We appreciate that the book you have in your hands is not going to make for very easy reading, as its critical apparatus is longer than the manuscript that was its starting point.

For this reason we venture to recommend that you read Antoine Gimenezs text (and the few footnotes attached to it) through once, and then, if your heart is in it, read it a second time making the forwards and backwards leaps that we suggest to you by means of the endnote numbers placed in bold ornamental brackets throughout the text.

We have written this book the way it pleased us to imagine it being read, which is very selfish of us but primarily reflects the manner in which our research was conducted.

We started off by using the singular testimony from a leading character unknown even in anarchist circles, in order to deal generally with the war in Spain, following the various phases of the Durruti Columns International Group and the many ups and downs of life on the Aragon front.

The endnotes that run from page 207 to page 545 are, on occasion, quite substantial, but our hope is that you will bear with us here, for what is brought to light there is hard to find and, in most instances, beyond the reach of the average reader and sometimes hitherto unpublished.

To complement this battery of endnotes, we have added individual biographical entries, found between pages 549 and 646, which readers are urged to refer to, in that they contain clarifications likely to make the endnotes more readily understood.

The bracketed notations are ours throughout.

Preface

In 1936 I was what is conventionally referred to nowadays as a marginal: someone living on the edge of society and of the penal code. I thought of myself as an anarchist. Actually, I was only a rebel. My militant activity was restricted to smuggling certain pamphlets printed in France and Belgium over the border without ever trying to find out how a new society could be built. My sole concern was living and tearing down the established structure.

It was in Pina de Ebro and seeing the collective organized there and by listening to talks given by certain comrades, by chipping into my friends discussions, that my consciousness, hibernating since my departure from Italy, was reawakened.

Antoine Gimenez

The lines that follow are an invitation to step inside the life of a young Italian, a bit of a hobo, who was toiling in the fields near Lrida when the military coup dtat erupted on July 18, 1936. From the very outset, the reader is gripped by the heady atmosphere of those events of July 1936 in Catalonia, as the military and church structures teetered. Then we follow the narrator as he volunteers for service as a militiaman with the anarchist Durrutis column, newly arrived from Barcelona to wrest Zaragoza from the reactionary coalition. To be more specific, Antoine Gimenez then joined one of the bands of international volunteers that were set up along the Aragon front, long before any International Brigades were raised. This International Group was launched by the Frenchmen Berthomieu, Ridel, and Carpentier.

