For Emily, Elizabeth and Nicholas

In the spring of 2007 in a crowded Beijing restaurant an elderly Chinese man rose to his feet and silenced his fellow diners with a song he had learnt as a child:

Three blind mice, three blind mice,

See how they run, see how they run

They all ran after the farmers wife

She cut off their tails with a carving knife

Three blind mice, three blind mice.

Although seventy-five years old, Nieh Guanghan had a strong tenor voice, and to the bafflement of the restaurant he reeled off a number of other English nursery rhymes, finishing with a rousing rendition of:

Londons Burning,

Londons Burning,

Fire! Fire!

The elderly Chinese guests had all learnt those and other songs by heart as children. They had gathered to share their memories of the man who had taught them to sing English nursery rhymes, and to whom they owed their lives, a young Englishman who became both their headmaster and their adoptive father at the height of the SinoJapanese war in the 1940s.

His name was George Aylwin Hogg, and in a few brief years during the three-sided war in China he achieved legendary status in the north-west of the country. Although unknown in his own homeland he remains well loved and remembered by those he met and cared for in the brief years he worked in China before his death in July 1945.

It was in China in 1984 that I had first come across the story of Hogg, when I was working for the London Daily Telegraph as holiday relief in the Beijing bureau. After several barren days searching for a decent story I went to the British Embassy Club for a quiet beer. There I overheard a British diplomat complain that he had to fly to the town of Shandan in the remote north-west of the country, because the Chinese authorities had erected the bust of an Englishman in the town.

Strange things were happening in Beijing at the time. Mao Tse-tung had died in 1976, allowing Deng Xiaoping to return from disgrace and begin the economic liberalisation that was to set China on the path to todays burgeoning market economy. The first McDonalds had opened in Beijing. Cars were just beginning to challenge the many millions of bicycles on the streets of the capital. Western businessmen were arriving with every flight at the international airport. Nevertheless, the idea that China would honour an unknown Englishman with a bust seemed preposterous.

But it turned out to be true. In August that year some eighty elderly gentlemen gathered in Shandan to join local officials and a number of VIPs from Beijing to mark the reopening of a school and library. There were eloquent speeches to mark the reconstruction of a tomb and gravestone desecrated by Red Guards during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Flowers and wreaths were laid on the grave. A statue was unveiled. Old men shed tears.

