Contents

Advance Praise for

HEADSTRONG

A woman revolutionized heart surgery. A woman created the standard test given to all newborns to determine their health. A woman was responsible for some of the earliest treatments of previously terminal cancers. We shouldnt need to be reminded of their names, but we do. With a deft touch, Rachel Swaby has assembled an inspiring collection of some of the central figures in twentieth-century science. Headstrong is an eye-opening, much-needed exploration of the names history would do well to remember, and Swaby is a masterful guide through their stories.

Maria Konnikova, New Yorker writer and New York Times bestselling author of Mastermind

Headstrong is a true gem. So many amazing women have had an incredible impact on STEM fields, and this book gives clear, concise, easy-to-digest histories of fifty-two of themtheres no longer an excuse for not being familiar with our math and science heroines. Thank you, Rachel!

Danica McKellar, actress and New York Times bestselling author of Math Doesnt Suck

Rachel Swabys fine, smart look at women in science is a much-needed corrective to the recorda deftly balanced field guide to the overlooked (Hilde Mangold), the marginalized (Rosalind Franklin), the unexpected (Hedy Lamarr), the pioneering (Ada Lovelace), and the still-controversial (Rachel Carson). Swaby reminds us that science, like the rest of life, is a team sport played by both genders.

William Souder, author of On a Farther Shore and Under a Wild Sky

Copyright 2015 by Rachel Swaby

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Broadway Books and its logo, B \ D \ W \ Y, are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Permission acknowledgments can be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Swaby, Rachel.

Headstrong : 52 women who changed scienceand the world / Rachel Swaby.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Women scientistsBiography. 2. Women astronomersBiography. 3. Women physiciansBiography. 4. Women biologistsBiography. 5. Women physicistsBiography. 6. Women mathematiciansBiography.