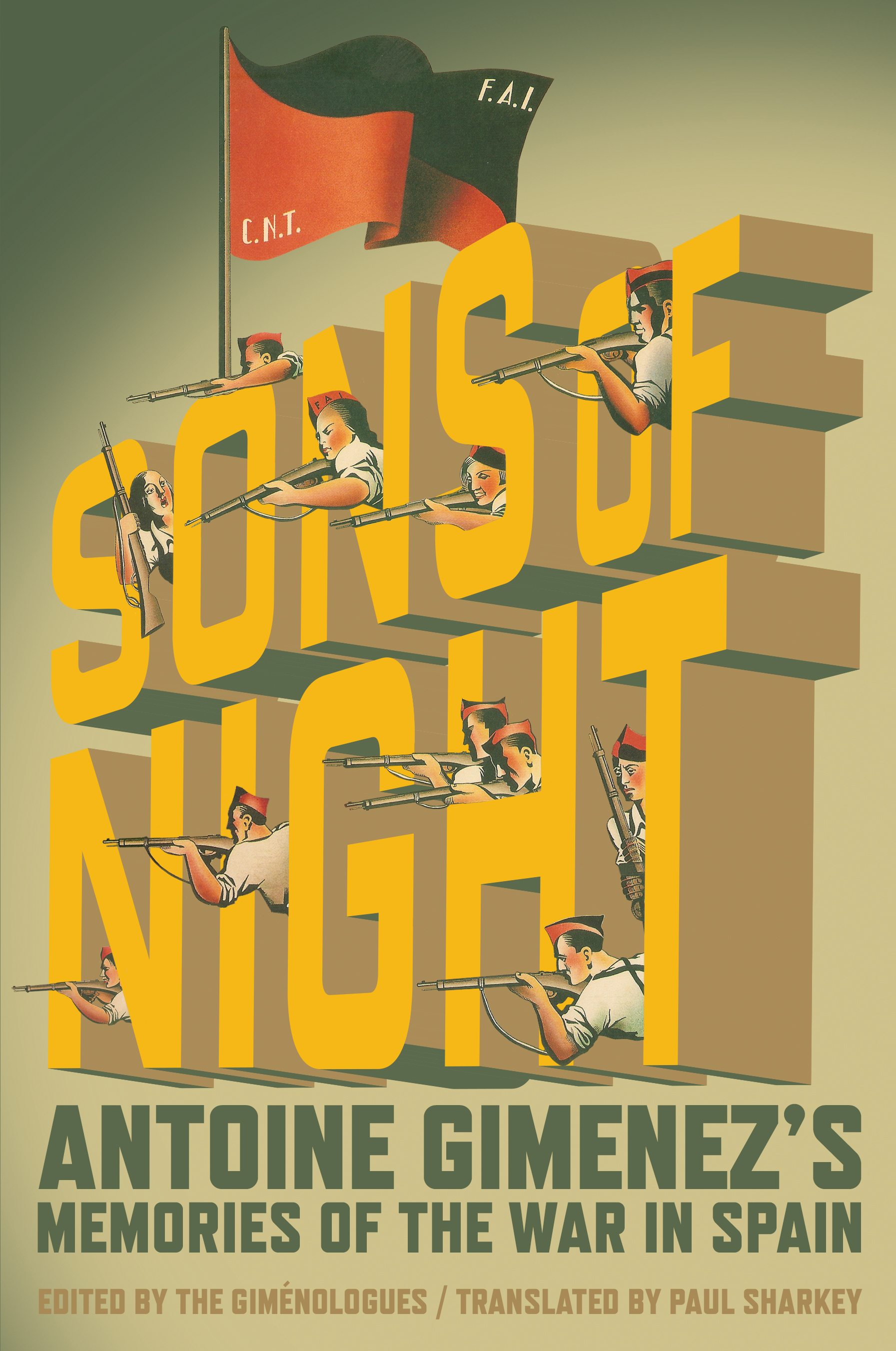

The pace of the writing, the switch from one scene to another, the bitterness of the fighting, times spent with the village collective, the impassioned arguments, the authors personal reflections, the depictions of the male and female militia members, speak of a world turned upside down. What we have here is the earliest document of such comprehensiveness related to the inception and activity of the anarchist militias and, more particularly, to those units of irregulars that were referred to at the time as the Sons of Night.

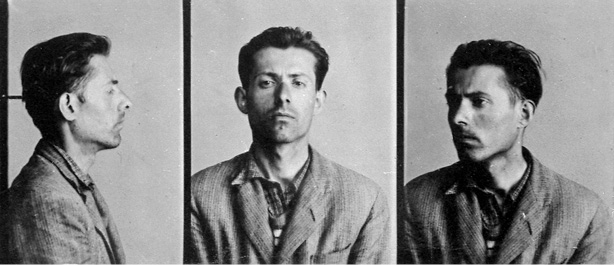

Our Italian, who once upon a time had gone by the name of Bruno Salvadori, offers us a rather original touch as well where this sort of testimony is concerned:

Not for a second does Antoine hold back from incorporating into his account those moments that cannot be unraveled from our everyday lives, like complementary aspects of the revolutionary transfiguration under way at that critical juncture. Just as he regales us with every detail of a meal, so he matter-of-factly recounts his amorous relations, wrote Paco Madrid in November 2004 in his foreword to the Spanish-language edition of the Memories .

This aspect of his writing, as precious to him, we know, as the gaze of his lovers, was to be behind the scandalous contempt in which certain publishers who were approached held Gimenezs manuscript. These old-fashioned prudes in France and Spain, some of them styling themselves libertarians, had the gall to suggest to the author that they might indeed publish, as long as he would agree to the removal of certain scabrous passages.

Like most of the protagonists of the war in Spain, Antoine kept the keynote moments of that experience to himself. He kept his distance from the anarchist movement and over the years penned only short poems and texts. Then in 1974 a thaw set in, and, in order to satisfy the curiosity of his adoptive granddaughter Viviane, he threw himself into the writing of his Memories over the next two years. At the same time, this Spanish-Italian-accented old chap in the beret looked after the premises of Marseilles little libertarian group, premises that were frequented by young folk who, to this day, have fond memories of him. He had this way of capturing their attention with his simple, colorful expositions on anarchist theory, punctuated with his own personal recollections.

Once the manuscript was complete, Antoine had it read by those closest to him before touting it unsuccessfully to publishers, as we have said. When he died in 1982 only a few copies of his Memories of the War in Spain were run off, until the day when the Gimnologues made up their minds to take it upon themselves to publish. They set to work, trying to identify the names of the main characters in his account, starting with the members of the International Group:

The [International] Group was formed prior to there being any question of paying militia members a wage. most of its members had given up their careers and normal occupations to scurry off to Spain. Some came from Italy, like young Giua, others from the Ruhr and the Saarland, some from the political or social underground, like that remarkable burglar from the Romagna who, having resolved to die fighting, put up all of the loot he had amassed in France in order to buy weapons. Mercier Vega, 1975