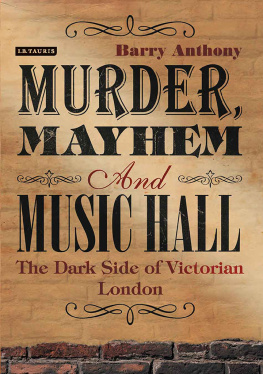

In loving memory of Tom, Gwen and Kitty, and of my brother Terry, whose ambition in life was to see this book written

Who is to write the history of music hall? What a splendid theme

JOHN ROBERTSON, HISTORIAN (18561933)

In March 1962, I sat with an old man as he lay dying. He was barely conscious, with familiar half-smiles dancing across his well-worn and gentle face, but I knew where he was in his imagination where he wanted to be. The lights were bright. A boisterous audience was cheering. Aged eighty-two, and over thirty years since he had left it, he was back on the stage. In life he had few possessions, but he died a richer man than most, with a song in his heart and joy in his soul.

He was my father, Tom.

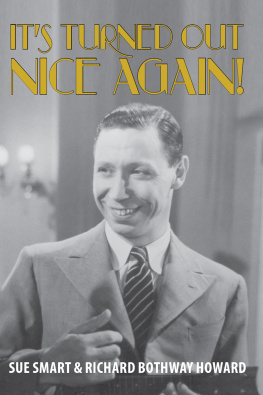

The men and women who entertained so royally are all dead. They are gone, but not quite forgotten. We know some of their names, and some of their songs, but few people now living saw them onstage. Their magic is now the stuff of myth and legend.

But then, music hall has always been an elusive concept. What exactly is it? Is it a style of singing comic ballads? That is certainly the principal ingredient, but it is far from the whole. Is it a theatre, hosting a mixture of variety? Up to a point, yes but it is so much more than that.

Even the name is misleading. Music hall was never simply music, but encompassed everything from the sublime to the surreal. A typical evenings fare might include opera and ballet, popular singers and comedians, speciality acts, animal acts, acrobats, monologists and any other performer who might, however loosely, entertain. Nor was the setting necessarily a hall. Elements of music hall were widespread in pleasure gardens, taverns, streets and markets long before the nineteenth century. Its growth was organic: often haphazard, ramshackle more the product of events than rational planning. And always, always it was a reflection of the lives and tastes of its audience.

The term music hall was invented by the early entrepreneurs who built theatres to exploit widely popular forms of entertainment. These entrepreneurs have a role to play in the history of music hall, but it is sentimental myth to claim they invented it. It had its heart in the East End of London, yet it was not purely a southern phenomenon. It was centred on the capital because that was where the biggest audiences were to be found, but from the outset it was popular in towns and cities across the length and breadth of Great Britain. Lancashire, in particular, provided music hall talent almost on a level to rival London.

Music hall was able to thrive because of a fortunate combination of circumstances. In Victorian Britain, wages rose and working hours fell. The nineteenth century was an intensely musical era that saw a huge growth in choral societies, brass bands and religious music. Street entertainers earned a few pennies playing zithers, piccolos, banjos, concertinas or fiddles. Opera companies toured the provinces. Popular music embraced minstrel songs and the ballads of Tin Pan Alley. Popular operetta arrived as the gift of Gilbert and Sullivan. The development of railways enabled performers to tour the whole country. Demand for their work saw the publication of inexpensive sheet music. There was a huge growth in the sale of musical instruments. Amidst all this, music hall was shaped and defined as one of the glories of the Victorian era. Sentimental, vulgar, class-conscious, insular but always patriotic, and on the side of the underdog. It held up a mirror to peoples hopes and fears, joys and heartbreaks, and the general absurdity of life.

The strands of music hall began to come together in the early nineteenth century, but had comprehensively disentangled by the mid-twentieth. Like a shooting star, it flared brightly into orbit, then fizzled out; but its heyday was brilliant, and its lifespan encompassed the story of a world changed beyond recognition.

In its formative years, the vulgarity and sentimentality of music hall attracted a largely working-class audience, but its appeal was far wider. It took root in England only a few years after there had been a real fear of revolution, and helped to turn sour resentment into a patriotic roar of joy. It was low-born but irresistible. Its songs have become the folk songs of a nation. As Kipling observed, they filled a gap in our history. Music hall attracted the magic brush-strokes of Sickert, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec. Long after its heyday, entertainers such as Max Miller, Tommy Cooper, Frankie Howerd and Morecambe and Wise had an empathy with their audience reminiscent of music hall in its prime. Bruce Forsyth and Roy Hudd have it to this day.

Popular artistes from music hall shaped the attitudes of our nation: Harry Lauders nightly jokes about Scottish miserliness fed a public perception that turned a myth into an accepted truth. Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel and Dan Leno personified the little man, put upon by life. Other stereotypes entered folklore. Music hall eulogised courtship and motherhood, yet ridiculed marriage as a comic disaster. It mocked single women for being unmarried, but made the missus the butt of jokes. It was never politically correct, and in a less sensitive age nigger minstrels and coon acts were part of its staple diet. At times of war it could be fiercely jingoistic indeed, the word was popularised in By Jingo, a music hall song, during the Baltic crisis of 187778. Even after its demise, music hall continued to have an impact. In 1942, the pro-nudist magazine Health & Efficiency denounced music hall comedians and their imbecilic jokes for the reluctance of the public to join nudist camps. More positively, the demand for entertainment without alcohol led to the foundation in 1880 of the Old Vic theatre in south London.

Once scorned, music hall would come to be seen as epitomising a past age of success, and as an art form that gave pleasure to millions. It had some powerful advocates. In 1978, James Callaghan, then Prime Minister, used a music hall song at a TUC congress to announce that he would not be holding an expected general election: There was I, waiting at the church he sang, echoing Vesta Victoria three-quarters of a century earlier. The country was praying for an election but it was not to be. Nor was this an isolated acknowledgement of Callaghans affection for music hall. At another trades union gathering he charmed his dinner companions by singing, Im the man, the very fat man, who waters the workers beer. It is an irony that he used a music hall song to draw grumpy trades unionists closer to the government, since over seventy years earlier disputes over music hall had bitterly divided the Puritan and non-Puritan elements of the embryonic Labour movement.

Tories were susceptible too. Lord Randolph Churchill had an almost music hall style of public speaking, claimed his biographer, while his son Winston, a great admirer of the music hall artiste Dan Leno, was apt to sing old world cockney songs with teddy bear gestures. Churchill, like the Labour movement, will enter our story again.

Music hall reached its zenith in the 1890s. Vast auditoriums were packed each night in nearly every British town and city, and fourteen million tickets were sold each year. The most popular performers were among the highest-paid and most celebrated figures in the land. I earn more than the Prime Minister, noted Little Tich, but I do so much less harm. Owners of theatres became rich, and their money and fame gave them an entre to the Establishment elite. But even as music hall stood unchallenged in its supremacy, the forces that would destroy it were taking shape.