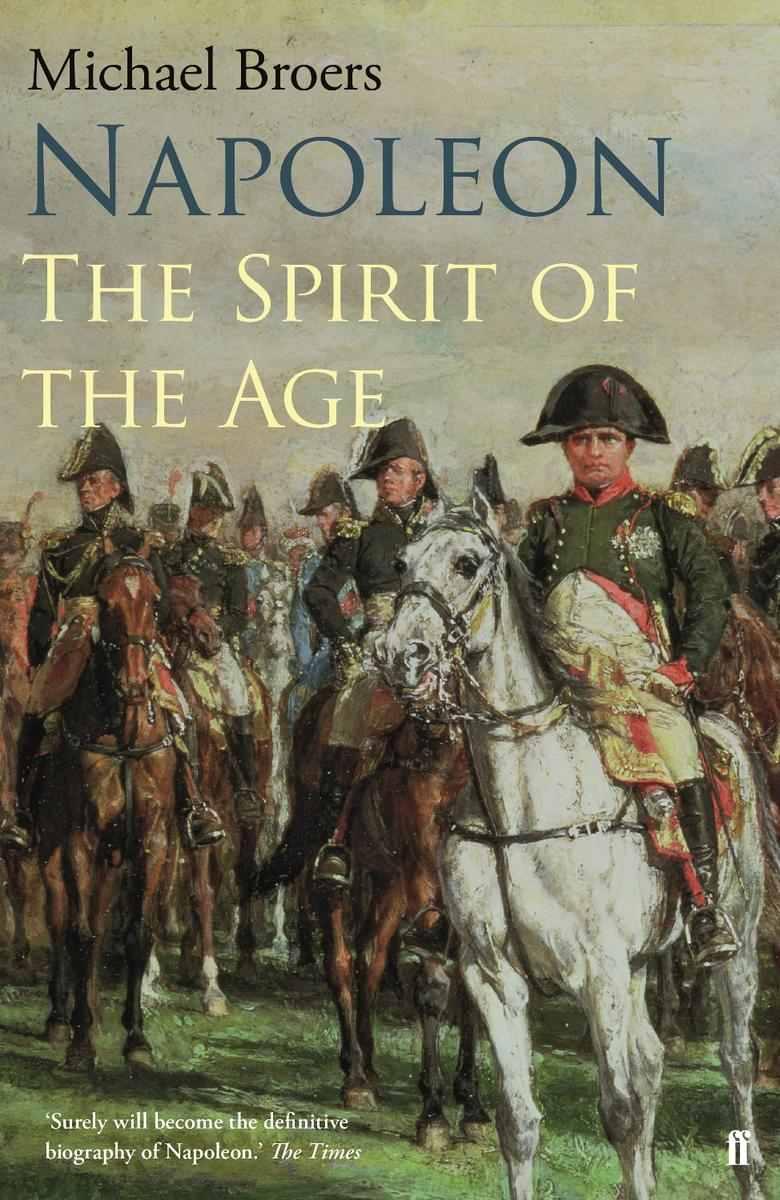

NAPOLEON VOLUME 2 The Spirit of the Age, 18051810

MICHAEL BROERS

For Bill Speck,

A fine scholar and a finer friend

Et Philippe Bchu,

Mon frre du lait,

nos projets

Now both sadly lost to us CONTENTS

Like a wolf upon the fold A line had been drawn in the last months of 1805, when war began anew on the European continent. The onset of the war of the Third Coalition, when Britain had at last persuaded Russia and the Habsburgs to take the field against France, left a far more indelible mark on Napoleons regime, his empire and his own life than his coronation as Emperor of the French less than a year earlier. Caught off guard, which the protestations of his own myth-making hid so well for so long, Napoleon saw his hand forced by British diplomacy and Austrian belligerence. He now had to risk the hard-won political, social and financial stability his reforms had given to France. Even before a shot had been fired, the costs of war threatened economic recovery and financial rectitude; the re-imposition of conscription on so vast a scale saw the resurgence of rural disorder that showed signs of developing into counter-revolution. Defeat in the field would mean the end of everything personal and political. Until now, Napoleon had presented himself as the new Augustus at Notre Dame on 4 December 1804, as he placed the laurel wreathed crown on his own head. Everything he had done in power, from the conclusion of the second Italian campaign until the outbreak of war, had sought to make safe the world of the prosperous, civilised, gentle masses of granite, for even the catastrophic expedition to reclaim Saint Domingue had been driven by the commercial interests of the merchants of the Atlantic ports and their Parisian bankers; the war with Britain had been portrayed as a struggle to reclaim the sea lanes and the overseas empire for French trade. His political project hinged on ralliement and amalgame , policies of reconciliation, co-operation and live and let live between the factions of the revolutionary decade. The ethos of the Consulate and the first year of the Empire had been, at heart, the lesson Napoleon said he owed to his lawyer father: that men Frenchmen, at least should be reconciled, not estranged from each other.The war of 1805 ended this. Before it began, Napoleons life had been akin to the wanderings of Odysseus: He had had to outwit monsters and rivals; like Beaumarchais Figaro, his most effective weapon had been his intelligence. Henceforth, his journey and that of his empire and its people, became a different kind of epic, a decade of bitter conflict, the same length as Homers Trojan War. It contained all the stuff of heroic legend: death, gore and suffering on a scale hitherto unknown and unrivalled even in the annals of the Antiquity in which Napoleon and his generation were steeped. It would engender triumph and humiliation of an intensity rivalled only in Greek tragedy, just as its sweep encompassed the length and breadth of a continent. Indeed, it would prove an epic more Wagnerian than Homeric, a struggle to the death with the rest of the world, which would engulf and destroy even Napoleon himself. The intensity of the ten years struggle that began in late 1805 turned friend and foe alike into physical wrecks before their time, having begun their wars as young tyros, only to end them as empty husks. Castlereagh, the foreign minister who did so much to galvanise the British war effort, was born in the same year as Napoleon, 1769, and died the year after his arch-enemy, in 1822; he cut his own throat, but even so censorious an age as his recognised that this intense workaholic had become mentally ill. Napoleons right hand, his stepson Eugne de Beauharnais, died from sheer exhaustion in 1824, at only forty-three. Part of the epic of this blood-drenched decade is Napoleons own physical and, at moments, mental degeneration. From the front ranks of the ghastly butchers yards called battles, to the corridors of power, youth destroyed itself in a prolonged struggle for supremacy. It was not a time of half measures.In the years