Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Meijer Foundation Fund.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35055-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-35069-1 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226350691.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hirsch, Paul S., author.

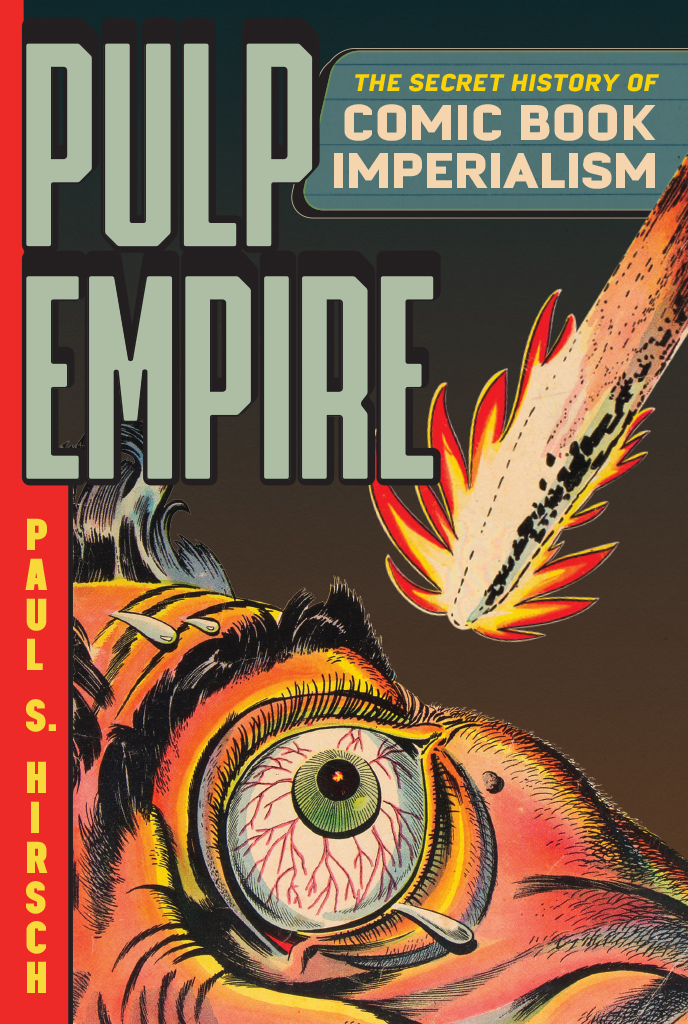

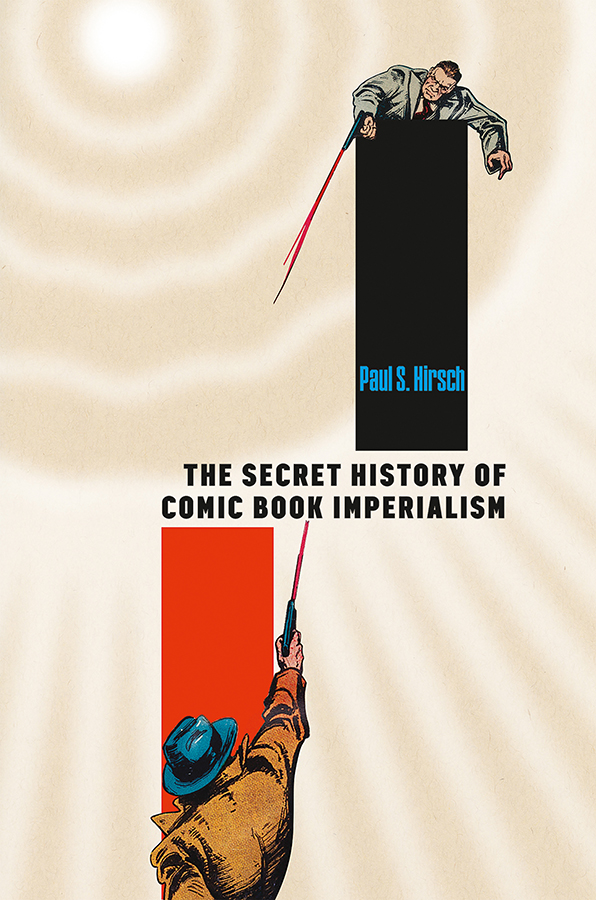

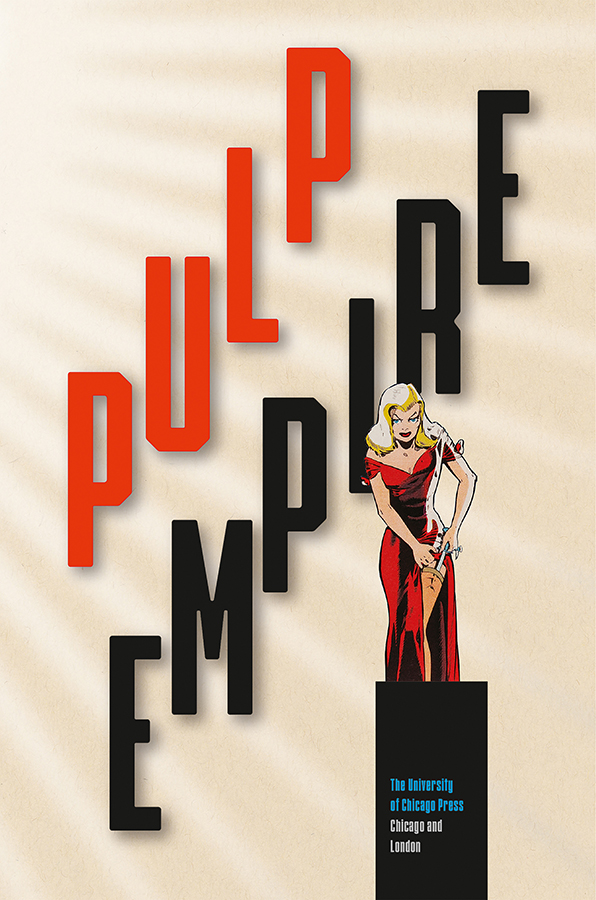

Title: Pulp empire : the secret history of comic book imperialism / Paul S. Hirsch.

Other titles: Secret history of comic book imperialism

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020044646 | ISBN 9780226350554 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226350691 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Comic books, strips, etc.United StatesHistory and criticism. | Comic books, strips, etc.Social aspectsUnited States. | Comic books, strips, etc.Political aspectsUnited States. | Propaganda, American. | Literature in propaganda. | United StatesCivilization1945

Classification: LCC PN6725 .H57 2021 | DDC 741.5/9730904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020044646

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To my familiesthe one I was born to and the others formed from friendship and love

And to Laura Lee and Milomy family, my friends, my more

Contents

Secret Origins

When I was ten years old, a comic book shop owner threatened me with a gun. And it thrilled me.

