A LSO B Y T IMOTHY J. G ILFOYLE

City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution,

and the Commercialization of Sex, 17901920

Millennium Park: Creating a Chicago Landmark

TO THE WOMEN OF MY LIFE

Mary Rose Alexander

Maria Gilfoyle

Danielle Gilfoyle

Adele Alexander

and

IN MEMORIAM

Mary Dorothy Norton Gilfoyle

Contents

List of Illustrations

A gambling saloon in gold-rush California, filled with Euro-Americans,

Chinese, and Mexicans.

This 1856 advertisement for Quimbo Appos New Haven tea business

reflected his economic success.

The Hudson River Railroad line running through the Sing Sing grounds

generated numerous escape attempts by inmates.

As late as 1908 the penitentiary and charity hospital

on Blackwells Island still did not have a wall.

Maguires Hop Joint was behind Niblos Garden Theater on

Crosby Street in 1870.

The main cellblock of Sing Sing with the workshops and Hudson River

in the background.

George Appo shot in Poughkeepsie, as depicted in

the National Police Gazette .

Michael Riordans attack on George Appo made the headlines of

the New York Tribune .

With his performance in In the Tenderloin , Appos name was plastered

on billboards all over the city.

George Appos gravestone in Mount Hope Cemetery in

Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

Preface

I N 1840 N EW Y ORK C ITY had no professional police force, a low murder rate, and no bank robberies. Within decades, however, this changed; serious crime proliferated and modern law enforcement was born. By 1890 Gothams police budget had grown more than sixteenfold and became New York Citys single largest annual expenditure. Detective work was transformed into a public and private specialty. The murder rate had doubled, and larceny comprised one-half to one-third of all prosecuted crime in the state. Newspapers regularly reported that illegal activities were rampant, the courts and police powerless. New York City had become the evillest [sic] spot in America. For the first time, observers complained about organized crime.

A new criminal world was born in this period. It was a hidden universe with informal but complex networks of pickpockets, fences, opium addicts, and confidence men who organized their daily lives around shared illegal behaviors. Such activities, one judge observed, embodied an innovative lawlessness based on extravagance, greed, and the pursuit of great riches. A new class of criminals now existed. Many of these illicit enterprises were national in scope, facilitated by new technologies like the railroad and the telegraph, economic innovations like uniform paper money, and new havens for intoxication like dives and opium dens. For the first time both criminals and police referred to certain lawbreakers as professionals.

