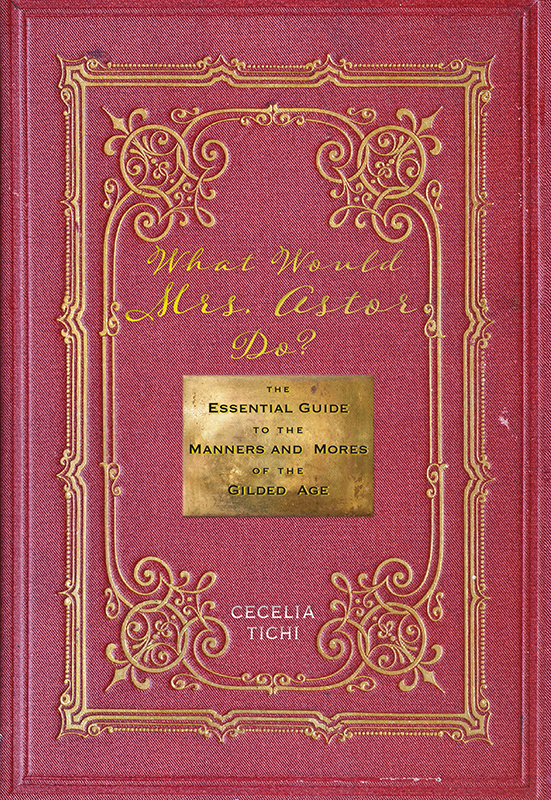

What Would Mrs. Astor Do?

What Would Mrs. Astor Do?

The Essential Guide to the Manners and Mores of the Gilded Age

Cecelia Tichi

WASHINGTON MEWS BOOKS

An Imprint of

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

WASHINGTON MEWS BOOKS

An Imprint of

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2018 by Cecelia Tichi

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-2685-8

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Book designed and typeset by Charles B. Hames

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To the young American, here or elsewhere, the paths to fortune are innumerable, and all open; there is invitation in the air and success in all his wide horizon.

Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age, 1873

Contents

A Black-Tie Dinner on Horseback

Mrs. Astors Annual Ball

Virtues of Free Enterprise

On Philanthropy

Mark Twains satirical novel The Gilded Age, published in 1873, gave name to an era of American history marked by a remarkably rapid industrial expansion, the amassing of great wealth, and soaring national confidence. Spanning the period from the post-Reconstruction era and the rise of Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt to a sobering twentieth-century pivot from Gilded Age glamor to Progressive Era reforms, these thirty years saw the nations population soar from about thirty-eight million in 1870 to over seventy-five million in 1900. (At the turn of the century, the population of New York City alone reached one and a half million.) Across three million square miles of continental territory, the country was transformed from a land of small farms and artisanal workplaces to vast industrial zones, urban arenas of art and culture, and seasonal seaside resorts punctuated with mansion cottages. Gilded Age America became the worlds preeminent and richest industrial nation, and New York City was its epicenter.

Leading figures of the Gilded Age were household names, their comings and goings bannered in newspapers owned by the rival press lords: Joseph Pulitzers New York World and William Randolph Hearsts New York Journal fought a bitter circulation war to captivate an awed public. The famed captains of industry included the father and son Commodore Cornelius and William K. Vanderbilt, the steel king Andrew Carnegie, and the oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller. Wall Streets John Pierpont Morgan became synonymous with high finance and Thomas Alva Edison with electricity. The galaxy of the industrial ultrarich included the copper mogul James Clark, the coke baron Henry Clay Frick, the railroaders Collis P. Huntington and Edwin H. Harriman, and numerous others.

As the sources of the wealth of these men imply, they tapped coal and iron ore, timber and petroleum, copper and precious metals to manufacture a dizzying range of products from steel rails to sterling tableware. Merchant princes, together with shippers and manufacturers, sent consumer goods to and from coastal ports, along the highways of rivers, and increasingly on the railroads that spanned over ninety thousand miles of track by 1880. The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in spring 1869 heralded the establishment of the Union Pacific, Central Pacific, the New York Central, the Santa Fe, and a host of other rail lines that would vein the continent. By 1890, US production exceeded the combined economies of Germany, Britain, and France. With no income tax in the US, personal wealth soared to unprecedented heights. Opulence was the order of the day.

Though hailed as an era of abundance, the late 1800s Gilded Age was marked by intense business and political rivalries. Social rivalries also seethed beneath the gilded surfaces. Not surprisingly, the generations prior to the Gilded Age produced a class of wealthy Americans whose social preeminence was guaranteed by their lineage. Or so they assumed. They were horrified by the new-money parvenus who thought their fortunes earned them entre into late-1800s Societyits formal balls, its debutante parties, its opera boxes, its sailing regattas, its summer gatherings at Newport. To an extent, old money successfully manned its social barricades against the onslaught of newcomers, as if these barbarians (rough, illiterate, vulgar creatures, as one etiquette manual put it) were storming the gates.

Old money could somewhat secure its threatened status by marriage, a strategy dating back centuries in Europe and elsewhere. One celebrated wedding in 1854of the twenty-four-year-old Caroline Webster Schermerhorn to William Backhouse Astor Jr.highlights the consolidation of two such families. Their nuptials joined a young woman whose family traced its roots to the Revolutionary era and a young man whose grandfather was John Jacob Astor (17631848). Her forebears became wealthy from shipping, his from the fur trade.

Caroline Astor became the acknowledged social arbiter of the Gilded Age when a pedigreed, pudgy, and pompous courtier of sorts named Ward McAllister endeared himself to her. He persuaded Mrs. Astor that she, and she alone, was uniquely qualified to uphold the manners and mores of Gilded Age America. Mrs. Astor, known as the mystic Rose, was doubtless also keenly conscious of the vast influence of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, whose long reign demanded that an American of similar influence and stature rise up to challenge it. This power was hers to claim, and claim it she did.

Masked by graciousness, Mrs. Astors steely disposition was the armor she wore as social doyenne of the premier city of the premier nation of the world. Caroline Astor did not invent the notion of proper etiquette. Prior to her marriage, the young Caroline Schermerhorn would have absorbed the proper standards of conduct appropriate to her class. Now, the question What would Mrs. Astor do? became an urgent matter for anyone aspiring to rise in the strict social hierarchy over which she presided. From dawn to the wee hours, indoors or out, whatever the season, Mrs. Astor dictated proper behavior and demeanor, mens and womens codes of dress, acceptable patterns of speech and movements of the body, and what and when to eat and drink. No item of etiquette was too trivial for her adjudication, from the elements of penmanship to the appropriate costume for a game of croquet to the proper slicing of fruit. Regarded with the weight of scripture, Mrs. Astors dictates prompted the publication of a spate of etiquette guides offering nervous readers their keys to initiation into the charmed social circles of the Gilded Age.

As hostess, Mrs. Astor enforced her edicts with a velvet fist. Her scepter she held firmly, absolutely, and charmingly, one socialite remarked. At key moments, nonetheless, the doyenne of Society yielded to social pressure. Old money and new pressed against each other like tectonic plates until 1883, when the rich upstart Alva Vanderbilt (Mrs. William K.) announced plans for an elaborate dress ball at her Fifth Avenue mansion. Snubbed once too often by Mrs. Astor, Alva omitted the Astors from her invitation list. The Astors daughter Caroline Astor, however, looked forward to the Vanderbilt ball, and for Carolines sake, Mrs. Astor summoned her carriage, drove to the Vanderbilt mansion, and left her calling card, whereupon an invitation was issued. The ice was broken, though the mystic Rose ruled supreme for another quarter century.

Next page