Series Editor: Andrew F. Smith

EDIBLE is a revolutionary new series of books dedicated to food and drink that explores the rich history of cuisine. Each book reveals the global history and culture of one type of food or beverage.

Joseph M. Carlin Curry Colleen Taylor Sen Dates Nawal

F. Smith Herbs Gary Allen Hot Dog Bruce Kraig Ice Cream

Laura B. Weiss Lemon Toby Sonneman Lobster Elisabeth

M. Rogers Potato Andrew F. Smith Rum Richard Foss

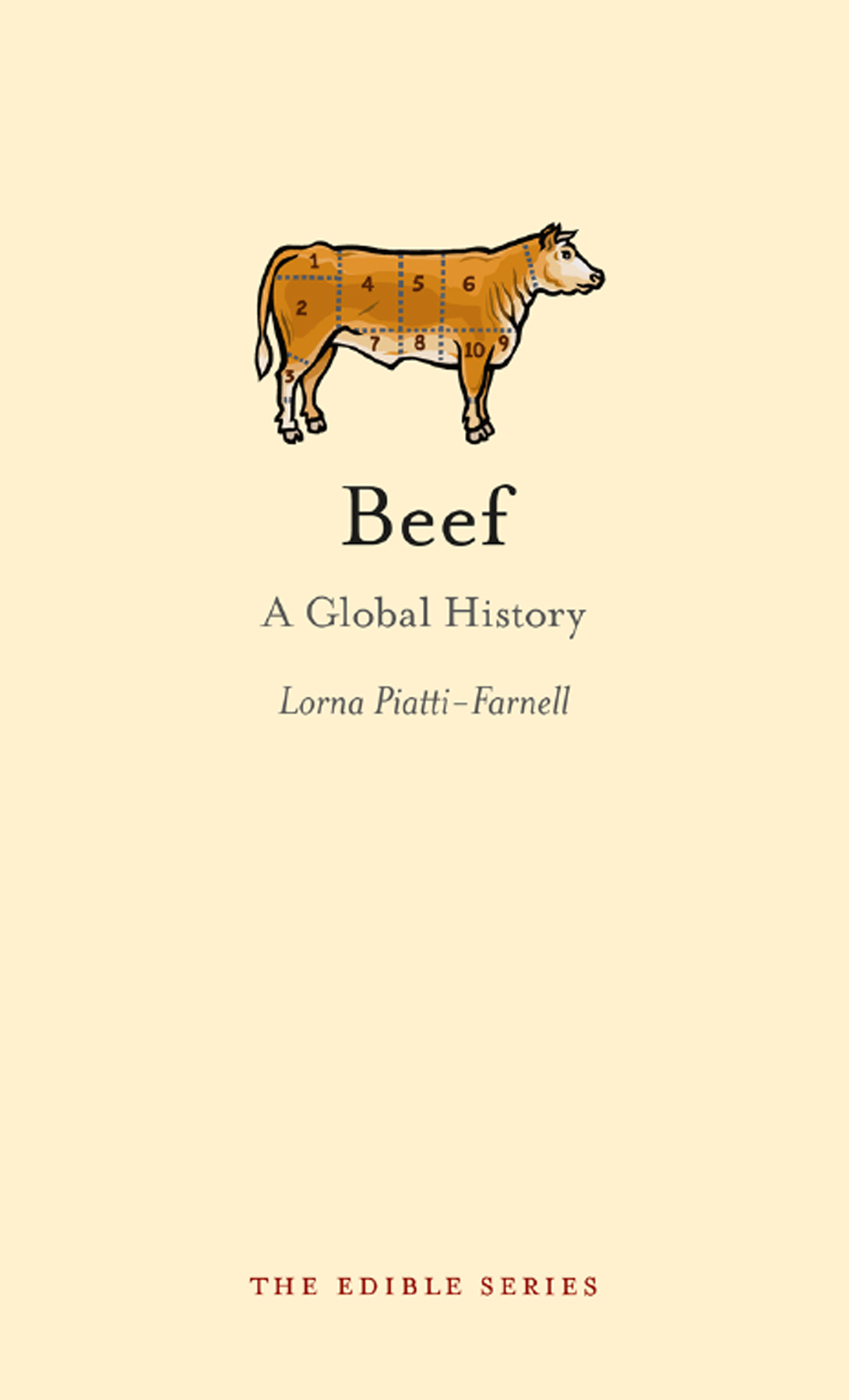

Beef

A Global History

Lorna Piatti-Farnell

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2013

Copyright Lorna Piatti-Farnell 2013

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Piatti-Farnell, Lorna, 1980

Beef: a global history. (Edible)

