ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sources for many of the photographs contained herein include the Archives of the Big Bend and Museum of the Big Bend at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas; Marfa and Presidio County Museum and Marfa Public Library in Marfa, Texas; and the National Park Service, Big Bend National Park. Very special thanks go to the families who not only have donated photographs but also have shared their most intimate family histories and related their family stories. We are most grateful to Louisa Franco Madrid, Antonio Franco, Genoveva Ramrez Rodrguez, Celestina Valenzuela, Juan Manuel Casas, and Maria Zamarrn Bermdez for these contributions. Special appreciation goes to Jack Burgess for many of the mining-related images and to Rush Warren for access to some of these mining sites.

Also, the last-minute and short-deadline contributions by several need to be mentioned here. For their contributions to the chili cook-off segment, thanks go to Melanie Levin, Kathleen Tolbert Ryan, and Steve Tremayne of the Frank X. TolbertWick Fowler Chili Cook-off and Kris Hudspeth and Jennifer Sherfield of the Chili Appreciation Society International Inc. cookoff. Louisa Franco Madrid and Antonio Franco stood by me until the very last day of editing. Juan Manuel Casas also contributed significantly at that point. Carolyn and Jim Burr, Marcos Paredez, Beth Garca, Mike Long, and Crystal Marks were also good friends and contributors. Many others, too many to mention, are credited beneath their photographs.

Scarlett Wirt deserves a special mention for working patiently with everyone after co-author Bob Wirts passing and for donating all of Bobs research data to the cause. Thank you especially, Scarlett, and to Bob, wherever your soul resides, blessings and peace, my friend. We will do our best to continue your legacy.

The most gratitude cannot be adequately expressed, and it goes to my wife, Betty Alex, whose tolerance of my idiosyncrasies and moodiness during this process comes from her dedication and patience. Betty has lived in an unfinished house, stumbled over partially finished walkways, and allowed me the time and space to complete this tome. I am most grateful to this blessed woman. She is also my best critic and editor.

The remaining thanks go to all the people who made Terlingua what it once was and what it is today. Peace to all.

DISCOVER THOUSANDS OF LOCAL HISTORY BOOKS

FEATURING MILLIONS OF VINTAGE IMAGES

Arcadia Publishing, the leading local history publisher in the United States, is committed to making history accessible and meaningful through publishing books that celebrate and preserve the heritage of Americas people and places.

Find more books like this at

www.arcadiapublishing.com

Search for your hometown history, your old stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burcham, W.D. Quicksilver in Terlingua, Texas. Engineering and Mining Journal 103, January 13, 1917: 97.

. Report on the Mariscal Mercury Mine. Unpublished manuscript on file, Big Bend National Park, Texas, August 24, 1936.

Hawley, C.A. Life Along the Border. Spokane, WA: Shaw & Borden Co., 1955.

Madison, Virginia. The Big Bend Country of Texas. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1955.

Phillips, William B. Condition of the Quicksilver Industry in Brewster County, Texas. Engineering and Mining Journal, October 6, 1904: 37679.

. Condition of the Quicksilver Industry in Brewster County, Texas. Engineering and Mining Journal, November 20, 1909: 1,02224.

Ragsdale, Kenneth Baxter. Quicksilver: Terlingua and the Chisos Mining Company. College Station, TX: Texas A&M Press, 1976.

Schuette, C.N. Quicksilver, Bureau of Mines Bulletin 335. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, 1931.

Tolbert, Frank X. A Bowl of Red. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2002.

Walthall, Harris. Harris Walthall Collection. Resources Management History File. Big Bend National Park.

www.abowlofred.com

www.chili.org

Yates, Robert G., and George A. Thompson. Geology and Quicksilver Deposits of the Terlingua Mining District. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1959.

. The Mariposa Mine, Terlingua Quicksilver District, Brewster County, Texas. USGS Open-File Report, 1944: 4475.

. Geologic maps and sections, Study Butte Mine, Terlingua quicksilver district, Brewster County, Texas. USGS Open-File Report, 1966: 66156.

One

MINES

Between 1903 and 1907, a rush of prospectors and developers descended on the area, and the Marfa and Mariposa Mining Company, Texas Almaden Mining Company, and Big Bend Cinnabar Mining Company established major operations between California Hill and Study Butte. The earliest location centered on the Mariposa Mine. By 1910, the Mariposa shut down operation, and a few miles to the east, the Chisos Mine became the major producer and remained so until the Chisos Mining Company went bankrupt in 1937. As the Chisos Mine began successful production in 1903, the Study Butte area was also being prospected and developed by the Texas Almaden and Big Bend Cinnabar Mining Companies. Around 1907, the Lone Star Mine located near the Mariposa also began production. Between California Hill and the Chisos operation was the Colquit-Tigner (Waldron) Mine. The growth and location of Terlingua followed the development of the mining industry and centered for periods where the major production occurred. The earliest location centered on the Mariposa Mine. After the Mariposa shut down, the Chisos Mine assumed the name Terlingua.

There were other mercury-producing districts peripheral to the Terlingua District. The Buena Suerte District consists of the Fresno and Whit-Roy Mines operated at the Contrabando Dome north of Lajitas. The Mariscal Mining District is located about forty miles east and today is within Big Bend National Park. There was also sporadic prospecting around Adobe Walls Mountain, at the Fernandez Mine on the south side of Christmas Mountains, and at Black Mesa north of California Hill.

Between 1941 and 1945, World War II spurred new interest, and the Fresno and Whit-Roy Mines were developed. The Esperado Mining Company reopened the Chisos Mine, but by 1947, all mines in the district were closed because of falling market prices. Between 1965 and 1973, there were sporadic attempts at production at the Lone Star Mine and by the Diamond Shamrock Corporation at Study Butte and Anchor Mining Company at Fresno Mine.