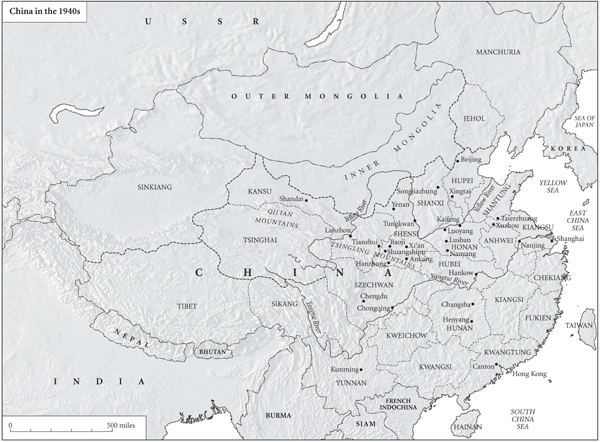

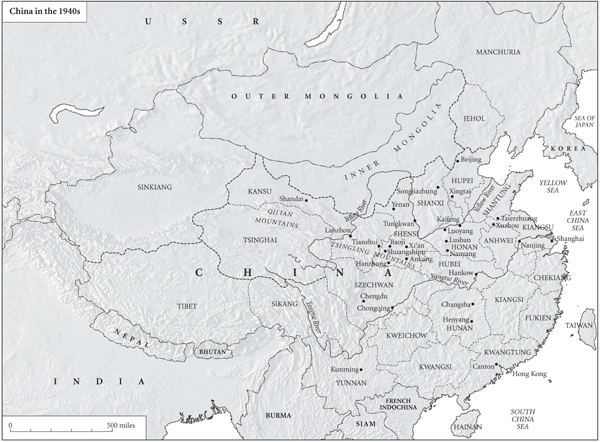

The man whose memory was being was honoured had ended an epic journey and his life in this remote region of China in 1945. George Hoggs work in the Chinese co-operative movement in the 1940s, and later as headmaster of a school for war orphans, would always have earned him the tribute of later generations. But what made him a hero to the Chinese was the ten-week journey he made in 1945, against all odds, over the highest mountains in western China with a school of young boys in the worst winter for twenty years, seeking and finding sanctuary from the Japanese on the edge of the Gobi desert. The elderly men who had travelled to Shandan in the summer of 1984 were all Hoggs old boys who survived that terrible journey nearly forty years earlier.

Sadly, I did not have time to take the two internal flights and make the then sixteen-hour car journey to join them at the graveside ceremony. The Telegraph had cut short my stint in China with a characteristically curt instruction to go to Hong Kong. I only had time to file a news story about the honour paid to an unknown Englishman before heading for Beijing airport.

Back in London, I took a closer look at George Hogg, and discovered that he had been a great deal more than the heroic headmaster of a school in wartime China. In a book, in his letters and through his journalism he had left behind a record of China at war with itself as well as with Japan in the years 193845. He reported the conflict through the eyes of the people who bore the brunt of its savagery: the peasant farmers, the school teachers, the women and children everywhere in the countryside.

No one sent George Hogg to China. It was pure luck that brought him to Shanghai at such an extraordinary time. He rode his luck for eight years, surviving a medical dictionary of serious diseases, countless brushes with death and terrifying journeys over the mountains of western China on every conceivable type of transport. Young, confident and courageous, he ignored the risks he was running. But he did once confide that sliding and skidding over icy mountain roads in ancient trucks was a good deal more frightening than slipping through the Japanese lines at night.

His journalism and regular letters home are a record of a young man struggling to come to terms with the brutality of a war in which some fifteen million people lost their lives between 1937 and 1945. He witnessed repeated atrocities inflicted upon defenceless civilians. The massacres in Nanjing in 193738, when as many as 260,000 people died at the hands of the Japanese, were not isolated war crimes. They were an extreme example of routine tactical terror to break popular resistance to the Japanese plan to turn China into a servile client state.

Occasionally usually when spattered with mud and blood in some bombed-out village Hogg yearned for the dreamy world of Oxford and the comforts of the middle-class life in the home counties that he had left behind. But he never lost his enthusiasm for his work in China. In his heart he knew he would never return home.

While working as a news agency stringer Hogg found time to write a book, I See a New China. It was favourably reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic, although one reviewer criticised the authors adolescent tone in writing about the twists and turns and endless atrocities of the SinoJapanese war.

But that was the whole point of George Hogg. He bounded out of Oxford with all the enthusiasm and navet that three years in a great university confers upon a self-confident young man of twenty-two. He had been brought up from childhood to think the best of people, and to do his best for them. Throughout the eight years he spent in China his letters are coloured by cheerful exuberance, a belief in the essential benevolence of humanity and a refusal to be downcast by evidence to the contrary.

He travelled light as he crisscrossed north-west China, moving from one war zone to another; but whether on foot, on horseback or on top of an ancient truck, he always found room for his typewriter. Hogg never stopped writing: letters, short stories, news stories and features. His reporting of the developing industrial co-operative movement in China, which had been initiated in 1938 to replace the countrys shattered manufacturing base, led to a job offer that was to change his life. He joined the movement as a publicity director, with the title Ocean Secretary, in 1941. The title reflected the general use of the term ocean in Mandarin to denote anything foreign foreigners throughout Chinese history have been known as ocean devils. This led him in 1942 to become headmaster of a co-operative training school in the remote mountain town of Shuangshipu. It was here, at the crossroads of the Tsingling mountains in north central Shanxi province, that George Hogg found his destiny.