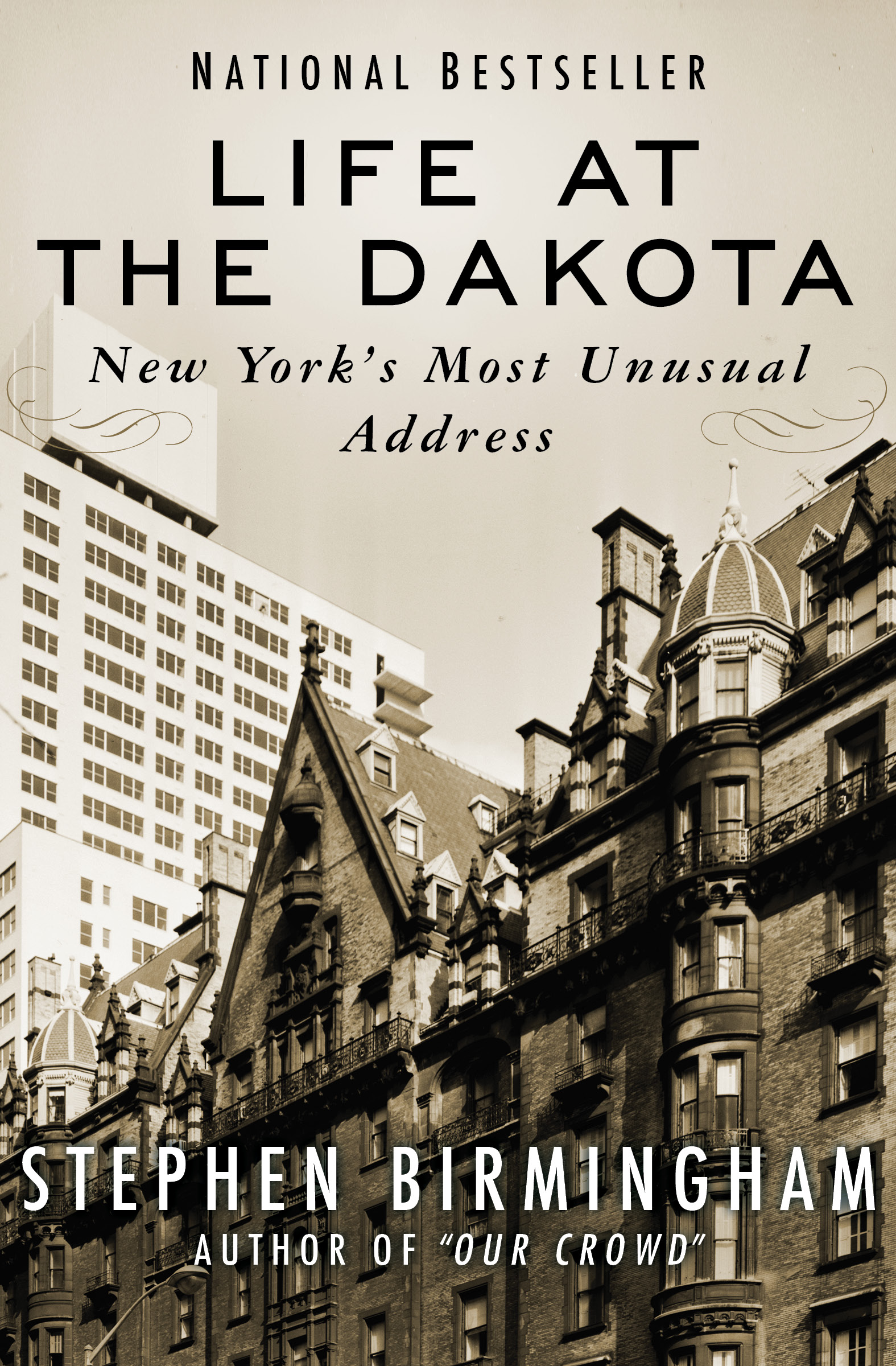

Life at the Dakota

New Yorks Most Unusual Address

Stephen Birmingham

Chapter 1

An Era of Upholstery

Modern New Yorkers have grown accustomed to the experience of going around the corner to what was last weeks favorite delicatessen only to discover that, this week, it has become a wig shop; or finding, where the little place that sold handbags used to be, just off Lexington, that the entire block has disappeared to make room for an office tower. Faced with yet another example of the fact that New York is a restless, ever-changing, never-finished city, New Yorkers simply shrug and go on about their business.

New York in the 1880s was already a city that seemed to have made up its mind that whatever existed was dispensable and replaceable, provided some more profitable use could be found for it. In the years following the Civil War, when great New York fortunes were being madeby men named Rockefeller, Harriman, Gould, Frick, Morgan, Schiff and Vanderbilt, among othersmoney had become New Yorks main industry, while the citys secondary pastime seemed to involve systematically turning New Yorks back upon its past. Anything of even mildly antiquarian or historic interest was the target of destruction, and anyone who deplored the way the city was remaking itself from a sleepy seaport into a bustling capital of finance was regarded as a hopeless sentimentalist. The past was not New Yorks concern; its concern was the future, and Progress. Buildings were flung up only to be torn down a few years later and replaced by newer, more modern structures. Any structure that didnt quite work or didnt quite pay was demolished to make room for something else that might. The modernization of New York, as it marched toward the twentieth century, was as reckless as it was relentless.

