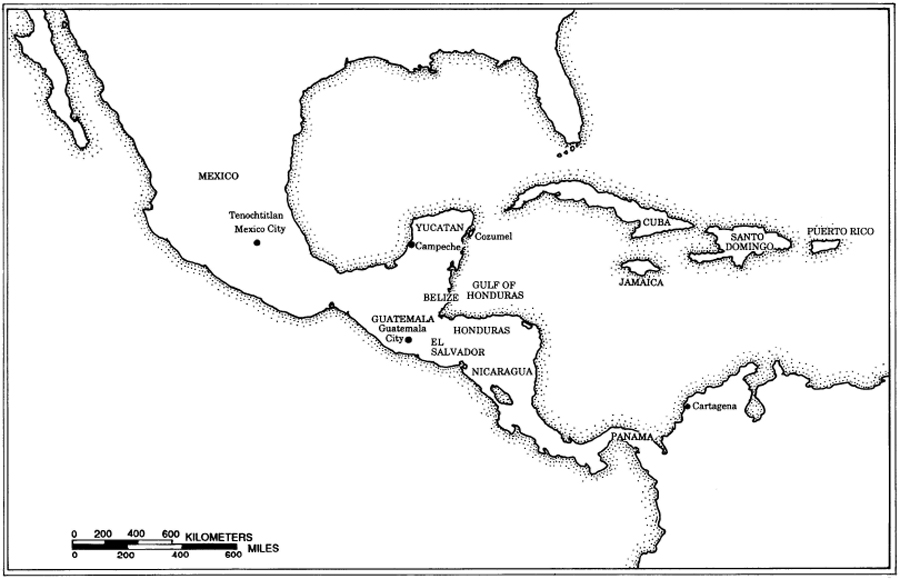

North and Central America. Map by Jean Blackburn.

Many individuals also aided me with advice and comments. From the anthropology department of Yale University they include Floyd Lounsbury, Harold Conklin, and Richard and Lucy Burger. Jos Arrom, professor emeritus of Spanish, was also a great help. R. S. MacNeish and Charles Remington gave advice in their fields of specialization. From other parts of the world David Pendergast, Robert Laughlin, my Harvard thesis advisor Evon Vogt, Payson Sheets, Dennis and Barbara Tedlock, Steve Houston, Karl Taube, Arturo Gmez-Pompa, and Justin and Barbara Kerr all aided my efforts to discover more about the food of the Classic Maya. Doris Heyden and Louise Burkhardt did the same for the Aztecs, and special gratitude is due to Lawrence Kaplan for laying to rest the myth about Pierio Valerio and the beans of Lamon.