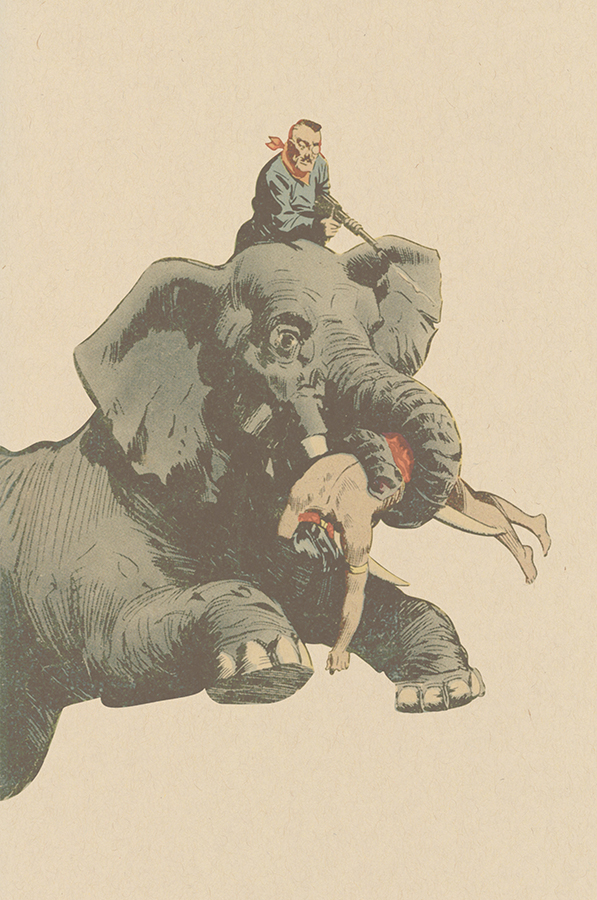

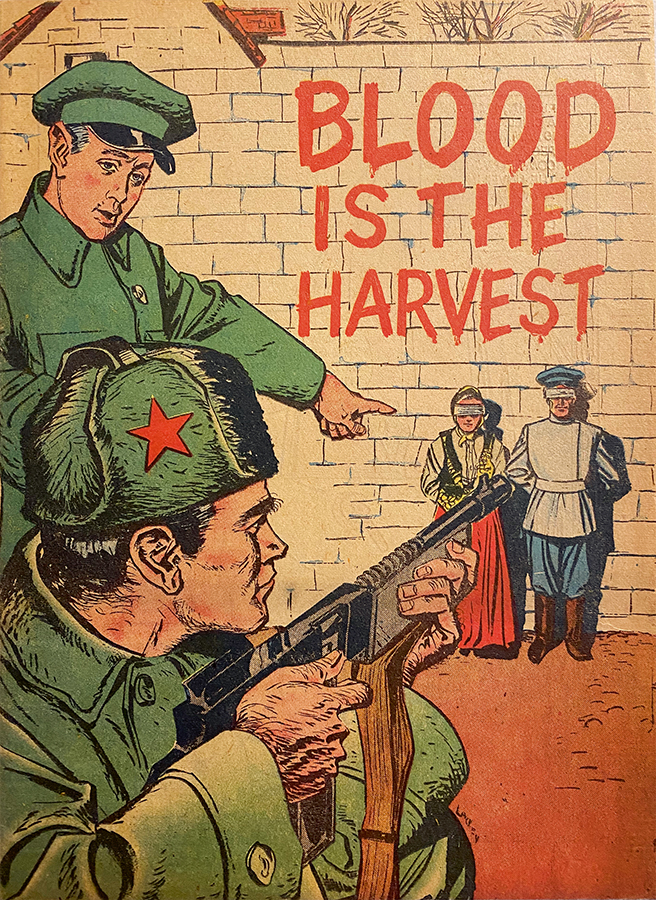

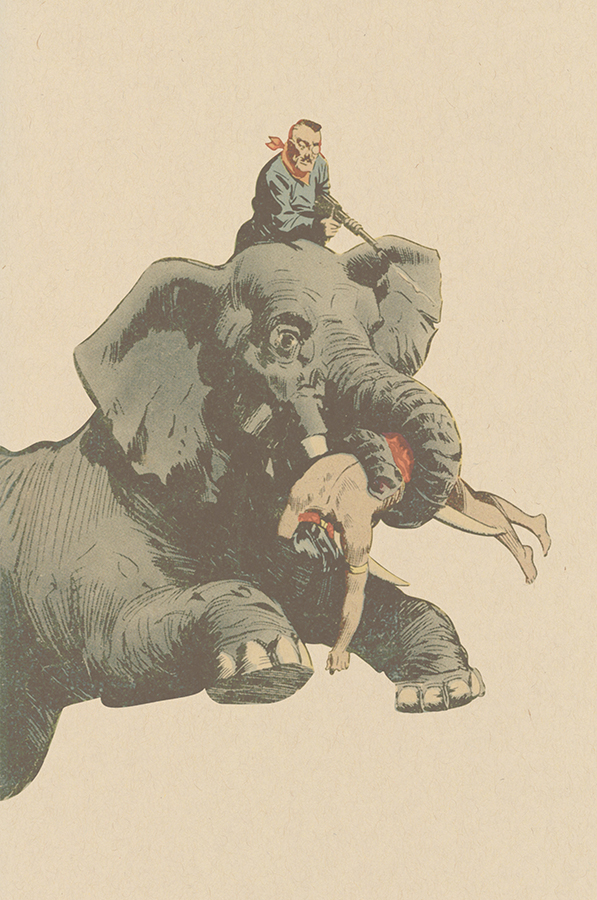

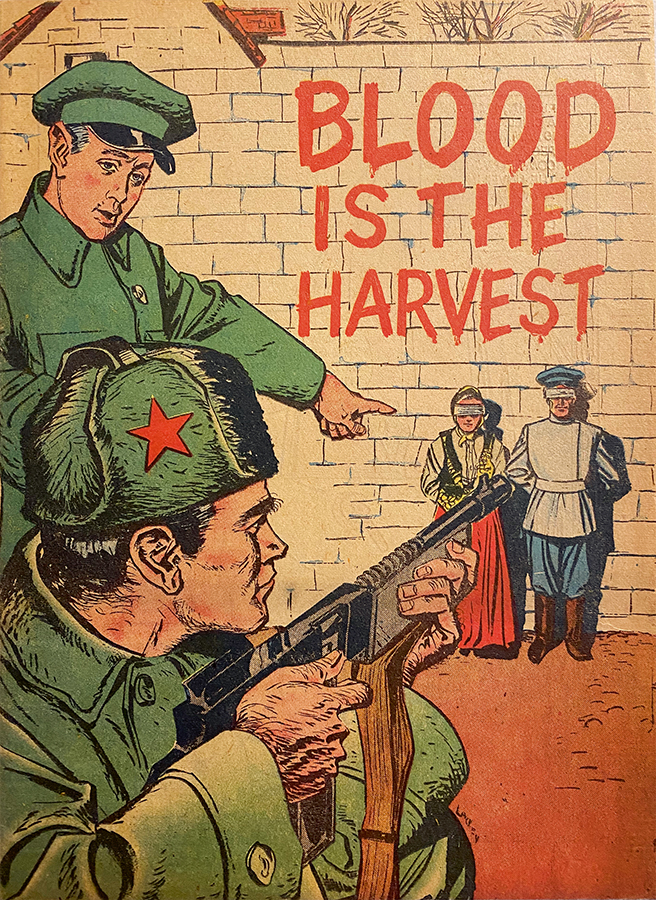

In the mid-1980s, reading and collecting comic books was deeply uncool. Interactions with adults made clear that they deemed my interest distinctly antisocialand they were right. Buying comic books meant walking two miles from my home to a shop in the next town. Wedged between a neon-lit audio store packed with off-brand car stereos and a forlorn florist, it was a narrow, low-ceilinged shop full of long, white cardboard boxes of old comic books. The store stank of musty paper, sweat, and wonderful grease from a nearby pizzeria. The owner, a hostile man whose dark hair hung past a drooping mustache, always worked alone. He perched on a stool behind a tall counter that nearly pinned him to an enormous corkboard on the back wall. On it were mounted rows of expensive, mysterious old comic books like Blood Is the Harvest and Phantom Lady. Years later, I would learn that some of them were Frankensteined forgeries: a cover from one copy, the interior from another, staples from a third, all meticulously retouched, repaired, and reattached into a salable whole.

