Contents

Guide

For my family, with love

Lisen Caroline Ma

Kai-Ling Eric Ma

Robert Lewellin Ryan

Katherine Snoda Ryan

Hongshen Ma

Richard Matthew Ryan

A GRATITUDE

Oh, grateful heart,

this is the treasure:

to wander starry-eyed

in a world without measure.

R. M. Ryan

Prologue

I n the United States in 1950, many felt there was something presumptuous about a woman who wanted more than twenty-three-year-old Alice already had. She was a beautiful, dark-haired, long-legged woman with an hourglass figure, a Radcliffe graduate married to a World War II veteran with a Harvard degree. They lived in California, where Alice worked a clerical job to pay the bills while her husband finished graduate school. Theyd both intended to be writers until he found his calling as a literature teacher. Alice still wrote. But she was bitterly unhappy, unfaithful to her husband, estranged from her parents. She developed chronic digestive problemsmuch vomiting obviously psychosomatic, she said.

Alice took half of the doctors advice. She stayed married to Mark Linenthalbut she kept writing. Then she got pregnantand she kept writing. A couple months before the birth of her son, hoping that shed soon have everything she needed to feel happy, Alice submitted the manuscript of a novel to a New York editor shed met through her famous friend Norman Mailer. She and Mark moved to a three-bedroom house in Menlo Park with a study for Mark and a room they painted lemon yellow for the baby. Alice liked the pleasant neighborhood with live oaks and flowering acacias, the huge kitchen, and the nook with a washing machine. I could happily stay here for years, she believed.

A rejection of the novel arrived before the baby.

Alice continued to think of herself as a writer, but her writing became haphazard. Most of the pages she wrote in her notebook during this period are gone, roughly torn out, destroyed.

By the spring of 1958 Alice Adamss inner life was again a turmoil of hopes and memories and confusions. Her mother, with whom she had a frustratingly distant relationship, had died and her father had remarried. She felt profoundly alone. On a cold, windy spring day, in a dressing room at Joseph Magnins department store, she decided to buy some very short white shorts and a full-skirted, bare-shouldered dress with large pink polka dotssummer clothes that were useless in chilly San Francisco.

This time, instead of heeding the psychiatrists advice, Alice took Peter and left California for the house where shed grown up in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She planned to write another novel there, believing that doing so would bring her the money and courage she needed to divorce Mark. Shed avoided that house since before her mothers death, so this was an odd choice, but her motivations were deeper than common sense. She knew her father and his wife would be departing for Maine. Her new clothes made her dream of the smell of jasmine, and the swimming hole in her fathers backyard, of sunshine and warmth. Of not being with my husband. Of, maybe, going to some Southern beach. Of possibly meeting someone. Falling in love.

When he picked up Alice and Peter from the airport, Nic Adams jokingly offered his daughter and grandson slugs of bourbon from a silver flask and talked so rapidly with his pipe in his mouth that Alice couldnt understand a word. The apartment she was borrowing for the summer, a wing of her childhood home, was a shamblesholes in the walls, pieces of floorboard missing. The first evenings with Nic and his wife, Dotsie, were alcoholic, boring, quarrelsome. Already the trip felt like a huge mistake.

Yet in every room stood bowls of the most beautiful, fragrant roses, a welcoming gift for Alice from her fathers neighbor, Lucie Jessner. After Nic and Dotsie drove off toward Maine, Lucie introduced Alice to her friend Max Steele. Max was a writerpublished and award-winning, though currently at loose endswith pale, wide, wise blue eyes, a high forehead, high cheekbones, and a small witty mouthabout to laugh.

Alice felt young and desired again. With Max around, she glided through the summer, happily sure that things would work out. She revised a short story about a love affair shed had in Europe after the wara subtle admission that her marriage was doomed even thenand submitted it to a magazine for women with jobs called Charm.

The summer of 1958 became the endless summer of Alice Adamss life, the interlude that changed her forever. She and Max avoided declaring love for each other, knowing that writers can talk a perfectly good love affair to shreds and tatters. Alices paradoxical and complicated needs were all met in those brief weeks when she had a lover who admired her and encouraged her to write, a mother-figure who praised her ambitions and desire for happiness, and a respite from a marriage she regretted. This uncanny convergence of relationships allowed her to recover her passion for writing. By reoccupying her childhood home, she allowed herself to imagine a new future.

A week after Alice and Max parted with vague plans to meet in Mexico the following winter, Charm purchased Winter Rain. The magazine paid her a then-respectable $350 for that story, enough to allow her to hope that she would easily sell everything she wrote. She made up her mind to divorce her husband.

It would take more than the sale of one story for Alice to get what she needed. Like most women who divorced in the 1950s, she risked poverty; by not staying in the marriage for her childs sake, she also risked being seen as a loose, oversexed woman and a bad mother. Nor was Alice really foolish enough to believe that all her work would sell. She understood that an attractive woman might not be taken seriously in the male-dominated publishing world.

Adams explained what happened that summer in an image: One night while she and Max were walking in Chapel Hill, a pair of twin black cats came toward us out of the darkness, the country nighttwo cats thin and sleek and moving as one, long legs interwoven with each other, sometimes almost tripping. At that we laughed and stopped walking and laughed and laughed, both wondering (I suppose) if that was how we looked, although we were so upright. Then we walked on, hurrying, like people with a destination. The way Alice Adams understood those two black cats in the hot Carolina night as a picture of herself and a man tells us something about the way she saw her destinationthe delights and difficulties it entailed.

