GARDEN CITIES AND SUBURBS

Sarah Rutherford

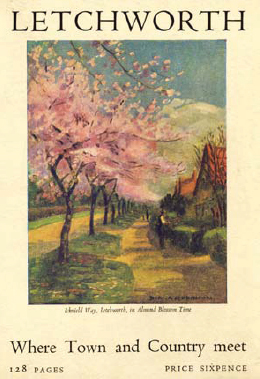

Where Town and Country meet underpinned the Garden City Movement. The publicity material promoted this key aspect of the lifestyle.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

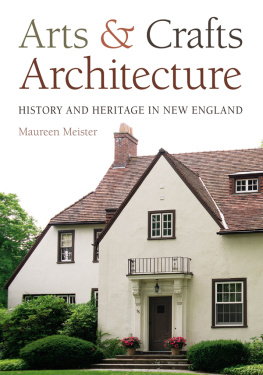

Letchworth Garden City. Typical Arts and Crafts-style housing clustered around a Parker and Unwin village green.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T HIS BOOK covers garden cities, garden suburbs and garden villages. In the early twentieth century these innovative settlements provided a practical solution to decent mass housing in pleasant surroundings, often using the best designers of their day and creating popular, attractive communities. In the early twenty-first century the ethos of the Garden City Movement on which they were founded is still felt worldwide and respected as a valid model for town planning.

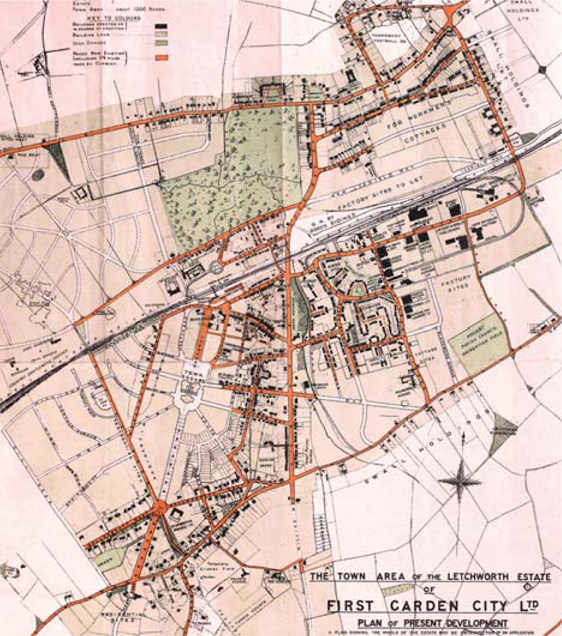

Letchworth Garden City after nine years of development, in 1912. Parker and Unwin arranged the city around Broadway, a broad spinal approach road from the south and north with the Town Square at its heart.

The Shredded Wheat factory production line at Welwyn Garden City, the second English garden city.

These three types of settlements differed in scale. The garden city was intended by its originator, Ebenezer Howard (18501928), to be a large-scale, self-sustaining community laid out in zones to separate various functions. In his book of 1898 (best known under its later title of Garden Cities of To-Morrow), he showed how residential areas could be supported by separate areas for industry to provide employment and economic success. A civic heart included entertainment, local government and shops; there were to be public and private green spaces throughout, and all this within an agricultural setting to feed the community. It was a huge undertaking and only three garden cities were successfully executed in Britain, at Letchworth (1903) and Welwyn (1920), in England, and Rosyth (1915) in Scotland.

The garden suburb was a smaller-scale and more easily established proposition, based on similar principles of good-quality mass housing in spacious surrounds. Crucially it was not the industrially and commercially independent unit first realised at Letchworth. Instead, the garden suburb was part of a larger conurbation, which it served, and in this it was the antithesis of Howards self-sustaining principles. The garden suburb originated in Bedford Park, West London, begun in 1875, and with nineteenth-century industrial villages such as Port Sunlight, Cheshire, and Bournville, Birmingham. While the garden suburb did not have its own factories, warehouses and civic framework, it was more than a dormitory for it usually had a strong social centre, which engendered a community spirit. Garden suburbs are found all over Britain and were embraced on the Continent and in North America, South Africa and Australia.

Welwyn Garden Citys 1920s neo-Georgian style set a precedent for much public housing.

Rhiwbina Garden Village, Glamorgan, waas founded in 1912 near Cardiff to a master plan by Unwin and is the best garden suburb in Wales.

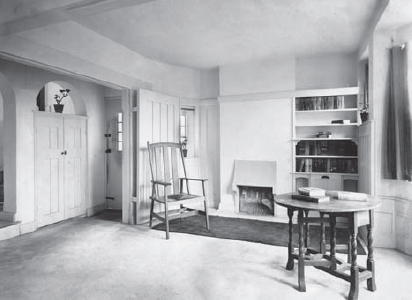

The interior of a house in Gidea Park designed in 1911 by Barry Parker for the Romford Garden Suburb Cottage Exhibition. The arrangement has light and airy white-painted Arts and Crafts interior.

The garden village provided another small-scale detached community, but was designed with an element of economic self-sufficiency. There were varied drivers, such as Whiteley Village, Surrey, for retired persons of small means, Jordans Village, a Quaker craft community in Bucks, and theWestfield War Memorial Village, Lancaster, built to provide employment for disabled soldiers after the First World War. Others were sustained by a factory or industry such as mining, for example Silver End, Essex (for workers at the Crittall metal window factory), the Reckitts garden village in Hull, or the exemplary mining village at Woodlands, Doncaster.

The Garden City Movement, which promoted the philosophy of these planned settlements, quickly developed from 1898, inspired by Howards writings. It became a broader and wider phenomenon beyond Howard and the Garden City Association, in which many of his followers developed his ideas. The Movement was embraced by a range of groups and initiatives working to control or better plan cities and towns that were expanding rapidly and in an unplanned way, to address the mass housing problem in a decent manner, and to improve housing conditions. Various organisations shared similar goals, such as the National Housing and Town Planning Council.

The garden city as proposed by Ebenezer Howard, and during its early years when promoted by the Garden City Association (later the Town and Country Planning Association), was a parallel movement with town planning, then also in its early days. As both were concerned with large-scale planning it was inevitable that their aims and principles coalesced, with the result that the clarity in the single policy of the garden city became blurred among other needs. Even so, the Movement left a hugely influential legacy. This remains dominant throughout Britain, particularly in municipal housing, and in parts of the wider world, even though Howard might not have approved of all its results.

At Whiteley Village, the retirement homes were all built to a very high standard following designs by seven leading Arts and Crafts architects.

Residents were proud of their garden cities. Mementoes even included crested china knick-knacks. This example is from Letchworth.

The ideas of Howard and his followers from the 1890s were vindicated in 1946 with the passing of the New Towns Act. New Towns fulfilled many of the aims of the Garden City Movement, most comprehensively in lower housing densities within the towns, the use of green belts, employment provision, and new towns forming part of the post-war plans. This far-reaching policy was influenced by the Garden City Movement in its drive for self-sustaining and high-quality large-scale new settlements in the countryside, and affected the living standards of many whose lives it sought to improve.