Contents

Guide

Page List

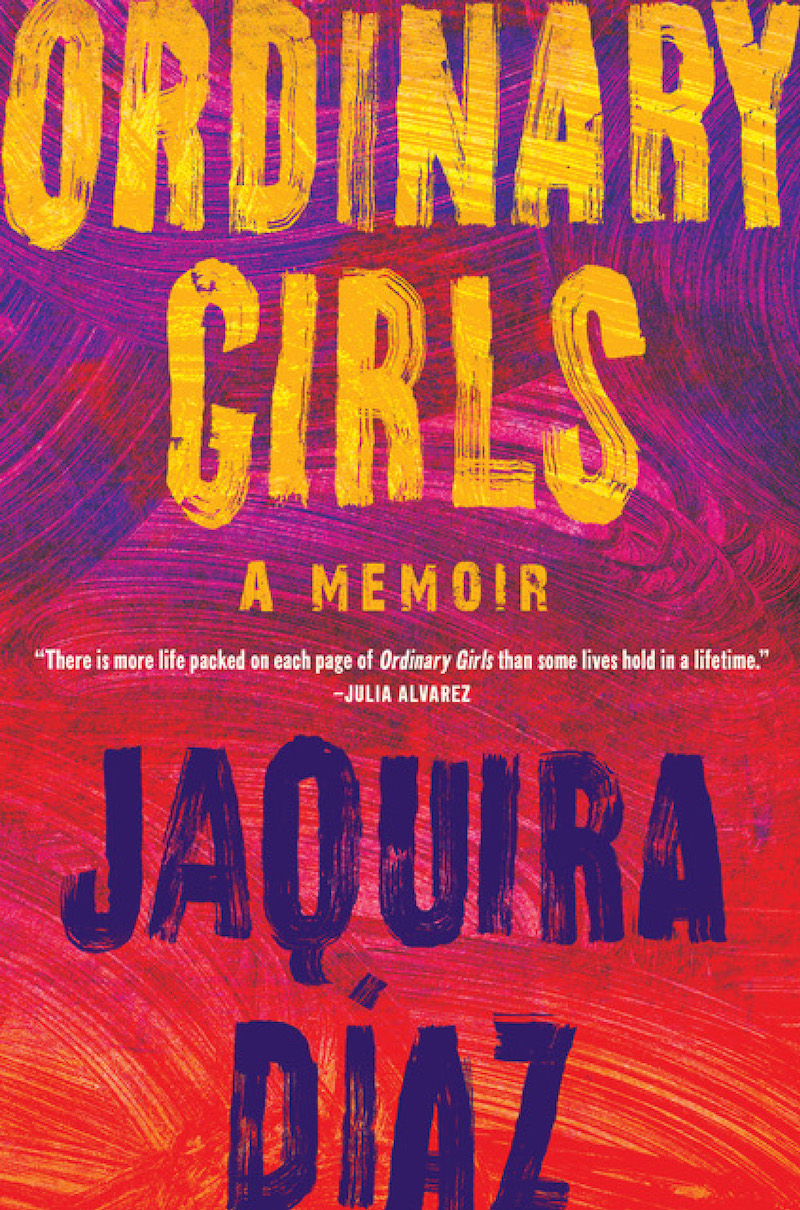

ORDINARY GIRLS

A Memoir

Jaquira Daz

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

Versions of the preceding stories have previously been published as follows:

El Casero, as Malav, in the The Los Angeles Review

La Otra in Longreads

Excerpts of Monster Story, as Baby Lollipops, in The Sun magazine, and as Monster Story, in Ninth Letter

Ordinary Girls in the Kenyon Review and The Best American Essays 2016

Excerpts of Fourteen, or How to be a Juvenile Delinquent, as Fourteen, in Passages North, and as How to be a Juvenile Delinquent, in Slice Magazine

Excerpts of Girls, Monsters, as Girls, Monsters, in Tin Houses Flash Fidelity, and Season of Risks, in The Southern Review

Excerpt of Beach City, in Brevity

Secrets in The Southeast Review

Mother, Mercy, as My Mother and Mercy, in The Sun magazine

Excerpts of Returning, as Bus Ride, 1999, in Juked, as How Memory Is Written and Rewritten, in the The Los Angeles Review of Books, as Inside the Brutal Baby Lollipops Murder Case that Shook South Florida, in Rolling Stone online, and as You Do Not Belong Here, in Kenyon Review Online

This is a work of nonfiction. But it is also a work of memory. Ive researched the story to the best of my ability, and in some cases consulted newspaper articles, court documents, and trial transcripts. Ive changed most of the names and details of friends and family in order to protect their privacy and anonymity. Ive rendered the events to the best of my recallthis is how I remember things happening.