covered in this volume, the players in the great game that opened in the last weeks of 1805 were either exposed as inadequate by Napoleon or began to rise to the challenge he posed them. It took time, however, and few did so until he had beaten them in the field and at the conference table at least once, so ferocious and original was his assault on their world. The first years saw Napoleon conquer Europe, sweeping aside or fighting to a bloody draw every major land power on the continent. They saw his empire reach its zenith, and his hegemony its apogee. What began in late 1805 as a desperate gamble to save himself ended in the humiliation of the Habsburgs, on the battlefield at Wagram in 1809, and in the bedroom, when he forced them to agree to his marriage to the daughter of Emperor Francis in 1810. It saw his siblings put on thrones, though it ended with one of them deposed and the others reduced to vassals. It saw his armies evolve from the force that marched out of the Channel camps into a truly multi-national European army, one almost invincible. It truly did turn Napoleon into the Alexander the Great of his times, for Napoleons reputation as the great warrior had hitherto been largely of his own making. The great French public or, at least, some urban literati may have believed his self-publicity, although a clutch of royalist journals refused to concur, even within the Parisian bubble. Seen in the cold light of day, however, his military record led few of his peers, friend or foe, to dread him. All this changed in a few bleak winter weeks. No one foresaw it in the wet, cold early winter of 1805.Fittingly, when it began, the Napoleonic epic did so in a flash, as the armies of the great, old dynastic empires moved on the fledging rouge state, the Empire of the French. Suddenly, Napoleon had to take a new course. Not only had he to turn around physically and strategically in the last weeks of 1805, but psychologically. His mental agility had been tested again, but this time for higher stakes and on a grander scale than ever before. The world would soon learn that, like Giovanni Battista Fidanza, the Ligurian central character of Joseph Conrads Nostromo , that man could command himself even when thrown off his balance this fitted Napoleon as well as Conrads charismatic hero. Napoleon pivoted, kept his balance, and headed south to meet the enemy at all speed, and in good order.Above all, this is the story of a general and his army, of their rampage across the old continent of Europe. If the young emperor of the west struck ruthlessly and swiftly, it was because of his new masterpiece, now rechristened la Grande Arme . Napoleons men were hungry for war, as no army of the 1790s had ever been. Virgil, the poet laureate of Rome, wrote in the Eclogues in the peaceful aftermath of the civil wars ended by Augustus, A sad thing is a wolf in the fold, rain on the ripe corn, wind in the trees The time of the wolf had come again. The Grande Arme that descended from the gloom and cold of the Black Forest on the armies of the old order in the last weeks of 1805 were the scions of Virgils wolves, who arrived not gleaming in the sun, but as wind in the trees on an unsuspecting world. They would soon rain on the ripe corn of the Austro-Russian armies, with a hail storm of lead and steel. In that moment before they were unleashed, however, their quality was untested, and the reputation of their leader, unimpressive for all who were not in sway to his propaganda. The blue wolves among them the veterans of thirteen years of war had felt the breath of the Angel of Death many times, usually swathed in the white of the Austrian regulars. Many had never fallen on a fold before. Now, as the Corsican wolf circled his quarry warily, the Austrians began to appear increasingly as sheep in his sharp eyes, as they lumbered along the high river valleys in their white coats. As in Virgils homily, no one saw him coming.

Next page

Next page

NAPOLEON VOLUME 2 The Spirit of the Age, 18051810

NAPOLEON VOLUME 2 The Spirit of the Age, 18051810  MICHAEL BROERS

MICHAEL BROERS  For Bill Speck,

For Bill Speck,