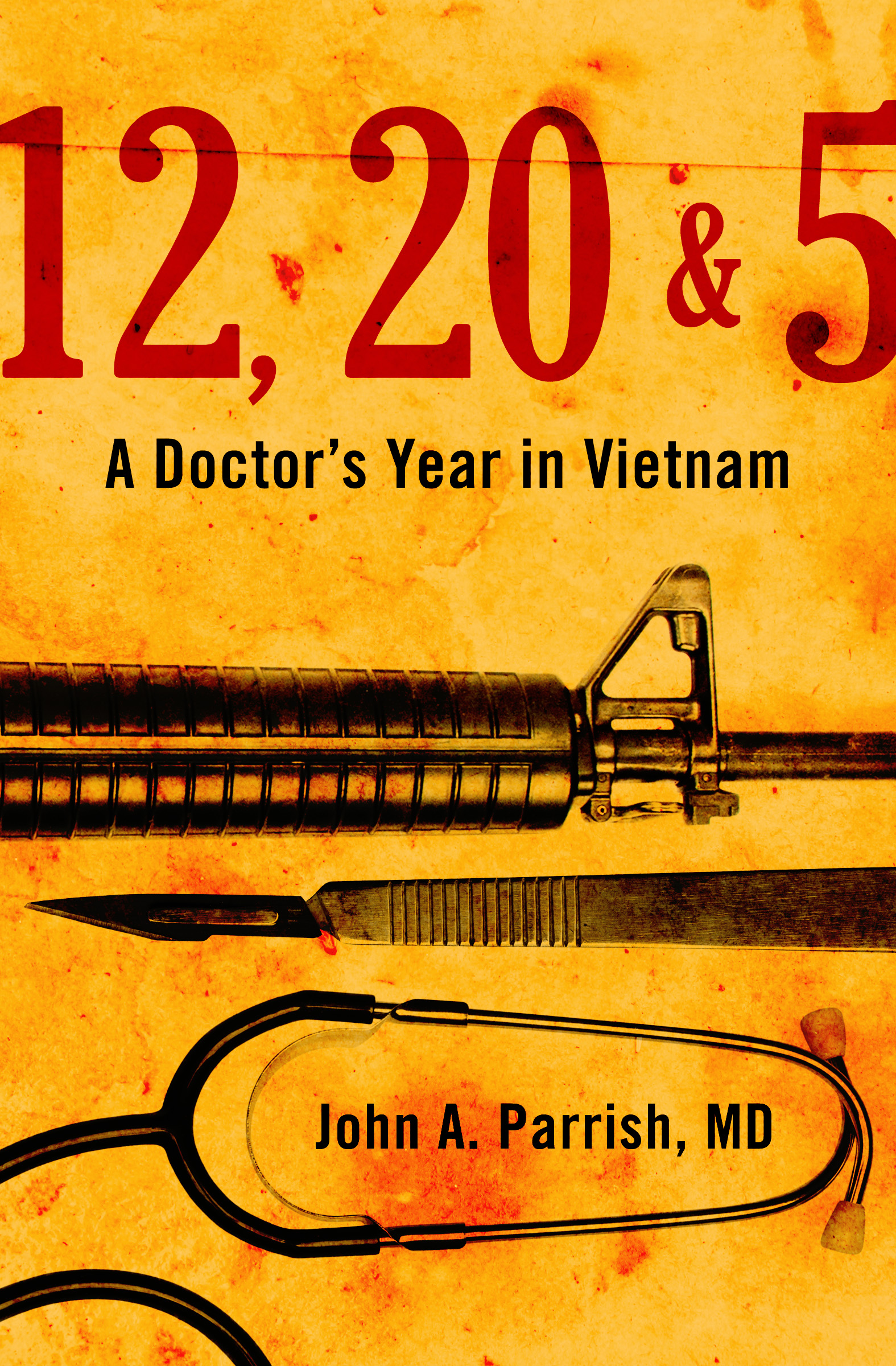

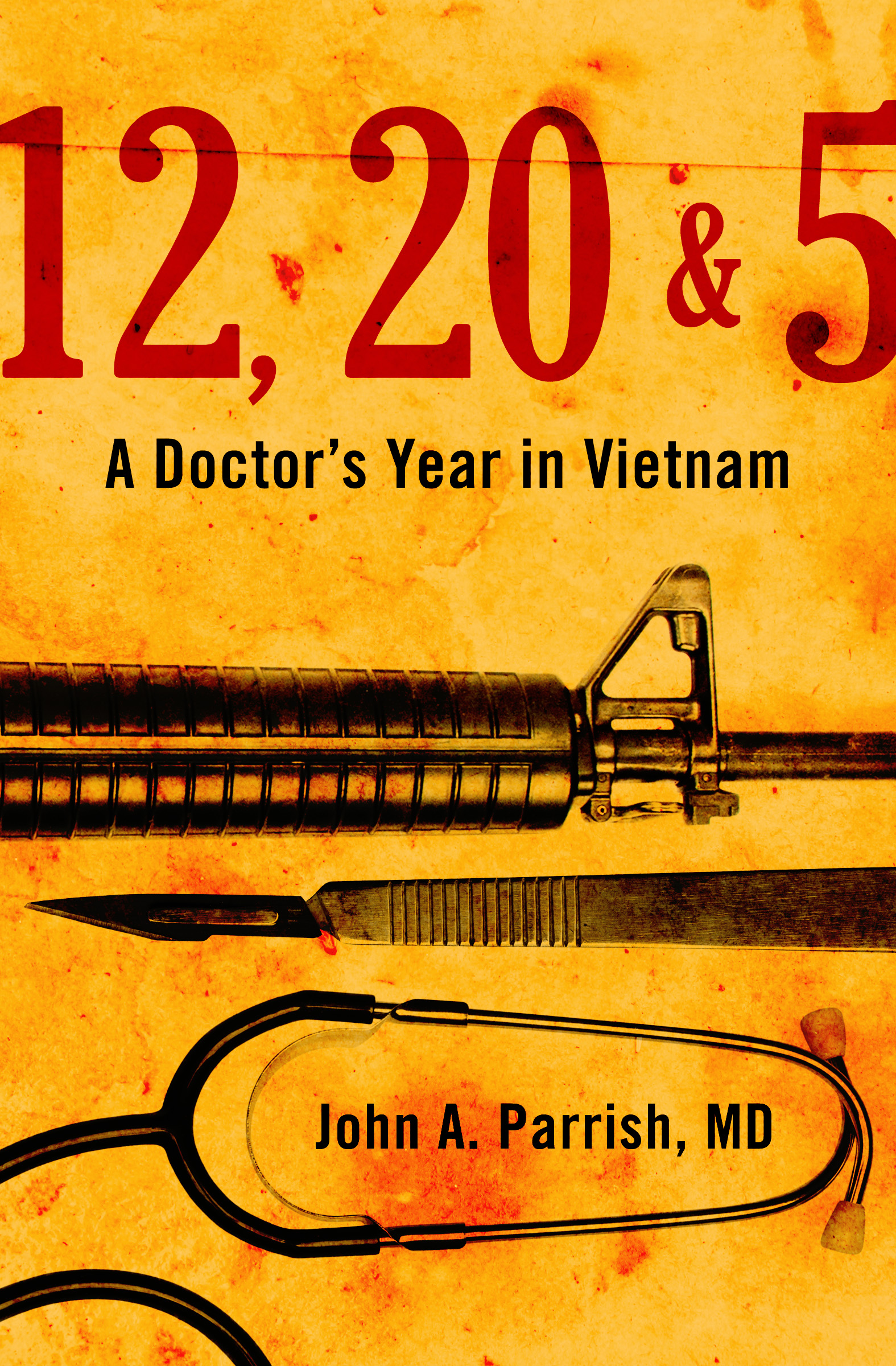

12, 20, & 5

A Doctors Year in Vietnam

John A. Parrish, MD

To Joan

ONE

Tho I walk thru the valley of the Shadow of Death, I will fear no evilcuz Im the toughest mutha in the Valley.

THE SIGN WAS HAND printed beneath a picture of a rugged, unshaven, World War II, John Wayne-type marine with fixed bayonet and fixed stare. The poster was the focal point of a clean, simple, and functional room. The bayonet pointed past filing cabinets and chairs toward a vacant desk labeled Officer of the Day. Three enlisted men draped over wooden chairs looked up with an absence of enthusiasm that told us that our arrival was not making their evening any less boring.

I was beginning my military career by checking in at Camp Pendleton, a marine training base in southern California being used primarily as a staging area for personnel en route to Vietnam. It had been over a year since I received some friendly advice from my government suggesting that I volunteer for a commission as a navy doctor. As added encouragement, the same letter reminded me that student deferment days were over and enclosed a date to report for an induction physical as a 1-A buck private candidate should I choose not to serve my country as an officer and a gentleman.

When I accepted my commission, the navy agreed to permit me to spend another year of internal medical residency training at the University Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan. About halfway through that additional year I found out that my first year in the navy would be spent with the marines in the Republic of South Vietnam. From that point on it was difficult to remain completely enthusiastic about the academic discussions on metabolic or renal rounds, and the collection of esoteric pearls from medical journals seemed somewhat less important.