Para Abuela, para Mami, para Puerto Rico,

and for all my girls.

Were going to right the world and live. I mean live our lives the way lives were meant to be lived. With the throat and wrists. With rage and desire, and joy and grief, and love till it hurts, maybe. But goddamn, girl. Live.

Sandra Cisneros , Bien Pretty

Contents

GIRL HOOD

We were the girls who strolled onto the blacktop on long summer days, dribbling past the boys on the court. We were the girls on the merry-go-round, laughing and laughing and letting the world spin while holding on for our lives. The girls on the swings, throwing our heads back, the wind in our hair. We were the loudmouths, the troublemakers, the practical jokers. We were the party girls, hitting the clubs in booty shorts and high-top Jordans, smoking blunts on the beach. We were the wild girls who loved music and dancing. Girls who were black and brown and poor and queer. Girls who loved each other.

I have been those girls. On a Greyhound bus, homeless and on the run, a girl sleeping on lifeguard stands, behind a stilt-house restaurant, on a bus stop bench. A hoodlum girl, throwing down with boys and girls and their older sisters and even the cops, suspended every year for fighting on the first day of school, kicked out of music class for throwing a chair at the math teachers son, kicked off two different school buses, kicked out of pre-algebra for stealing the teachers grade book. A girl who got slammed onto a police car by two cops, in front of the whole school, after a brawl with six other girls.

And I have been other girls: girl standing before a judge; girl on a dock the morning after a hurricane, looking out at the bay like its the end of the world; girl on a rooftop; girl on a ledge; girl plummeting through the air. And years later, a woman, writing letters to a prisoner on death row.

And the girls I ran with? Half of them I was secretly in love with. Street girls, who were escaping their own lives, trading the chaos of home for the chaos on the streets. One of them had left home after being molested by a family member, lived with her brother most of the time. Another had two babies before she was a junior in high school, and decided they were better off with the fathera man in his thirties. Only one had what I thought was a perfectly good set of parents at home: a dad who owned a restaurant and paid for summer vacations abroad, a mom who planned birthday parties and cooked dinner. They were girls who fought with me, smoked out with me, got arrested with me. Girls who snuck into clubs with me, terrorized the neighborhood with me, got jailhouse tattoos with me. Girls who picked me up when I was stranded and brought me food when I was starving, who sat with me outside the emergency room after my boy was stabbed in a street fight, who held me, and cried with me, at my abuelas funeral. Hood girls, who were strong and vulnerable, who taught me about love and friendship and hope.

Sometimes in dreams, I return to those girls, those places. And we are still there, all of us, roller-skating on the boardwalk, laying out our beach towels on the sand, dancing to Missy Elliotts Work It under the full moon.

We are women nowthose of us who are alive, the ones who made it. For a while there, we didnt know if any of us would.

Part One

Madre Patria

Origin Story

Puerto Rico, 1985

Papi and I waited in the town square of Ciales, across from Nuestra Seora del Rosario, the Catholic church. He was quiet, stern-faced, his picked-out Afro shining in the sun, his white polo shirt drenched in sweat. Papi was tall and lean-muscled, with a broad back. Hed grown up boxing and playing basketball, had a thick mustache he groomed every morning in front of the bathroom mirror. Squinting in the sun, one hand tightened around his ring finger, I pulled off Papis ring, slipped it onto my thumb. I was six years old and restless: Id never seen a dead body.

My fathers hero, Puerto Rican poet and activist Juan Antonio Corretjer, had just died. People had come from all over the island and gathered outside the parish to hear his poetry while his remains were transported from San Juan. Mami and Anthony, my older brother, were lost somewhere in the crowd.

During the drive from Humacao to Ciales, Id listened from the backseat while Papi told the story: how Corretjer had been raised in a family of independentistas, how hed spent his entire life fighting for el pueblo, for the working class, for Puerto Ricos freedom. How hed been a friend of Pedro Albizu Campos, El Maestro, who my father adored, the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party leader whod spent more than twenty-six years in prison for attempting to overthrow the US government. How he had spent a year in La Princesa, the prison where Albizu Campos was tortured with radiation. After his release, Corretjer became one of Puerto Ricos most prominent activist writers.

In the car, Mami had lit a cigarette and rolled down her window, her cropped, blond waves blowing in the wind. She took a long pull from her cigarette, then let the smoke out, her red fingernails shining. My mother smoked like the whole world was watching, like she was Marilyn Monroe in some old movie, or Michelle Pfeiffer in