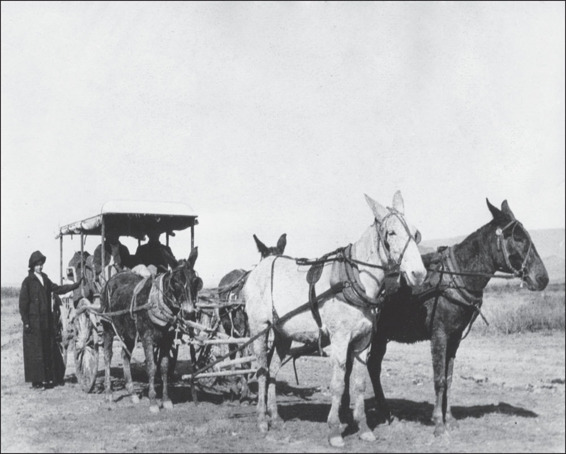

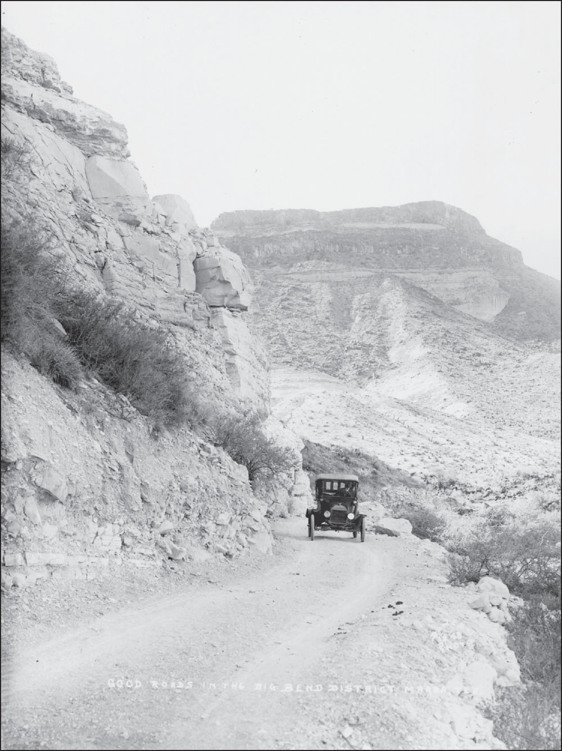

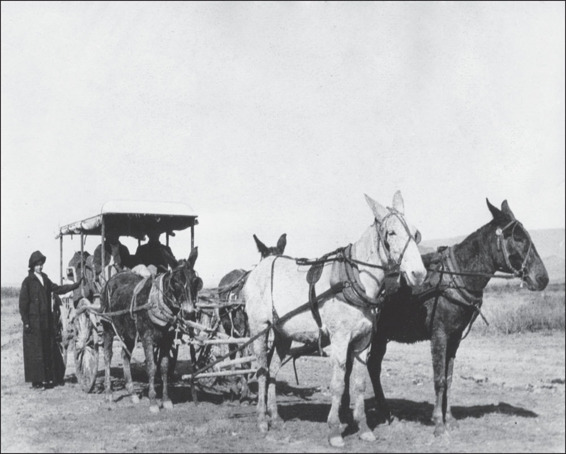

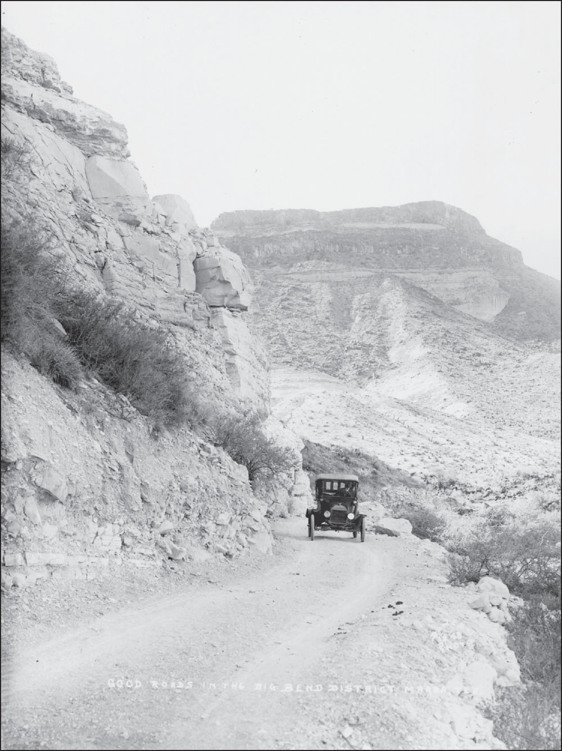

When mining first began in Terlingua, only a few roads reached into the Big Bend area from the train stations of Marfa, Alpine, and Marathon along the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio railroad. One dirt track led south from Marathon to the mining community of Boquillas, Texas, and another ran south from Marfa to the Terlingua area. It took travelers two days riding in a mule-drawn hack to reach the remote area. C.W. Hawley, hired in 1905 as bookkeeper for the Mariposa Mine, devoted two entire chapters in his book Life Along the Border to his excursion in this contraption. The passengers and driver alike packed guns of various kinds, making Hawley wonder what kind of place he was moving to. The road led south to an overnight stop and then went down Fresno Canyon to the small settlement of La Jitas on the Rio Grande before completing the trip at Mariposa. (Photograph from Glenn Burgess collection, courtesy of Jack Burgess.)

Next page