CONTENTS

THE WAYBILL OF THIS BOOK

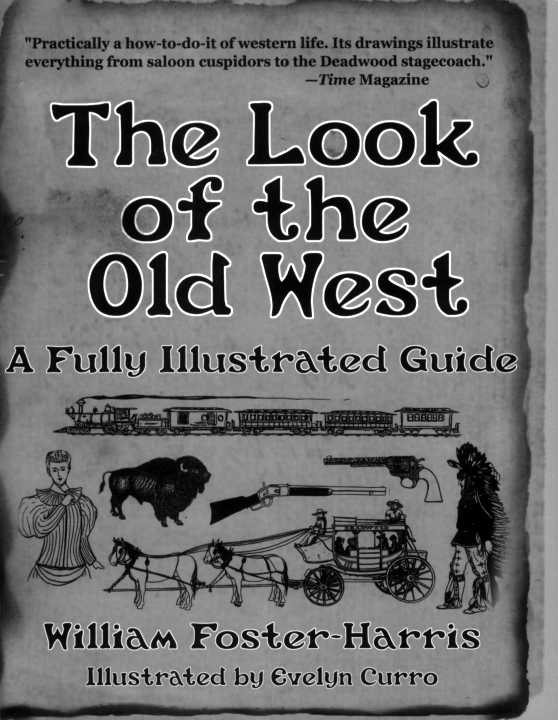

"Perfection," said great old Michelangelo, "is made up of trifles. But perfection is no trifle." Well, here is a book of Western ingredients, the little things which the historians, darn them, generally leave out.

This book tries to cover the real glory years of the Old West, from the Civil War to the Spanish-American conflict and the turn of the century. It tries both to tell you and to show you what the details looked like, what they were named, how they worked, what you did with them-from pistols to pants buttons, from sabers to soup spoons. As you'll appreciate, this is a tall order we've given ourselves, and we've probably made some mistakes, even doing our best. If you catch any, we'd appreciate it if you wrote and told us.

Because, in good part, this is a labor of love. There are worlds and worlds of vital statistics about the West, but just try and visualize a vital statistic) How does it hold its pants up? Does it pack a gun, smoke, chew, wear its hair long, smell sort of peculiar? Sure, this sounds silly, maybe, to a scholar, but when something is really alive in your mind, when you can see it, hear it, and even smell it, these are the tall trifles that perfect the picture. They make it real. And that is the main intent and purpose of this book.

We'll also say it sure took a lot of digging on our part and we hope you like it.

FosTER-HARRIS

EVELYN CURRO

I

SOLDIERS INTO CIVILIANS

"HEN General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox turned from shaking hands with his weeping men, struck his gauntleted fist grimly into his palm, and rode off into immortality, when the blue-clad conquerors converted to Indian fighters, as some of them did, and the defeated grays were about to be civilians again-just what did these seasoned warriors look like?

"HEN General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox turned from shaking hands with his weeping men, struck his gauntleted fist grimly into his palm, and rode off into immortality, when the blue-clad conquerors converted to Indian fighters, as some of them did, and the defeated grays were about to be civilians again-just what did these seasoned warriors look like?

What did they wear? What kind of weapons did they carry? How about their saddles, wagons, books, suspenders, cigars, and all the other details of their paraphernalia? When they went West, as thousands of them did, what did they take with them, and what were the Westerners wearing when they got there? By the eternal, as old Andy Jackson used to say, I like to know!

Here in the spring of 1865 was the supreme turn of American history, the rebirth of a great nation. Here, released, were army corps of some of the fiercest fighting men the world had ever bred. And ready and waiting for them was the wide, wild, and woolly West! The years from 1865 to the turn of the twentieth century were the time of the trail driver, the homesteader, the Indian fighter, the railroad builder. They were the great days that have inspired at least three-fourths of our Western legends and songs, and a multitude of novels, motion pictures, and plays.

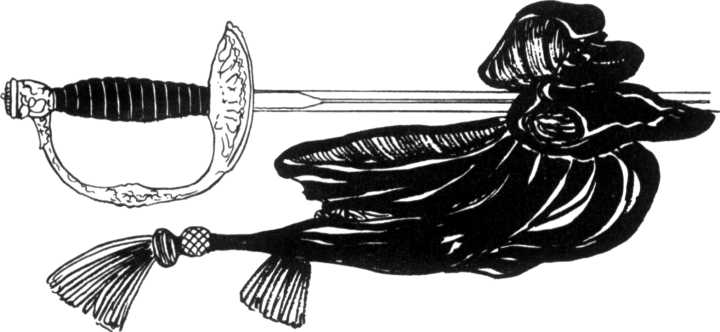

The epoch begins with soldiers. The flavor of the military, Yank and Reb, and the ways of the war are part and parcel of our tale. Soldiers, shedding their blue and gray uniforms (but not all their old Army habits and enmities) to turn back to civilian pursuits; other soldiers still in uniform-or part of a uniformswinging out to chase Indians, guard emigrants, watch over railroad builders, supervise land rushes, man lonely frontier outposts. At the end of the era it was just the other way around: probably there was never a more civilian American army than that rounded up-one can scarcely say mobilized-for the brief war with Spain in 1898.