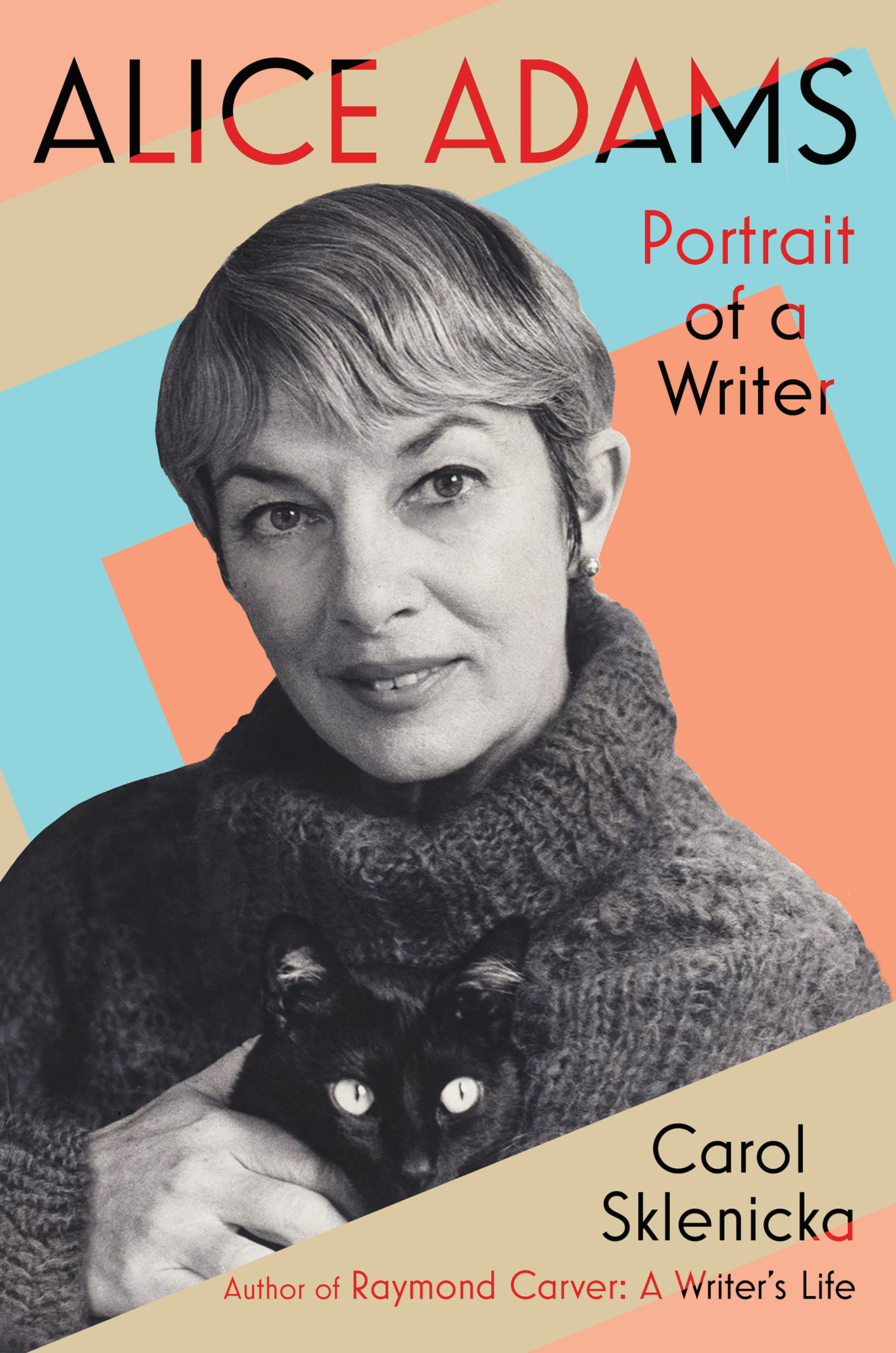

I cant imagine anyone without a very intense inner life full of memories and strange confusions, Adams said after shed published half a dozen books. I was never interested in relationships that werent complicated. I never had a simple relationship in my life. I even have a very complicated relationship with my cat.

She admired the dense novels of Henry James, especially The Portrait of a Lady with its young American heroine named Isabel Archer who wants to choose her own destiny. But Jamess treacherous prose and archaic vocabulary would not serve to describe Adamss characters with their modern ambitions and language. Adams wanted to write beautifully and clearly about the hearts entanglements.

To do that she filled her characters minds with questions, parenthetical thoughts, and feelings that connect with her readers own complex lives. She interrupts her narratives with wise observations like this one from her most celebrated story Roses, Rhododendron: Perhaps too little attention is paid to the necessary preconditions of falling in loveI mean the state of mind or place that precedes ones first sight of the loved person (or house or land). In my own case, I remember the dark Boston afternoons as a precondition of love. Later on, for another important time, I recognized boredom in a job. And once the fear of growing old. Or she jumps about in time and among characters to reveal the workings of desire in two people: Here are Tom (married to Jessica) and Babs, who will marry each other many years later: But they are not, that night, lying hotly together on the cold beach, furiously kissing, wildly touching everywhere. That happens only in Toms mind as he lies next to Jessica and hears her soft sad snores. In her cot, in the tent, Babs sleeps very soundly, as she always does, and she dreams of the first boy she ever kissed, whose name was not Tom.