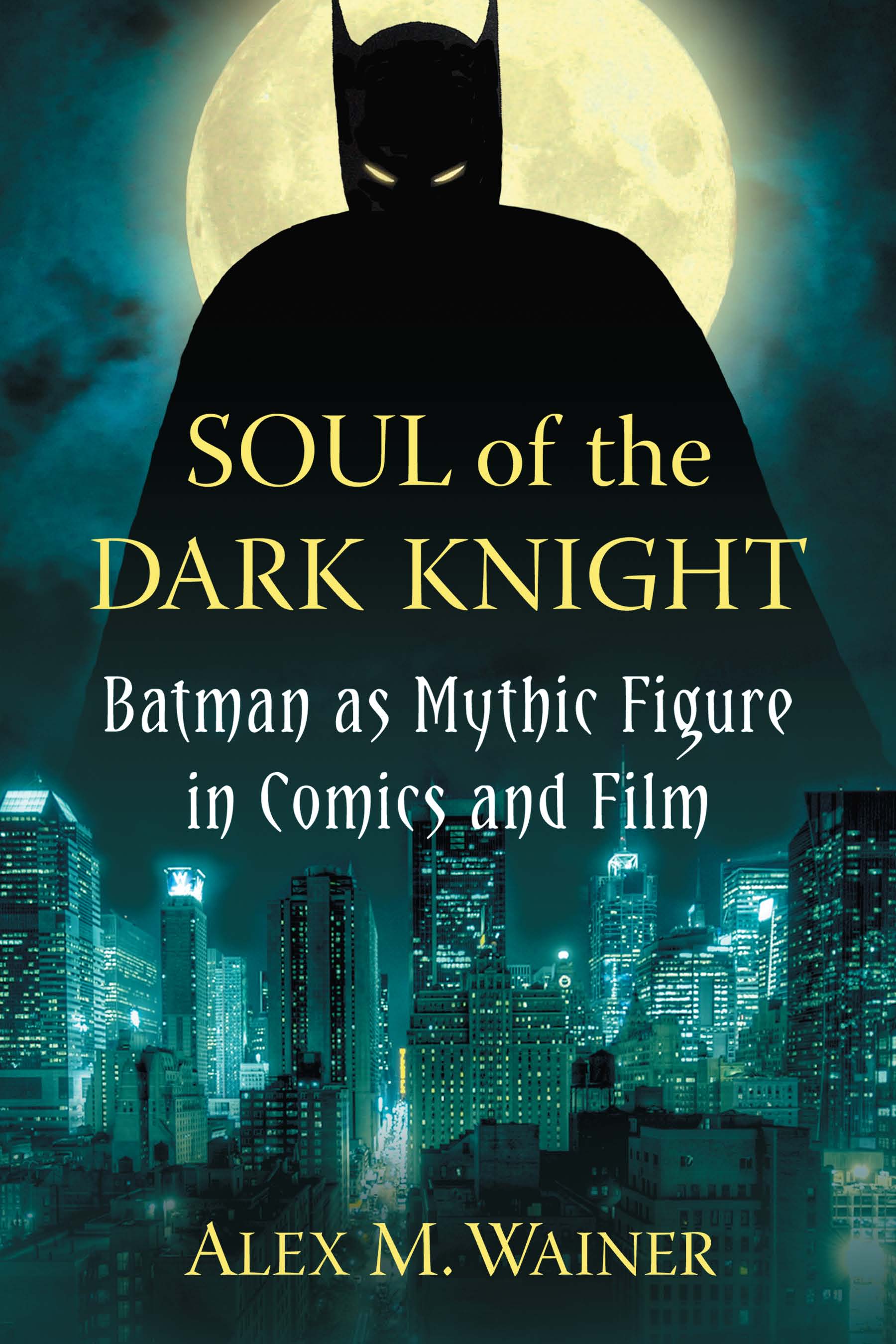

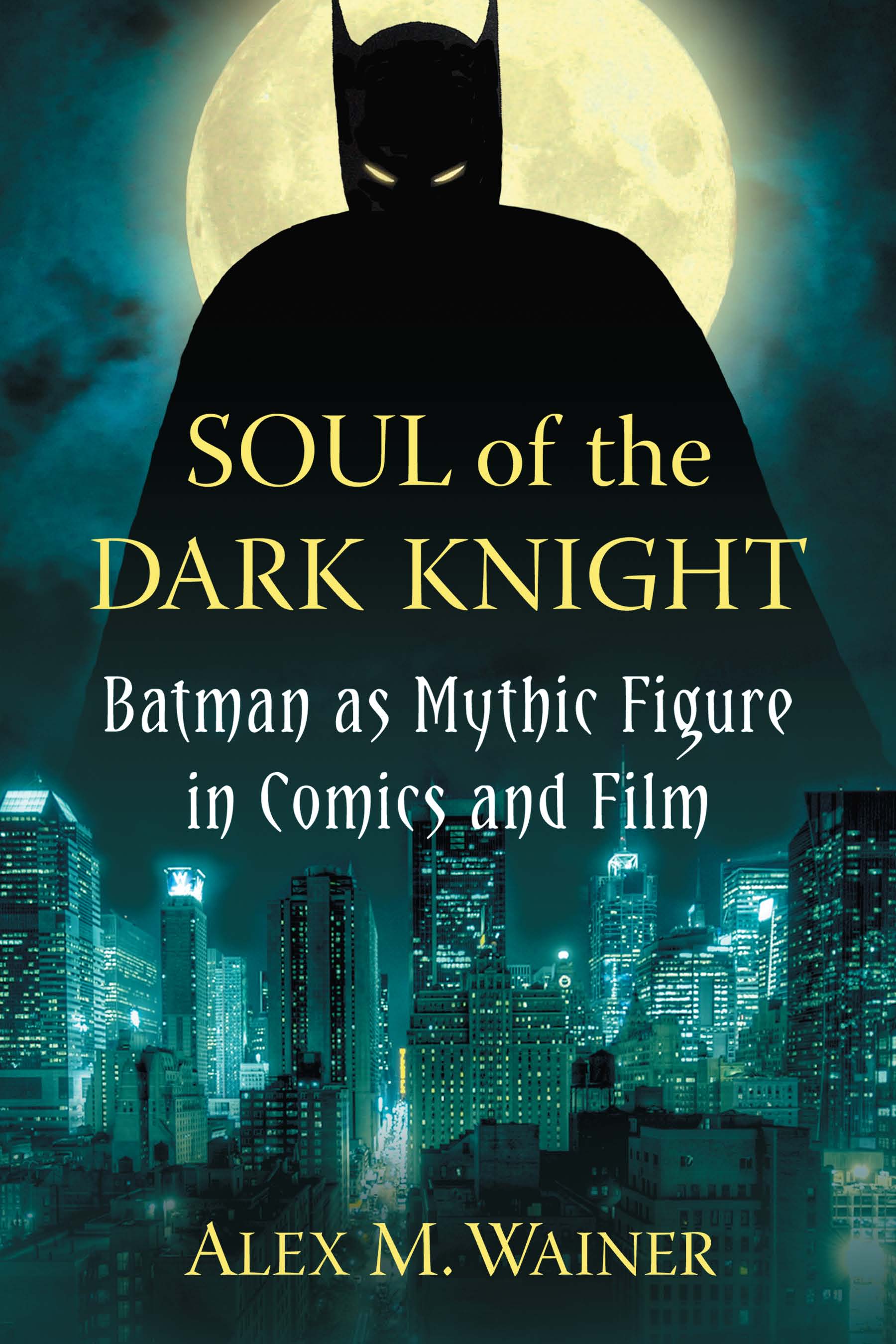

Soul of the Dark Knight

Batman as Mythic Figure in Comics and Film

Alex M. Wainer

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1505-9

2014 Alex M. Wainer. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: moon (Thinkstock); city skyline (Paulo Barcellos, Jr.)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Dedicated to Judith,

whose X-Men expertise

God used to draw us together

Acknowledgments

This work allowed me to channel the thoughts, feelings, and ideas on the subject of myth, comics and popular narratives that had been simmering in my mind since childhood. Yet it took the help of others to see these concepts developed into the form presented here. My dissertation committee chair, Dennis Bounds, came along just in time to bring his interest in comics (and his comics collection) to bear on my preliminary investigations, and his professionalism helped keep the project properly focused and executed. Committee member Michael Graves suggestions were invaluable for sharpening my scholarship. Committee member Robert Schihl had, during a class several years earlier, explained that the appeal of comics lay in their use of closure. That little seed sprouted as my research continued. Kathy Merlock Jackson gave me my first real teaching opportunity at Virginia Wesleyan College. My gratitude extends to the Regent University College of Communication and the Arts for being a place where one is encouraged to pursue the things stirring in ones mind and heart. Similarly, this manuscript preparation was made possible by Palm Beach Atlantic Universitys gracious granting of release time (and by my colleagues in the School of Communication & Media) while I was teaching classes over the past year and half.