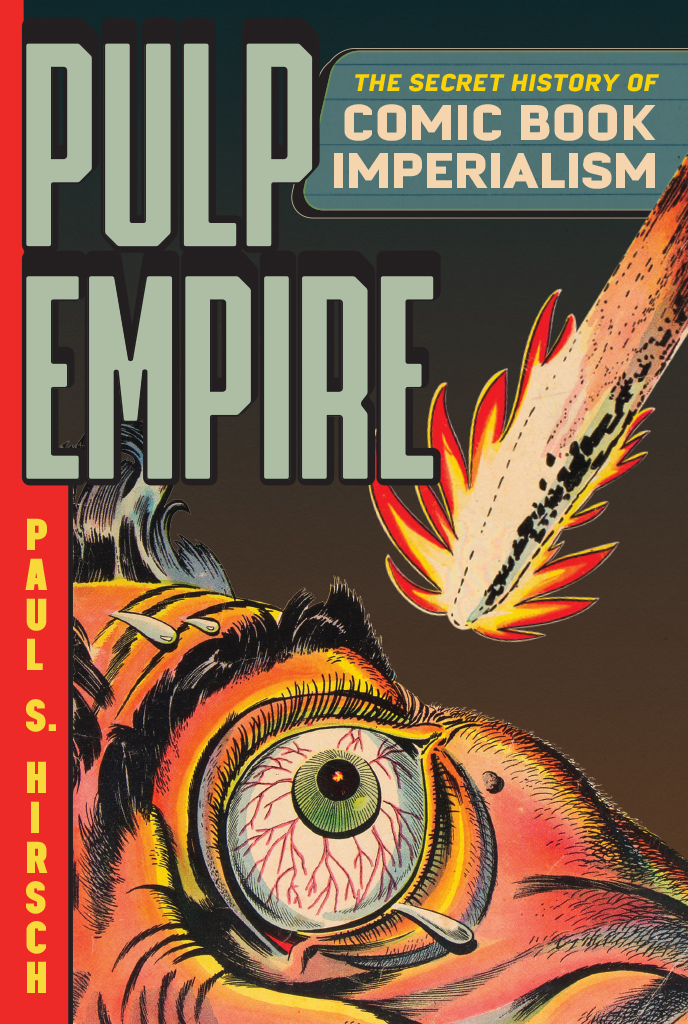

Figure I.1 This is the first issue I can remember seeing high up on the wall of my local comic book shop. The Catechetical Guild Educational Society published Blood Is the Harvest, an anticommunist propaganda title, in 1950one of many it created for distribution through religious schoolsjust six years after issuing a pamphlet called The Case against the Comics.

Next to the owner, flat on the counter, invariably lay a briefcase. Once, when I asked if he wanted help running the store, he flipped open the briefcase and pulled out a revolver. He casually pointed the gun at the ceiling tiles, tilted his head, and said, Nah, Ive already got a helper. Then, he returned the weapon to the briefcase and with an easy smile said, Tell all your friends! Of course, I didnt tell a soul; I was terrified. But some small, confused bit of my ten-year-old brain was exhilarated too. To me, comic books were primal; they were about pulp, money, funky odors, and violence both on the page and in the world.

Today, the American commercial comic book has been tamed and brought into the light. Comic book culture is beyond mainstream cultureits American culture. The New York Times reviews graphic novels, comic-themed shows proliferate on television, and one billion-dollar comic book movie after the next carries bright images of American superheroes around the world. Comic books as objects are of secondary importance, financially and culturally, to the films derived from their contents by entertainment behemoths like Disney and Warner Brothers. Yet these comic books, which initially occupied the dark periphery of the New York publishing world and were often created by poorly paid Jewish American, African American, and Asian American men and women alike, now inform the very heart of that most public, wealthy, and racially oblivious American cultural center: Hollywood. Comic book culture no longer lurks on the periphery; it lies at the very core of our shared visual vocabulary. The comic book, whether in the form of a collectible vintage title, action figure, Halloween costume, graphic novel, or film, is the epitome of American popular media at home and abroad.

It was not always so.

In the years after World War II, comics were seen as a virus: a cultural disease that spread among the young, the poor, and the dim. In America, comic books depicted the darkest, most rudimentary expressions of violence, sex, and xenophobia in the national consciousnessand these traits fueled an anticomic book campaign, anticomic book legislation, congressional hearings, and eventually a strict, self-imposed censorship code. Internationally, these same comic books showed the world that American society was racist, gruesomely violent, and soaked in sex. Wherever commercial comic books traveled at midcentury, they tarnished the image of the United States. Titles like Spectacular Adventures, Murder, Inc., and Fight against Crime depicted a shadowy culture in which criminals thrived, innocents were routinely murdered, and racism, remarkably, was even more grotesque than newspapers reported. Peppered among these stories were advertisements for bogus medicines, cheap weapons, and vibrators. Together, these contents offered global consumers a brutish image of postwar America: a modern society beset by primitive problems and a lack of concern for its young.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).