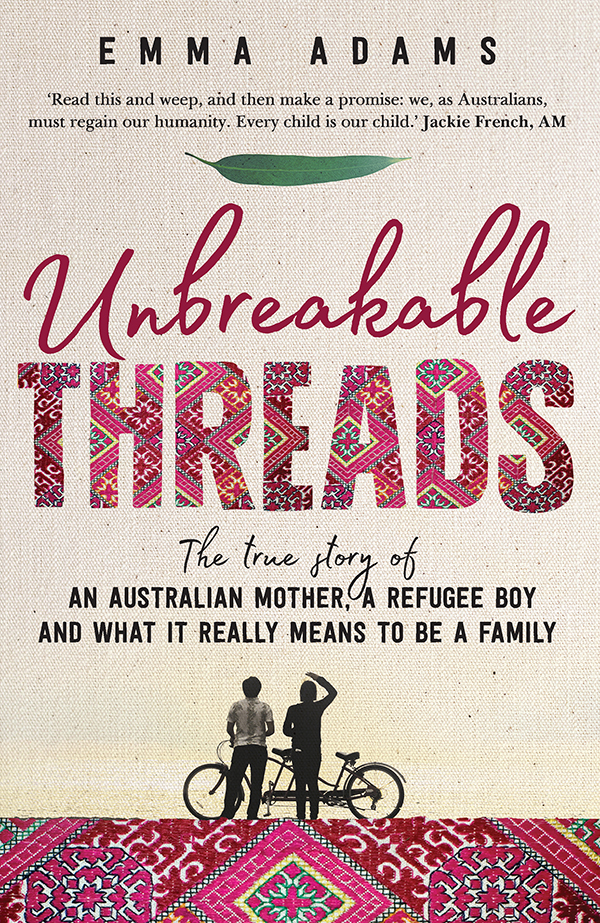

Emma Adams - Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family

Here you can read online Emma Adams - Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Emma Adams: author's other books

Who wrote Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To our parents

First published in 2018

Copyright Emma Adams 2018

The author acknowledges Denise Leith, for her editorial coaching and mentorship

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 310 3

eISBN 978 1 76063 718 7

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Christabella Designs

Front cover photos: J. Marshall / Tribaleye Images / Alamy (Hazara embroidery); Shutterstock

Throughout our lives, the many threads of a story are woven simultaneously. No ones sense of self is constant; instead it is held together within a web of memories and feelings. When two or more people are involved in our story, what happens in the in-between becomes more complex. Who we love and live with changes us. Who we meet and how we interact with them changes us. Love and joy and hurt and loss all change us. Every day, different truths of our selves are revealed. It is only in retrospect that a story can truly be seen. What I knew then and what I know now are worlds apart.

This is the story of how two Hazara brothers, Abdul and Ahad, who fled horrors in Afghanistan in the hope of safety in Australia, came to join our family and how this changed all of us.

I cant presume to tell their story in full as it is not mine to tell, but you will learn something of why they are here in Australia and what happened to them along the way. You will also learn how they came to be part of our family, and how Australias immigration policies affect the lives of not only people seeking peace and safety herepeople like Abdul and Ahadbut of ordinary Australians like my family. For these beautiful Afghan boys could be any of our children.

Our story is told through a patchwork of observations, pictures of our day-to-day life at home, letters, diary entries and Facebook messages, and in this telling I will share with you what I have learned about love, acceptance and the interaction of cultures.

Lovethis most complex of all emotionscan give us more strength and tenacity than we could ever have thought possible.

IMPORTANT NOTE

This book concerns people who are in uncertain situations, who may remain at risk, or whose families are at risk. Although identifying data in many cases has been removed or changed for safety and privacy, the truth of their stories remains unchanged.