1. Beef 2. Beef industry 3. Cooking (Beef).

I. Title II. Series

641.362-DC23

eISBN: 9781780231174

Contents

1

Of Beef and Cattle

The history of beef is, to some extent, the history of human civilization. Beef also known as Bos domesticus takes us back to the dawn of human evolution and the consumption of this particular meat has been intertwined with the history of mankind around the world. In prehistoric times, our ancestors were known to have hunted aurochs, a type of wild and rather ferocious cattle that were also the ancestor to modern livestock. Now extinct, auroch bulls are said to have reached a height of 1.8 metres (6 feet), while cows were considerably smaller, reaching only 1.5 metres (5 feet) in height. Cave paintings from several regions in Western Europe depicting detailed hunting scenes testify to the importance of the aurochs to prehistoric Homo sapiens, as the meat from these animals represented a large amount of the food rations within hunter-gatherer tribes.

Indeed, it seems virtually impossible to discuss the global history of beef without first talking about cows. This animal has had such an impact on human societies and cultures over millennia, that its ultimate transformation into beef seems hardly a point of departure. The domestication of cattle was not just a matter of food; it also had an impact on human evolution. Many archaeological and anthropological perspectiveshave emphasized different aspects of how cows transformed human existence. Domestication as such occurred in human organizations 12,000 years ago and primarily concerned small animals such as goats, sheep and pigs. Evidence of the domestication of cattle, however, is present from 8000 BC onwards. The Fertile Crescent encompassing ancient Mesopotamia and now identified with a large area of the Middle East has often been credited as the place of origin for cattle domestication. Nonetheless, the act in itself, and the consequent consumption of beef that derived from it, has been documented throughout history in a myriad of civilizations. And as far as hunter-gatherer communities were concerned, the domestication of cattle changed things drastically and permanently. Once cows were domesticated, and agriculture flourished as a result, the way of the hunter-gatherer ceased to be. For the most part, humans abandoned their nomadic existence and began to live in organized tribes. Cattle were raised for their meat; this was the beginning of what I like to refer to as beef and all that the definition entails.

Prehistoric depictions of aurochs, from a cave painting in Lascaux, France.

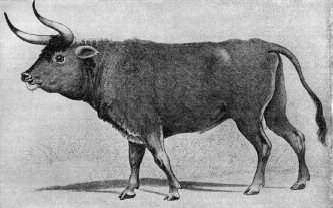

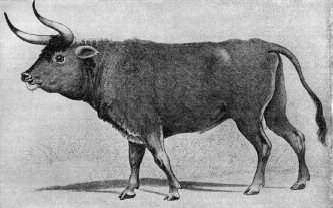

A modern rendition of the prehistoric auroch.

However, and in spite of the fact that signs of cattle domestication are present independently in the prehistoric histories of several countries around the world, the exact reasons that spurred early humans to approach the vicious wild aurochs are unknown. Indeed, humans are known to have dealt with cattle across the globe, developing their ideas on domestication in completely separate circumstances; the presence and consumption of cattle in prehistory has been documented from the southeastern Sahara in Africa to the Indus Valley (an area now part of modern Pakistan). And yet, in archaeological terms, the reasons behind early attempts at domesticating wild cattle for food, while our ancestors had already ample access to domesticated goats and sheep, are still open to debate.

A likely explanation that has been widely developed in the last two centuries by archaeologists and anthropologists alike seems to have a spiritual foundation at its heart. The attraction that the prehistoric cattle exercised on our early ancestors clearly went beyond their perspective potential as food. In 1896, anthropologist Eduard Hahn already presupposed that, as far as the human relationship with first wild and later domesticated cattle was concerned, the connection was reliant on the symbol of the moon, already an emblem of fertility in 7000 BC. Hahn contended that the distinctively curved shape of the cattles horn was reminiscent of the moons nascent crescent, inspiring early humans to associate with the animals on a more permanent basis. In the Cambridge World History of Food (2001), Kenneth Kiple and Kriemhild Cone Ornelas also contend that the wild aurochs were specifically domesticated with religious purposes in mind, as their milk (and later meat) was perceived to be a ritual gift from the goddess. Indeed, the ritualistic and spiritual value of cows remained strong for centuries, if not millennia, as examples of sacred cows and revered oxen often perceived as incarnations of deities can be identified in the religious systems of several ancient civilizations and modern nations, ranging from Europe, to Africa and the Middle East. The most prominent example of this is of course India, where Hinduism perceives cows as sacred and, as historian Hannah Velten points out, mothers of the Universe, associated as they are with the goddess Prithvi. India has the largest concentrated population of cows in the world; unsurprisingly, however, and in virtue of their religious associations, the slaughter and consumption of cattle is forbidden in most areas of the country. Indeed, the consumption of beef seen as an abomination by most strands of Hinduism has formed one of the building blocks for the longstanding rivalry with and dislike of neighbouring Muslim and beef-eating cultural factions, now mainly residing in Pakistan.