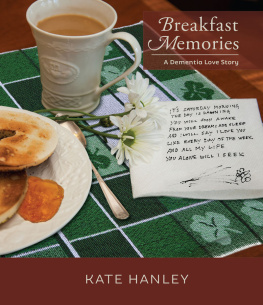

For Mum

Have you asked her if you can write about her? said my writer friend.

Shes dead.

I know. But have you asked her?

Im scared shell say no.

Before I could pluck up the courage, Mum came to me in a dream, wading out of a lake, the hem of her skirt dragging in the mud. You havent forgotten about me, have you? she said.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Dylan Thomas

______

CONTENTS

WHATS THE ONE thing you cant say? asked the voice at the other end of the phone.

Without warning, a picture of my mother filled my mind. Shed been dead for six years, had vascular dementia for almost as long before that. When she started forgetting, she was in her early seventies, a widow, living alone. My four sisters, brother and I rallied round her as best we could while she fought the disease she didnt know she had. It was a sad, bewildering time that tested our certainties and bonds.

The caller was from the 2015 TEDxWellingtonWomen team. Barely back on New Zealand soil from two years overseas, Id been invited to speak at their event and was struggling to come up with a topic. Her question cut through my confusion. The one thing I couldnt say was that I still wanted to write about my mother.

Id been wanting to write about Mum since she died. The decision seemed simple at first. It was my story to tell; Mum wasnt around to veto or be hurt by it. But it was also my siblings story. While some supported the idea, others had misgivings. These were around keeping our mothers memory and memory loss sacred and intact and private. Just like Mum herself, a backroom girl, never one for the limelight.

I mostly believed that putting our experience into words would help my family and perhaps others come to terms with the heartbreak that is dementia. But I couldnt guarantee that. Memoirs tear some families apart. I had hit an impasse: my right to speak out, others for silence. I sensed Mums hand beyond the grave packing me off to Timor-Leste with my husband Pat for two years. Time out to cool my heels. But now we were home and her story continued to tug at my sleeve.

Delving into my past and revealing other peoples lives was not new to me. While Mum had dementia, I wrote Trust, a book about a group of Wellington gang women with whom Id lived and worked in the 1970s. As I struggled with my responsibilities to them and their stories, my tutor told me, Write as if everyones dead and worry about peoples feelings later. Good advice for unleashing creative flow, no use for unpicking ethics.

Ethics were my focus on the wintry May afternoon that I stood in the red TEDx circle in the Wellington City Gallery, sick with terror that my mind would go blank as it had at the dress rehearsal. The thought of my daughter Megan in the 100-strong audience steadied me. I took a deep breath and projected the phrase Compassionate Truth on the big screen behind me. Historian Michael Kings litmus test for biographers came close to my own, I said. Yes, we must be fearless in the pursuit of truth but we must be equally compassionate towards those whose lives we trample through in search of it.

Using my gang women experience, I talked about the power of stories to heal and connect us, but also their potential to re-traumatise even willing subjects and to expose unwitting bystanders. Back and forth I went between the merits and perils of baring our souls, searching for the alchemy between truth and compassion that would make everything all right. The best I could come up with was that comparing notes as honestly as we can encourages us to stand back and reflect on our lives and when we reflect, we find compassion, not just for other people but for ourselves.

Finally I put up a photo of Mum two years before she died, holding her great-granddaughter Avah. Mums head is bowed over the sleeping baby, her crooked fingers cradle Avahs perfect ones. Old life greets new. I acknowledged I wanted to write about Mum and said for now I had to sit with the dont know. My final words were a warning: Proceed with caution. Lives and relationships are at stake when we decide to tell a story, even one we regard as our own.

AS I WALKED offstage, I felt giddy with relief that my memory hadnt let me down. But beneath this euphoria was a growing clarity. The tension between speaking out and shutting up was never going to go away. Not writing about Mum wouldnt solve the angst, just shuffle it around. Somehow the answer lay in the doing of it, fraught and messy as that might be.

I already had the scaffolding for the story: thousands of emails between me and my siblings that chronicled our care of Mum after she got dementia. During this time Id noted down some of my key conversations with her. Even more precious, Id captured her voice on tape reminiscing about her childhood. Letting me record her memories had taken some persuading. She was a listener not a talker; she couldnt imagine why her life would interest anyone else. But when her brother Des came to visit from Adelaide in October 2003, Id pinned them both down.