We drive 40 kilometres south from Darwin along a flat, scrubby road to reach an isolated peninsula. It is surrounded by swamp and a cluster of buildings sits on a red gash of newly cleared ground. Before we are allowed through the security gates, a guard checks our names, IDs and the purpose of our visit. In the car park, we walk past teetering pallets stacked high with baby baths in mouldering cardboard boxes, while high in the harsh blue sky eagles wheel in the tropical thermals. This is the Wickham Point detention centre complex.

Originally earmarked for mining company accommodation, the place was eventually abandoned because of health risks related to the dangerous number of sandflies and mosquitos. Despite these concerns, the Department of Immigration had recently taken up the lease to accommodate asylum-seeking families.

As we walk across the hot bitumen to the entry point that December of 2013, I try to comprehend what I have been told. Families and over 300 children, including newborn babies, are being held behind that barbed wire. Some children have crossed the sea alone. These are the people I have come to see.

As a psychiatrist specialising in the mental health of mothers and babies, I am here to visit over three days at the request of ChilOut (Children Out of Immigration Detention), a group opposed to the Australian governments practice of mandatory detention of children. I was a last-minute replacement, as the original paediatrician could not make it. My fellow medical traveller is a professor of obstetrics. We have been asked to observe the care and wellbeing of mothers and babies, and the facilities available to them, in immigration detention in and around Darwin.

It is Friday. We are to be given an official tour of Wickham and Blaydin detention centres, both of which are out of town at a place called Wickham Point along Channel Island Road, and then we are to inspect Darwin Airport Lodge, a detention centre adjacent to the airport. At all times today, we are to be escorted by Department of Immigration public servants and staff from Serco, the British multinational company contracted to run the centres. Over the weekend, we will sit down and talk with some of the families that have sought asylum and are now indefinitely detained in this place.

The Serco employees take us to a tea room and give us a security talk. We are told we should use insect repellent and wear solid, covered shoes because of insects and snakes. The same matter of fact tone is used when they talk about the people we are about to encounter inside. When the perfunctory talk is finished, we have our ID checked again, our bags are X-rayed, and after depositing our phones and electronic devices with security were swept by metal detectors. We then pass through several sets of locked gates and are escorted along a grim, narrow corridor of welded grilles and through a double layer of electrified wire perimeter fencing until we are finally inside. I can see shipping containers stacked two high; these are the living quarters of Wickham Point. It is what the government calls an alternative place of detention, or APOD for short. This is supposed to be the family-friendly version. With electric fences, guards and no freedom to come and go, in reality it is a prison.

In the dining room, I notice a male guard because of his body odour. He has his arms outstretched and is blocking the entrance of two young women in modest Muslim dress. Perhaps he thinks he is playing a game, or they find him attractive, because he appears to be enjoying himself, but I can see that these women are uncomfortable. They cant push past him and they cant tell him off. Its clear that this man has all the power. Eventually the young women give him the smile he is looking for and he lets them through.

That this bullying and sexual intimidation is happening so casually and unremarked upon in front of our official group makes me feel uneasy. I cant help wondering what other boundary violations might be happening when no one is looking.

We walk past an isolated courtyard into an accommodation area and I see a small toddler sitting alone in a sandpit. Things are not right here. It is not normal in any culture for babies this age to be just left alone. Where are his parents and why on earth are the people responsible for the care of these children not doing something about his situation? The childs face is blank and his dark eyes stare into space as he repeatedly flicks the handle of a brightly coloured plastic bucket. I cant help but compare this scene with a photograph I have of my eldest son when he was the same age: Jasper is at the beach, his blue eyes alive and smiling back at us as he pauses in his busy digging with a bucket and spade. The child in front of me is not playing. He is helpless; he cant run away or fight this isolation, and since there is no one around to help soothe his distress he has become frozen and dissociated. As we pass by, one of the immigration officials escorting us laughs, commenting how cute this child is. I am appalled that the custodians dont see this gross abnormality.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family»

Look at similar books to Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Unbreakable Threads: True story of an Australian mother, a refugee boy and what it really means to be a family and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.