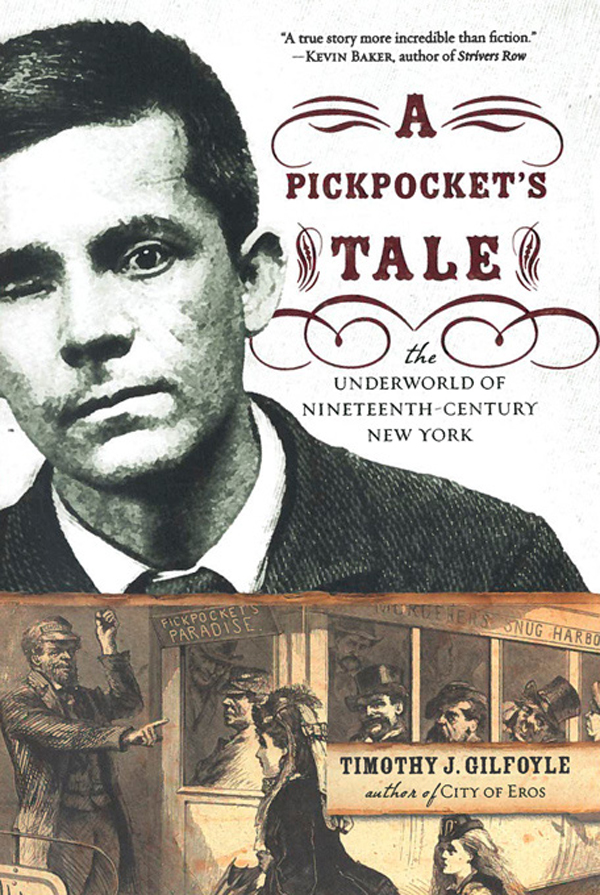

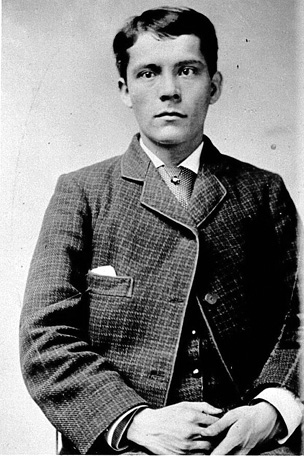

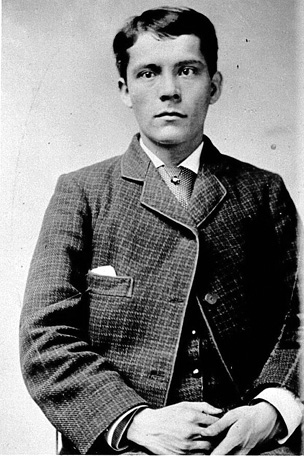

George Appo was one such professional criminal. At first glance Appo hardly seemed a candidate for any criminal activity; his diminutive size and physical appearance evoked little fear. By age eighteen he stood less than five feet five inches in height and weighed a slight 120 pounds. Everything about him seemed small: his narrow forehead, short nose, compact chin, and tiny ears that sat low on his head. Although Appos face displayed features of his mothers Irish ancestry, his copper-colored skin reminded some of his fathers Chinese origins. Appos brown eyes were less noticeable than his pitch-black hair and eyebrows, the latter meeting over his nose. The tattoos E.D. and J.M. were inscribed on his left and right forearms, respectively.

George Appos rogues gallery photograph.

But Appo was one of New Yorks most significant nineteenth-century criminals. A pickpocket, confidence man, and opium addict, he lived off his criminal activities during his teenage years and much of his adult life. On successful nights during the 1870s and 1880s, he earned in excess of six hundred dollars pilfering the pockets of those around him, equivalent to the annual s alary of a skilled manual laborer. Even more lucrative was the elaborate confidence scheme known as the green goods game. The most successful operatorsgilt-edged swindlers according to oneaccumulated fortunes in excess of one hundred thousand dollars. By 1884 Americas most famous detective, Allan Pinkerton, identified the green goods game as the most remunerative of all the swindles, the boss racket of the whole confidence business.

Appo made money, but his life was hardly a Horatio Alger tale of self-taught frugality and upward mobility. The offspring of a racially mixed, immigrant marriage, Appo was separated from his parents as a small child. Effectively orphaned, the young boy grew up in the impoverished Five Points and Chinatown neighborhoods of New York. He never attended school a day in his life. Appo literally raised himself on Gothams streets, becoming a newsboy and eventually a pickpocket and opium addict. This new child culture of newsboys, bootblacks, and pickpockets, fed by foreign immigration and native-born rural migration, mocked the ascendant Victorian morality of the era. New York needed no Charles Dickens to create Oliver Twist or Victor Hugo to invent Jean Valjean. Gotham had George Appo.

Appos youthful adventures persisted into adulthood. For more than three decades he survived by exploiting his criminal skills. Appo patronized the first opium dens in New York, participated in the first medical research on opium smoking, and appeared in one of Americas first theatrical productions popularizing crime. On at least ten occasions he was tried by judge or jury. As a result he spent more than a decade in prisons and jails. Therein he experienced New Yorks first experiment in juvenile reform with the school ship Mercury , as well as the lockstep, dark cells, and industrial discipline of American penitentiaries. He personally witnessed the lunacy found in the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, the easy escapes from the Blackwells Island Penitentiary, and the corruption associated with the nations largest jail: New Yorks Tombs. During various incarcerations Appos teeth were knocked out, and he encountered a wide array of prison tortures. Life outside prison was even bloodier. On the street Appo was physically assaulted at least nine times, shot twice, and stabbed in the throat once. More than a dozen scars decorated his body.

Above all George Appo was a good fellow, a character type he identified and wrote about. A good fellow engaged in criminal activities while displaying courage and bravery, a nervy crook, in Appos words. Good fellows like Appo did not rely on strong-arm tactics to get their way. Instead they avoided violence, employing wit and wile to make a living. Theirs was a world of artifice and deception. When successful, a good fellow lavished his profits on others. He was a money getter and spender. Such mettle, pluck, and camaraderie implied a level of trustworthiness, mutuality, and dependability. Above all a good fellow was loyal, willing to withstand, in Appos words, the consequences and punishment of an arrest for some other fellows evil doings both inside and outside of prison.

The lives of individuals like Appopickpockets, street children, confidence men, opium addicts, counterfeiters, convictsremain hidden. While historians have explored organized crime and wise guys in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, nineteenth-century men like Appo are enigmas. Theirs was largely an invisible world, dependent on camouflage and duplicity, organized around an oral culture. Inconsistent arrest records, exaggerated eyewitness accounts, and little participant testimony present difficult interpretive problems in discerning the realities much less the complexitiesof unlawful behavior. The social environments and networks of criminals, specifically the actual workings of the underground or informal economy, are uncharted territory. Criminal life in nineteenth-century America remains a mystery.

Next page