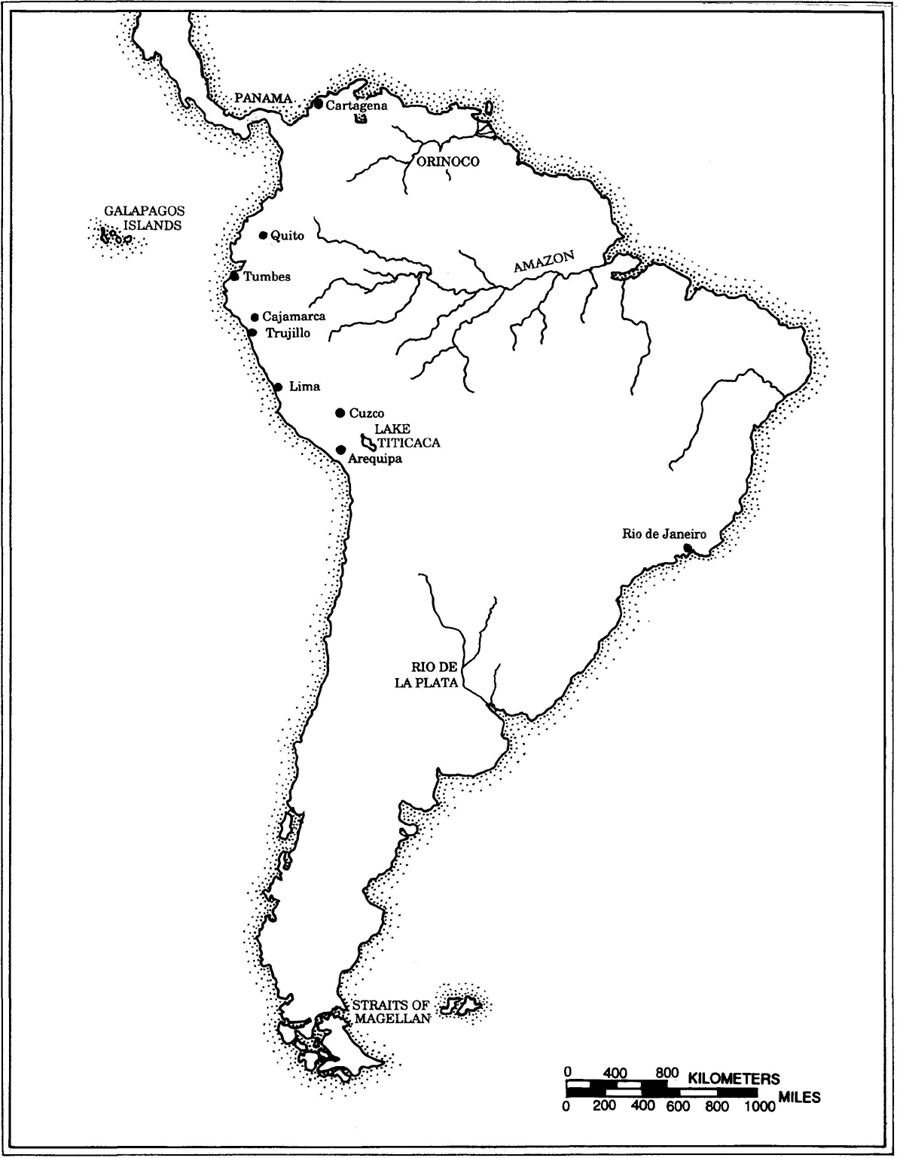

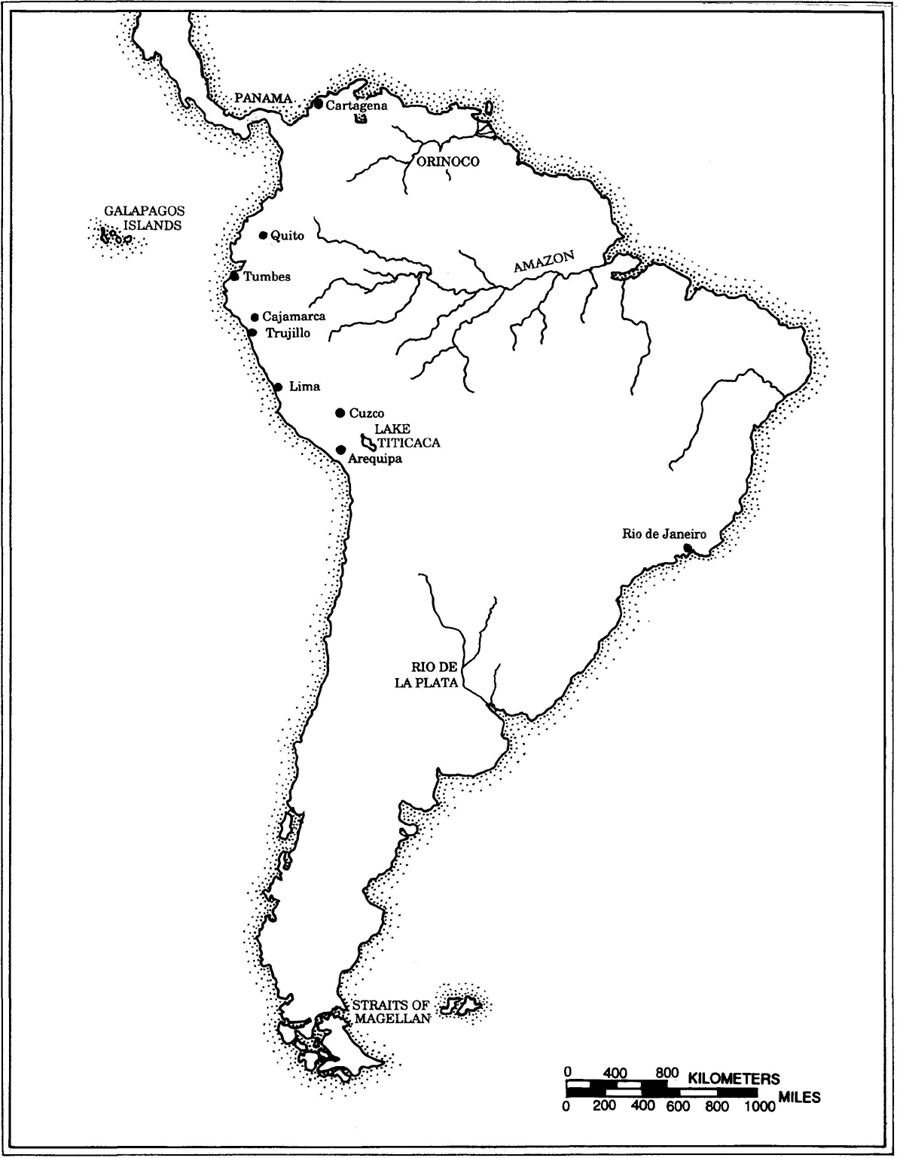

South America. Map by Jean Blackburn.

Many people from other fields added to my knowledge. Jane Buikstra edified me as to the difference between the menu and the ingredients, which I hope will be evident in the pages that follow. My colleagues in the amorphous ranks of food historians also encouraged me with their insights. They are too numerous to mention, but I thank them all.

The translations in the pages that follow are my own, and I am of course responsible for any errors. The only exceptions are the translations by others from Nahuatl, which were checked by my resident Nahuatlato, Michael Coe, and corrected if he thought it necessary. The botanical names have been checked with Mabberley (1989).

And the first shall be the last. More than anyone else, I must thank my husband, Michael Coe, who over the years has seen his treasured library ravaged, his dinners disrupted, and his wife either absent or absent-minded. To him, for all his interest, encouragement, and every other possible sort of assistance, this book is dedicated.

Introduction

This is a book written to celebrate the contribution made by the original inhabitants of the New World, the American Indians, Native Americans, or whatever you wish to call them, to the food of the contemporary world. Their gifts, like this book, can be divided into two parts. The first part of the book deals with the contributions of the New World, the ingredients which the original inhabitants gathered, domesticated, and ate for many millennia before Europeans ever laid eyes on them. This section touches the disciplines of botany and zoology, as it explores the wild flora and fauna from which New World plants and animals were selected for the ultimate benefit of all humanity. There are brief biographies of some of the more important New World crop plants, sketching, insofar as is known, the history of their adoption by small groups of ancient gatherers, then tracing their expansion over climatically suitable areas of this continent and their eventual conquest of the entire globe.

The second portion of the American contribution constitutes the second half of the book. This is concerned with the uses to which these ingredients were put, both the major ones that got the biographies in the first part and the vast gamut of minor actors that had only more local distinction. In other words, I move from the ingredients to the menus in which they were employed. Where data are available, I try to expand the scope of investigation to cover the whole constellation of beliefs, manners, and customs with which all human beings surround their nourishment.

To do this I must use the contemporary accounts of the first meetings of the Europeans with the three high cultures of aboriginal America, the Aztec, the Maya, and the Inca, and try to winnow from them something about the food these people ate. The reason for the choice of these three is simple: that is where the information is. For these people there are available descriptions of food preparation techniques, methods of preservation, and even the ever-elusive recipes, as well as the manner of serving the food and the etiquette of eating it. Unfortunately, and probably due in large part to the absence of female writers, this evidence can also be sparse and scattered, although there were luckily some male writers who were sufficiently concerned with food matters to record them for us.

As a conclusion I give a similar description of the food of the Spaniards in the New World, during the first few decades following the conquests. That earliest infancy of the hybrid cuisine of the modern world, with its attendant loss and tragedy as well as victory and profit, will stand for the mixture of good and evil that the discovery of the New World brought to the world.

Next page