Yellowleg sergeant

Let's take a look at this human seed stock of the fighting West in 1865. Suppose we start with the cavalry, and, first, the Union cavalryman. The Yellowleg, so called because of the yellow cavalry-color stripes down his breeches seams, was a far cry from his prewar predecessor. He hadn't been too good at first, but four years of furious fighting against the born horsemen of Jeb Stuart, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and such, had made him into a superb warrior, fit match for the red raiders waiting out West.

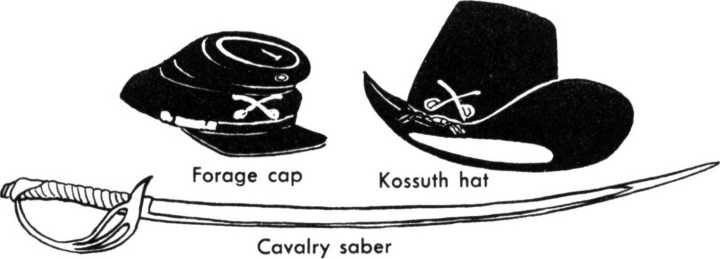

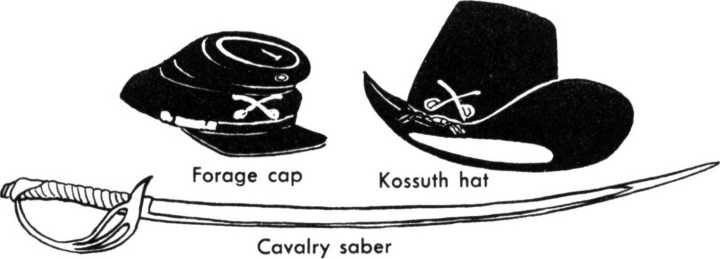

The 1865 cavalryman had two kinds of headgear: a big black "Kossuth" hat; and a forage or fatigue cap, a type that was to characterize our Army for more than forty years. Our trooper had a quaint habit of getting this forage cap a little too small and wearing it right on the top of his head. It had a chin strap to hold it on, a wide leather affair a little different from our modern ones in that it had a brass slide-buckle instead of a leather keeper where the pieces join. And there was quite a bit of history behind this piece of Army headgear.

Napoleon and the great days of the First Empire had greatly influenced American military matters. At the beginning of the war there were entire Union regiments dressed in French uniforms, particularly in the flashy attire of the Zouaves, the French Algerian troops who wore baggy pants, sashes, and braided jackets. These didn't last too long, but the frock coats worn by officers on both sides, the shell jackets, the forage caps, the sleeve insignia worn by Southern officers (galons), even the Union pup tent (tente d'abri ) were all very, very Gallic.

The forage cap was the American version of the French kepi, which in turn had developed from the Napoleonic and earlier shako. A shako (there were some on both sides in the war, by the bye, and the U. S. Infantry returned to them for a while in the seventies) is a stiff, high-crowned cap of leather, felt, or stiffened cloth; and it has a round, flat, hard top, and a cap vizor usually sticking straight out in front. Take the stiffening out of the sides of a shako so that the top flops down toward the front, and you have a kepi. The American Civil War forage caps were made of soft dark blue clothfinished flannel. They had either a flat or a sloping leather vizor. The cap had a wide leather sweatband and was lined with black drill. The troopers were likely to have the down-sloping, rounded style of vizor, which, along with much cloth in the sides of the cap, made up what was popularly known as a "Bummer's cap," the contract style of 1864 that was worn by Sherman's "Bummers" on their march through Georgia. Officers usually had the flatvizored cap, and the round top of the crown ordinarily was braided, something like a modern Marine officer's cap.

"HEN General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox turned from shaking hands with his weeping men, struck his gauntleted fist grimly into his palm, and rode off into immortality, when the blue-clad conquerors converted to Indian fighters, as some of them did, and the defeated grays were about to be civilians again-just what did these seasoned warriors look like?

"HEN General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox turned from shaking hands with his weeping men, struck his gauntleted fist grimly into his palm, and rode off into immortality, when the blue-clad conquerors converted to Indian fighters, as some of them did, and the defeated grays were about to be civilians again-just what did these seasoned warriors look like?