Even then she was sceptical. If we get a wriggle on we can be finished by lunchtime, she said as I arrived to the smell of fresh coffee and homemade shortbread.

I hope not, I said. Id put aside the whole day for this and was in no hurry to swap the tranquillity of Mums house for the teenage-boy hubbub of my own. I set up my tape recorder at one end of her oval dining table that seated 12 at a squash. Through the sliding doors, a medley of pot plants vied for space on a narrow deck.

Des appeared and wrapped me in an awkward hug.

Who wants to go first? I asked when Mum had cleared the cups.

I go first, she said so unlike her.

Des tipped his head in her direction. Yes. Oldest. At 73, his big sister could still pull rank.

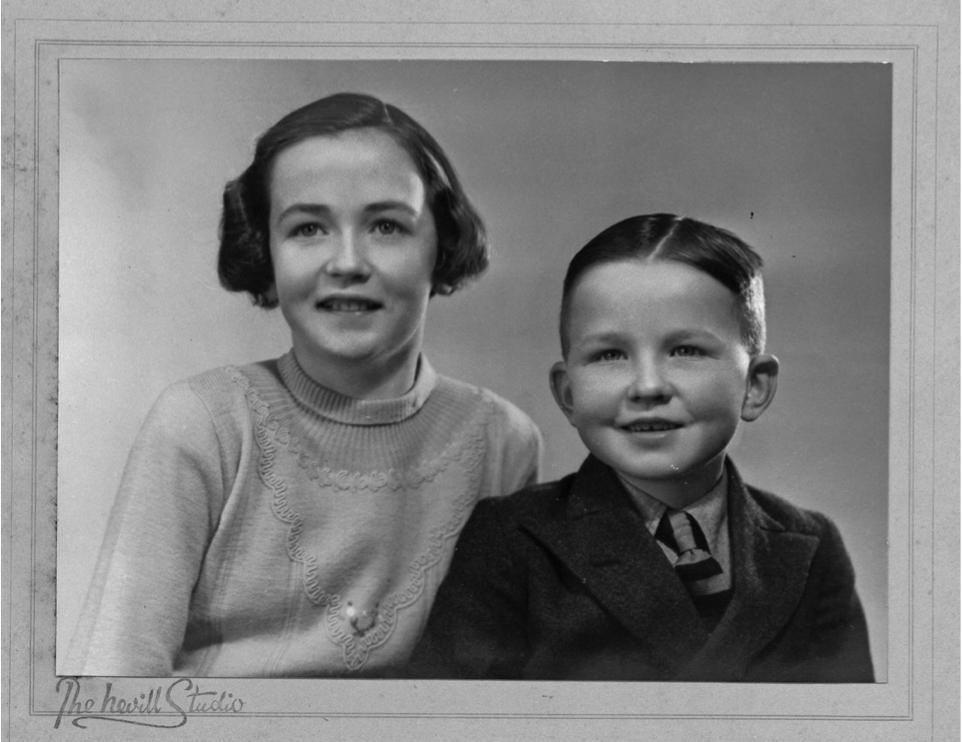

Rosaleen Mary Desmond. Mum gave her married name in clipped vowels, followed by her date of birth: Eighteen eleven twenty-nine. Born in Roxburgh Cottage Hospital. Des came four years later. They had an older half-brother, Gerard, from their fathers first marriage, but he was away at boarding school and didnt figure in their young lives.

As Mum and Des relaxed, a familiar tale emerged: immigrants arriving in Aotearoa New Zealand in the 1860s and 1870s in search of gold, land and a better life. On their fathers side were the Waigths of German and English descent austere, Mum said; on their mothers, the outgoing Kearney clan, Irish through and through. I recognised some of the names from the family tree that Mum had embroidered as a young woman, and which still hung in her lounge.

John Harry Waigth was nearly 50 when Mum was born. Orchardist, mayor of Roxburgh (like his father and brother), a pillar of the Catholic Church, he seemed more like a kindly grandfather to his two younger children. His second wife, Mary Rose, was 20 years his junior and had grown up on a sheep farm in Ranfurly.

Mum, about five years old.