Copyright 2017 by Jonathan Arlan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Zach Arlan

Cover photo credit: Jonathan Arlan

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-0975-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0976-8

Printed in the United States of America

To my father, brother, sister, and, most of all, my mother.

Beware thoughts that come in the night.

William Least Heat-Moon, Blue Highways

Why then was I attracted to it? There are ideas which link together, flow on and gradually impose themselves.

Gaston Rbuffat, Starlight and Storm

Prologue

I should say up front that, as far as grand adventure stories go, mine is neither especially grandat least in terms of distance travelednor all that adventurous. There are people out there, truly adventurous souls who, for reasons I doubt Ill ever understand, dream up absurdly punishing things to do with their bodies and with their timepeople who cross deserts on foot in 120-degree heat; people who hack their way through jungles while tiny insects eat away at their eyeballs; people who float across shark-infested oceans on rafts; people who, at great personal risk, slip quietly into war zones to report back to the rest of us. I am not one of those people, not by any measurement under the sun; I have no desire to stare death in the eye, to put myself in harms way, to scrape down and find the pleasure on the other side of pain. So while these are the stories I love to read, they are not the stories I can write.

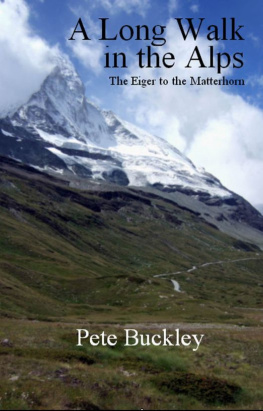

I can write, however, about walkingwhich, Ill admit, may seem a boring subject to most, though not to me. And I can write about a tiny corner of southeastern France; about being outside of my world and wildly out of my element; about pain; about solitude and loneliness and companionship; and, to a small degree, about nature. In a lovely sketch of the Tyrolean Alps, the novelist James Salter writes of a journey that follows a journey and leads one through days of almost mindless exertion and unpunished joy. Hes talking about skiing, but in my mind at least he could just as easily be talking about any kind of traveldriving, or flying, or sailing, or running. Or, why not, even walking.

All of which is to say I can really only write about my own journeya small, slow, low-risk adventure with many days of mindless exertion and a few of unpunished joy, a journey through one of the most stunningly gorgeous and surprising and storied slivers of land on the planet.

It starts like this:

Just as the sun was coming up on a chilly early-August morning, I took the first of roughly one million steps on a walk that would lead me from the southern lip of Lake Geneva, through a large swath of the French Alps, and finally to the Mediterranean Sea, where it would have been impossible to walk any farther. People sometimes speak of moments in their lives when, in an instant, everything changes, and its very possible that that first step was one of those moments. Of course, its also possible that it was just the first of far too many steps on a path I had no real business being on, a path I knew almost nothing about, a path I was totally unprepared fora journey I hadnt earned.

But if you could see it happenif you could watch my right foot fall toward the ground in slow motion and freeze time in the split second before it lands, with the rubber tread of my hiking boot hovering just over the earthyou might see a line, a hair-thin thread of light that, once crossed, will divide my life in two. There is the old me: lazy, indecisive, afraid; and the new: resolute, brave, daring. In a word, adventurous.

Unfortunately, none of this occurred to me at the time. I was far too preoccupied with figuring out (a) what it was I had committed myself to, (b) how I ended up there, alone in the foothills of the Alps, and (c) just how bad of an idea it was to put any real thoughts in any real order. To be honest, what I felt most acutely in that momentand in the days and weeks leading up to itwas dread. I couldnt have pinpointed the origins of that feeling, but it was dread all right, pure and potent and, at times, paralyzing. Its only in retrospect that the scene acquires the glow and gravity of a Profound Moment, a spiritual moment. A miracle, even.

For fun, though, and because memories are endlessly malleable and always changing, here is what it looks like in the syrupy light of my own head: The morning is unnaturally quiet, close to silent, and still, like the inside of an empty church. The cool, fresh scents of the mountain blow by me and I fill my lungs with the buoyant, life-giving air. I take the first step. I close that initial gap between myself and the earth, putting the ground firmly beneath me. I pause. Then I take a dozen more steps. Then a hundred more, and when the number gets high enough, I laugh at my childish scorekeeping, and I stop counting.

The ground is soft from several days of rain and my shoes sink down and spring up with each step. Walking out of the small town where I slept the night before, I see an old man who notices my pack and walking poles and excitedly wishes me bonne chance. I wonder if he knows how far Im going.

On the edge of the woods, a small dog watches me. He holds my eyes for a beat before I turn and disappear into the trees. The knot in my stomach, which has cinched tighter and tighter over the last few days, loosens ever so slightly with each step, like a constrictor finally exhausted from the effort of suffocating its next meal.

Theres an image, tooone I come back to again and again, one (I swear) I actually had in my head at the time: an astronaut. He drifts slowly through space attached to the end of a tether. It looks like hes barely moving, but the cord that connects him the to the craft, to the earth, to everything, is tightening, losing slack. The line stretches and stretches and stretches until, silently, it snaps. Melodramatic? Sure, but thats what it felt like that morning to walk slowly out of a place to which I had no intention of ever returninglike floating.

Or drifting.

Part One

Wandering

When I was a kid, perhaps in first or second grade, I was obsessed with maps. I could stare at them for hours memorizing the names of countries, capitals, rivers, and mountains, trying to cram and hold as many six-point-type details into my head as I could. The way some children can lose themselves in the minutiae of baseball cards, or video games, or stories about magicians and dragons, I could lose myself in maps.

Id start with the big placesRussia, China, Canadaand fill in the blanks. South America was easy with its nice, chunky countries and pretty names. Europe east of Germany was a little trickier, all nervous borders and ever-shrinking republics. And Africa was impossible, too big, too thick with jungles and savannahs and deserts. But every once in a while, all the pieces would click into place, fall together like a jigsaw puzzle, and for short, bright moments I could close my eyes and picture the entire world framed in a perfect rectangle. I knew who shared borders with whom, and where Tibet was, and that there was a place called Elephant Island near Antarctica. I even knew the oceans and seas and lakes, the negative spaces that held everything in its proper place.