Already it seemed that New York was destined to become a city of towers, that it would grow upward as rapidly as it grew outward. In 1884, the year that the Dakota was completed, the architect Richard Morris Hunt had put the finishing touches on a huge new building on Park Row to house Whitelaw Reids New York Tribune. The Tribune tower soared an unprecedented eleven stories into the sky and was topped by a tall campanile, but it was not to be New Yorks tallest building for long. A year later Bradford Lee Gilbert designed the Tower Building, to be erected at 50 Broadway. The Tower Building, which was to occupy a plot of land only twenty-one feet wide, was to rise to a startling thirteen stories, eclipsing the Tribune building in height. The doubters and naysayers confidently predicted that the building would never withstand a high gale. Gilbert was so confident of his structures safety that he announced that he himself would occupy the topmost floors with his offices, but at least one neighbor in an adjoining building evacuated his property, certain that his building would be crushed by the weight of Gilberts when inevitably it fell. In 1886, when the building had reached only ten stories, eighty-mile-an-hour winds struck the city and huge crowds gathered on Broadwayat a safe distanceto watch the Tower Building topple. Gilbert, in a panic, rushed downtown and climbed to the top of his building to see how it was doing. All night long the winds raged, and the Tower Building didnt even tremble. It remained standing until 1913, when it was demolished.

All at once the building of taller and yet taller buildings became a matter of competition. Joseph Pulitzers new building for the World clocked in at fifteen stories and was surmounted with a cupola with a dazzling golden dome. Then came the American Surety Companys tower opposite Trinity Churchtwenty stories high. As New York flexed its muscles for the future, there seemed to be no limit to how high a building could go.

At the same time, while all this building was going on, New Yorkers suffered from what a modern psychologist would label a poor self-image. New Yorkers who cared about such matters, and who had visited such European cities as London, Paris and Rome, were the first to admit that New York was becoming a not very pretty city and disparaged (according to a contemporary account) this cramped horizontal gridiron of a town without porticoes, fountains or perspectives, hide-bound in its deadly uniformity of mean ugliness. The rigid, block-by-block pattern of the new streets that were being laid out was considered boring, and the problem of naming the new streets seemed to have defeated the imagination. They were simply numbered, south to north for the streets, east to west for the perpendicular avenues. Sophisticated New Yorkers complained that their city had none of the exuberance and spectacle of Parisno Place de ltoile, no Place de la Concorde, none of the monumental statuary, arches, bridges and vistas that Baron Hausmann had created. New York lacked the intimate, formal little squares of Londons Mayfair and Belgravia. Instead of a Piccadilly or a Champs lyses, New York had Broadway, and the most that could be said for Broadway was that it was very long. The fashionable area to live was now Murray Hill, on Madison Avenue north of Thirty-fourth Street, where a few years earlier gentlemen of fashion had gone quail hunting, though a few diehard families like the Astors still clung to their mansions on lower Fifth Avenue, between Washington and Madison Squares, even though that part of town was rapidly being taken over by trade. But the houses of the rich, each trying to outdo the others in opulence and splashand built in wildly varying architectural styles from Moorish to English Gothic to Italian Renaissancewere considered pretentious and embarrassing to the purists. New York seemed capable of creating everything but a style of its own.

New York, in the late nineteenth century, was also an astonishingly dirty city for a variety of reasons. Only about half of New Yorks families had bathrooms; the rest were served by outhouses. The Saturday-night bath had become a national ritual, but brushing ones teeth was unheard of. By 1885, some 250,000 horsespulling carts, carriages, trolleys and public omnibusesjammed New Yorks streets. The clatter of horse-drawn traffic up and down Broadway continued night and day. Venturing out into the streets on foot was for the daring, and strollers encountered an obstacle course between piles of steaming dung which swarmed with flies. In hot, dry weather the horse manure in the streets quickly dried to a fine powder and swirled in the air as dust. Ladies wore heavy veils for shopping, not out of modesty or for fashion, but to keep this unlovely substance out of their mouths, eyes and noses. New York horses were driven until they expired, and as many as a hundred horses collapsed daily in the streets. It was often a matter of days before the carcasses could be hauled away, and the odor of decaying horseflesh added its own pungency to the city air. In the 1880s, meanwhile, New Yorkers were only beginning to get used to the luxury of paved streets in certain areas.

Forty-second Street had become the northernmost limit of fashionability; beyond that Fifth Avenue and its adjoining streets had a ragged, unfinished look. Still, though the metropolis consumed less than a third of the area that it does today, New York had already become a city of inconvenient and time-consuming distances. It took a Manhattan businessman anywhere from an hour to an hour and a half to get from his home to his place of work in the slow-moving traffic of the densely congested streets. In 1883, when finishing touches were being applied to the Dakota, the Brooklyn Bridge opened to great civic fanfare, after thirteen years in the building. (Like the builder of the Dakota, the designer of the bridge, John Roebling, would not live to see the completion of his great project.) The Brooklyn Bridge was not designed to appeal to the aesthetic sense. It was without the ornament, spontaneity or romance of bridges that crossed the Seine, the Arno or the Thames. Its beauty was in its stern, no-nonsense practicalitya utilitarian bridge in which every exposed cable slung from the two sturdy towers at either end clearly had a duty to perform: to support the roadbed. The bridge was designed to provide New Yorkers with the novelty, and the convenience, of driving across the East River instead of crossing it slowly by ferryboat. The bridge also dramatized New Yorks need for a public transportation system less cumbersome than the hansom cab and horse-drawn omnibus, and suddenly the phrase on everyones lips was rapid transit.