Thomas Parhams shared interest in comics and his generosity with his collection made it possible for me to obtain a much better first-hand sense of the comics, particularly those featuring Batman. A rare friend indeed, he also went out of his way to interview four comics professionals at the 1995 San Diego Comicon: Dennis ONeil, Mark Waid, Paul Deni, and Bruce Timm. The information gleaned from these insightful interviews found its way into this text.

Pamela Robles was crucially influential in bringing this whole study to a healthy, successful fruition. From our first conversation when I barely glimpsed where I wanted to take my research, Pam, though unfamiliar with the comics medium, selflessly served as a parabolic reflector of my thinking, bouncing my thoughts back more focused than before, making me see the implications of the ideas I was working through. She also freely did yeomans work proofreading my chapters, catching a myriad of grammatical and stylistic mistakes. Muchsimas gracias, amiga.

Thanks are also due to my friend, artist Thom Marrion, who, while we were co-workers, shared his comics and gave me my first fateful look at Scott McClouds Understanding Comics. This introduction to comics theory sparked my belief in the validity of comics as an art form, making the conception of this study possible. Thanks to Randy Richards for his generous advice on preparing my manuscript. Also, thanks to Joshua Richards for his many suggestions on the crucial Introduction, and to Salvatore Ciano for helping me develop ideas in my analysis of the Christopher Nolan films. My late mother, Rachael Wainer, through her amazing generosity, made possible my educational experience from its inception to academic teaching and research.

Most importantly, my wife, Judith, worked tirelessly during the years of my research and writing, believing in me, encouraging me and just loving me as I stumbled through this work. It is not possible to imagine a better life partner.

Finally, I am grateful to God for seeing us through the valleys and the peaks of this time. I am thankful, too, for having been given a topic that is always exciting and fulfilling in so many ways.

Preface

This book on comics and Batman started with a question I was asking in the 1990s as a doctoral student in communication at Regent University. My studies stressed cinema but I was actually more taken with explaining the appeal of Batman as an enduring comic book superhero and periodic popular culture phenomenon. In 1993 I had read a new book on the nature of the comics medium, Scott McClouds Understanding Comics, and felt it explained far more about this medium than many film theories elucidating cinema. Applying McClouds theories to Batman was probably the analytical beginning of what would become a thesis that opened up into my doctoral dissertation, Mythic Expression in Comic Book Technique: Mythopoeic Aspects of Batman. I found that I needed to define what I meant by mythic, and in what way Batman could be called mythic. That opened up a world of discovery as I found authors who reflected my thinking and brought some degree of coherency to my argument. It also elevated the comics medium, particularly the superhero genre, as I began to see how well the character of Batman fit into literary analysis, particularly in the writings of Northrop Frye and C. S. Lewis. By the time I completed and defended the dissertation in 1996, I had reached the point at which I could explain why Batmans natural home was comics and how the medium was best able to express his mythic nature, and why efforts at adaptation so often fell short or felt incomplete. As a film scholar, I felt I could explain why the Batman films were flawed to varying degrees, but as a Batman fan who had seen mature treatments of the character in such graphic novels as Frank Millers The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One, I still hoped someone could succeed in adapting Batman into a great film.

When Christopher Nolans Batman Begins premiered in 2005, I was struck by how its premise aligned with the thesis of my dissertation. By foregrounding Bruce Waynes conscious strategy of constructing a mythic persona to scare criminals and offer hope to Gotham City, Nolan and his collaborators had arrived at the same conclusion as I had as to what constituted Batmans core appeal, and had done so in cinematic terms. In updating and considerably expanding my original scope, this project has become not just an analysis of Batmans mythic nature as realized by the comics medium but also a study in successful adaptation from comics to film. The chapters that follow will distinguish my intentions from other valid approaches to understanding Batman in various media. His potential for mythic narrative continually reveals new levels of meaning and entertainment.

Introduction

Seeing Through a Knight Darkly

Scene 1: 1939. Vincent Sullivan, an editor at National Periodical Publications, the publisher of Action comics, asked one of his young artists, Bob Kane, then 22, to come up with another costumed character to cash in on the popularity of Superman. In his autobiography, Kane recounts how he set to work immediately, tracing various costume designs over a generic superhero figure. Then he remembered having once seen a Leonardo da Vinci drawing of a flying machine with bat-like wings. Only 13 years old at the time, Kane had sketched figures with batwings, including one that prefigured Batman. He reworked these juvenile sketches, and soon settled on a name for his new hero: The Bat-man.

Next page