I. Title.

Q130.S93 2015

509.252dc23 2014041421

ISBN9780553446791

eBook ISBN9780553446807

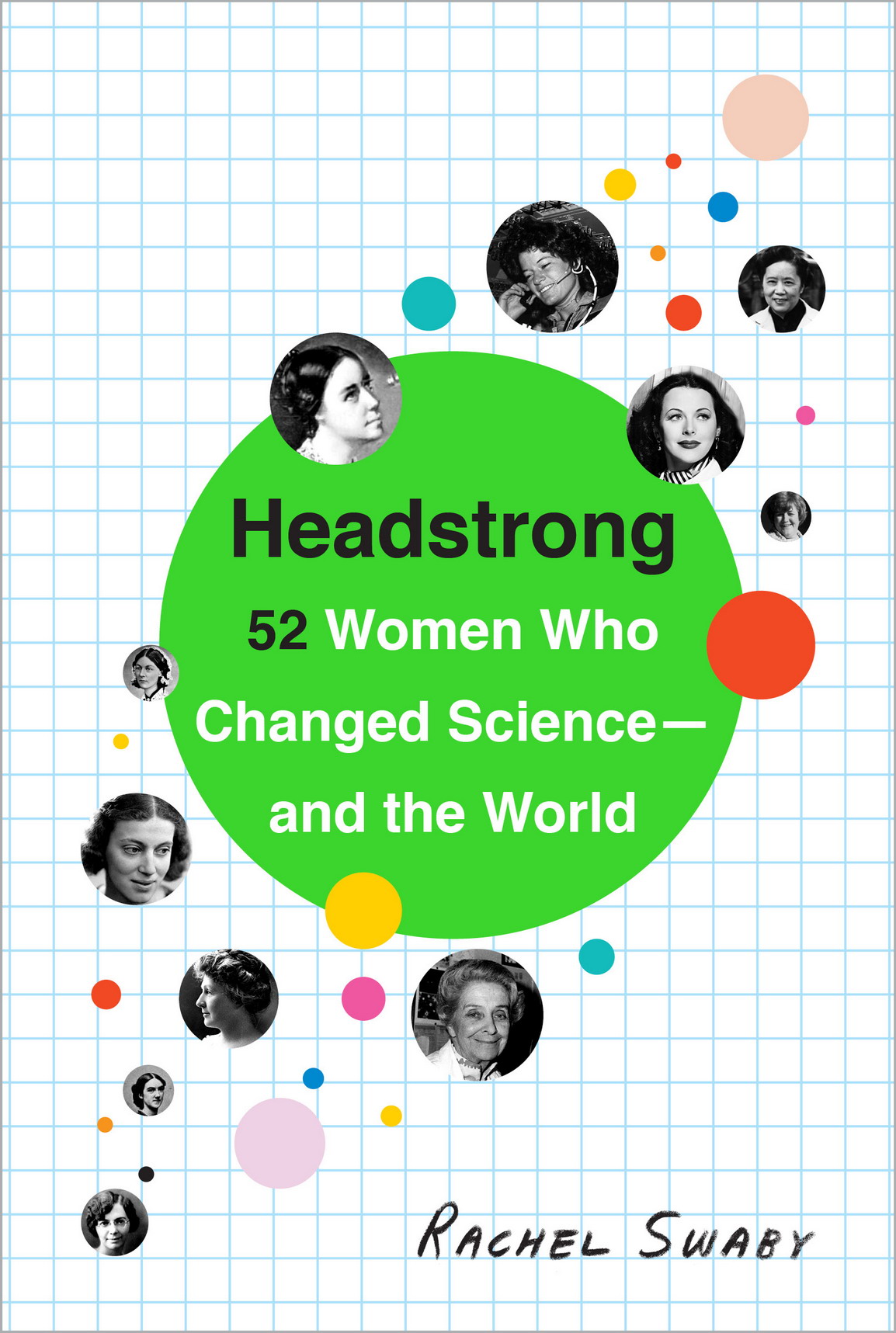

Cover design by Na Kim

Cover photographs: Clockwise from top left: (Sally Ride) U.S. National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain; (Chien-Shiung Wu) Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image SIA2010-1507; (Hedy Lamaar) Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain; (Yvonne Brill) Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University; (Rita Levi-Montalcini) Mondadori Portfolio; (Alice Ball) Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain; (Ellen Richards) Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain; (Annie Cannon) Library of Congress [Reproduction number LC-USZ62-115881]; (Dorothy Hodgkin) Peter Lofts Photography/National Portrait Gallery, London; (Florence Nightingale) Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division [Reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsca-037769]; (Maria Mitchell) Sweeper in the Sky: The Life of Maria Mitchell, First Woman Astronomer in America by Helen Wright, 19141997. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1949. Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

v4.1

a

For Tim

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This book about scientists began with Beef Stroganoff. According to the New York Times, Yvonne Brill made a mean one. In an obituary published in March 2013, Brill was honored with the title of worlds best mom because she followed her husband from job to job and took eight years off from work to raise three children. Only after a loud, public outcry did the Times amend the article so it would begin with the contribution that earned Brill a featured spot in the paper of record in the first place: She was a brilliant rocket scientist. Oh right. That.

The errorstroganoff before science; domesticity before personal achievementis so cringe-worthy because its a common one. In 1964, when Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin won the greatest award that chemistry has to offer, a newspaper declared Nobel Prize for British Wife, as if she had stumbled upon the complex structures of biochemical substances while matching her husbands socks. We simply dont speak of men in science this way. Their marital status isnt considered necessary context in a biochemical breakthrough. Employment as an important aerospace engineer is not the big surprise hiding behind a warm plate of noodles. For men, scientific accomplishments are accepted as something naturally within their grasp.

In 1899, the inventor and physicist Hertha Ayrton put on a demonstration showing her latest breakthrough in calming the temperament of the arc light, long notorious for hissing and flickering. When the newspaper reported on the presentation, it treated Ayrton like some kind of circus performer: What astonished the lady visitorswas to find one of their own sex in charge of the most dangerous-looking of all the exhibits. Mrs. Ayrton was not a bit afraid. Annoyed by this and many other similar perspectives, Ayrton called out a persistent problem with the way she and her contemporaries like Marie Curie were treated: The idea of women and science is entirely irrelevant. Either a woman is a good scientist or she is not; in any case she should be given opportunities, and her work should be studied from the scientific, not the sex, point of view.

Even today, its important we hear those words again. We need not only fairer coverage of women in science, but more of it.

Access to role models really matters for girls coming up in the STEM fields. Sally Ride turned her father into an advocate for the cause. After coming across an advertisement featuring a boy daydreaming about the day he would go up into space, Rides father wrote a strongly worded letter to the advertiser pointing out an inherent bias in educating children that should be corrected. As a parent of the first US woman astronaut, I know first hand that girls also aspire to math and science and we should encourage her to get Americas future off the ground. In a New York Times Magazine article, Eileen Pollack, one of the first two women to earn a bachelors degree in physics at Yale, noted the large poster of famous mathematicians hanging in her alma maters math department lobby, whicheven at the time of the article, in 2013didnt include a single woman. She had opted not to continue on in science. In early 2014, a seven-year-old named Charlotte wrote an open letter to Lego. I went to a store and saw Legos in two sections, the pink [girls] and the blue [boys]. All the girls did was sit at home, go to the beach, and shop and they had no jobs but the boys went on adventures, worked, saved people, and had jobs, even swam with sharks. I want you to make more Lego girl people and let them go on adventures and have fun ok!?!

As girls in science look around for role models, they shouldnt have to dig around to find them. By treating women in science like scientists instead of anomalies or wives who moonlight in the lab as well as correcting the cues given to girls at a young age about what theyre good at and what theyre supposed to like, we can accelerate the growth of a new generation of chemists, archeologists, and cardiologists while also revealing a hidden history of the world.