The obvious good health of the yawning enlisted men scattered about the Officer of the Days room was pleasant in itself. My last few weeks of civilian life had been spent in the hematology service where many of my patients were teenagers dying of leukemia. While investing much of my emotional energy in telling white lies of empty optimism, I had been the helpless observer of the waste and death of the young victims. I was fortunate that my work at the hospital had kept me extremely busy and left me little time for introspection and worry about the future.

During the ten-minute ride from the front gate to our checkpoint I was accompanied by a dentist and another doctor. We quickly sketched in our backgrounds and discussed our feelings about the impending 12,000-mile trip to South Vietnam. The dentist had become the father of his firstborn child three days earlier, and he seemed inappropriately brave, optimistic, and almost happy. The other doctor was an orthopedic surgeon and former football player who did not seem to mind the return to the physical life of an all-male atmosphere. Repairing broken bones and dismembered bodies would be excellent practice for him. Their confidence and excitement made me almost embarrassed about my anxieties over treating badly wounded people and my fears of personal physical injury.

We signed some forms in triplicate with a minimum of conversation. A sleepy marine threw our bags into a pickup truck, and we followed him to an old, two-story, white building. Inside we found thirty or more newly-arrived doctors and dentists in a state of partial undress staking claims on bunks and lockers and nervously making small talk. I found an empty lower bunk near the corner of the large room and began to unpack my new leather suitcase.

What sort of things does one take to a war on the other side of the world? Books? Stethoscope? Candy bars? Sneakers? Sports jacket? Tennis racket? Bathing suit? Jock strap? Camera? Aftershave? I looked over the information booklet about our two week basic training course and counted how many hours of sleep I would get before our orientation session the next morning. It had been dark for several hours, but the California August heat persisted. An upright, slightly dirty water fountain vibrated quietly in the hallway and cradled one hard ball of pink chewing gum in the drain. Four long rows of wooden, double-deck beds were evenly spaced along the worn, but well-polished wooden floor. The room was otherwise empty except for gray metal lockers, human forms, and suitcases.

I took a shower, listened to a few secondhand war stories, and made appropriate small talk with my new neighbors. A transient, slightly nauseating, nostalgic pain in my lower chest made me reach for a cigarette.

The guy in the next bed had the muscle tone of wet toilet paper. His skin was snow white, and his sweaty chest had no hair on it. He talked constantly.

I dont know what the hell they want with me, he complained. I just finished my internship, and Im planning on going into obstetrics. Whats your bag?

My eyes were still scanning the room. Im about halfway through a residency in internal medicine, and I dont know exactly why Im here either. There was no emotion in my voice.

I volunteered to go, said a voice behind me.

I turned to see who Frank Meriwell was, and was surprised to find a reasonable-looking person. He proceeded to tell us at length about American boys getting sick and wounded and needing help. Although it wasnt a very impressive speech, it did cause me to think about the new job I had accepted with a corny little hand-raised oath. It looked as if I were really going through with itI was going to war. Why? How could I justify taking a year from my life to go to a war on the other side of the world?

Immature wanderlust? A search for manhood and excitement? Did I want to be a hero? This war seemed to have no heroes. Was I patriotic? Regardless of my feelings about this war, it was true that American boys were getting sick and wounded. And there must be someone to take care of them. That someone might as well be me. Was my reason for going simply to have gone? To have done it? To experience war? To live through it? To flirt with death and win? Or, perhaps more importantly, to rob death and disease of their victims? Maybe this was my reason for becoming a doctor in the first place. And now I was going to be the doctor in his most trying and finest hour.

Maybe I believed that going to war was the right thing to do. I had been asked to go. It was expected of me. As a child I had learned that being good meant doing what was expected of me; at first by my parents, then by teachers and society. Then by the more mobile but sometimes less flexible superego or God they created for, or passed onto, me.

Living up to expectations was an unusually important part of my life. I was the son of a Baptist minister and a sacrificial, upright, full-time mother. My older brother had died when I was seven, making me the eldest of the remaining three children. My first society beyond the home had been the church. Much was expected of me and I had always made it my business to deliver.

I was a good boy. I silently sublimated away my youth being the quiet achiever. Fair play. Good grades. Nice guy. Hard work. And now war?

Maybe I was still competing. My childhood in Miami with its close, patriarchal family and the comfortable answers provided by religion had been challenged by an interest in science and biology and exposure to a wider range of outlooks at Duke University. My late-blooming ego was threatened. Small successes in the academic world reinforced escape into long nights and weekends of study. The time-limited, goal-oriented, tested, conquest of knowledge and identity seemed to lead logically into competing for a place in a good medical school, and the idea of being a doctor served a reasonable combination of independence and academic life yet leaving room to fulfill the need to serve my fellowman. Yale Medical School had been tough, interesting, and had required almost a full-time effort. Maybe war was another course, a graduate school, an even tougher test. I could compete and achieve and surpass expectations.

Next page