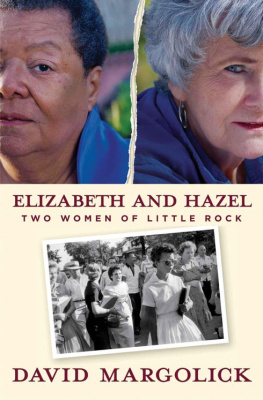

Elizabeth and Hazel

Elizabeth and Hazel

Two Women of Little Rock

David Margolick

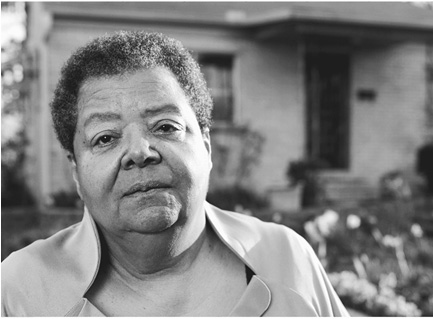

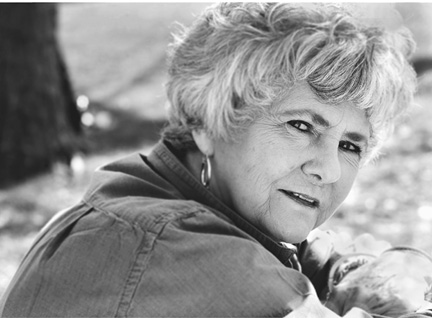

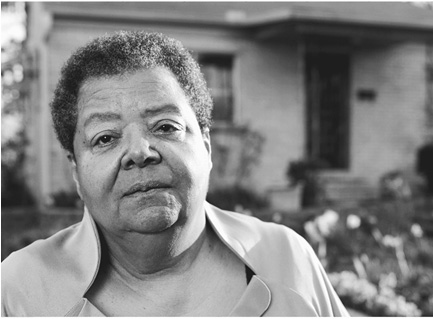

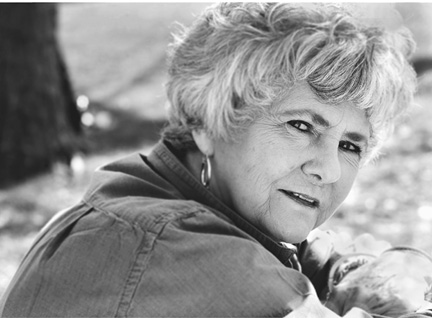

Frontispiece: Contemporary photographs of Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan Massery, photographed by Lawrence Schiller in Little Rock on March 6, 2011;

2011, LJS Communications, LLC.

Quotations from various letters to Governor Faubus, as well as from Benjamin Fine,

J. O. Powell, and Elizabeth Huckaby are used with permission of

Special Collections at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

Copyright 2011 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or

sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Minion type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Margolick, David.

Elizabeth and Hazel : two women of Little Rock / David Margolick.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-14193-1 (hardback)

1. Eckford, Elizabeth, 1941. 2. Massery, Hazel Bryan, 1942. 3. School integration ArkansasLittle RockHistory20th century. 4. Central High School (Little Rock, Ark.)History20th century. 5. Interracial friendshipArkansasLittle Rock.

6. Little Rock (Ark.)Race relationsHistory20th century.

7. Little Rock (Ark.)Biography. I. Title.

F419.L7M37 2011

379.263dc22

2011014101

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my mother, Gertrude Margolick, with love and gratitude

My interest in any man is objectively in his manhood and subjectively in my own manhood.

Frederick Douglass

Contents

Elizabeth and Hazel

Prologue: Two Dresses

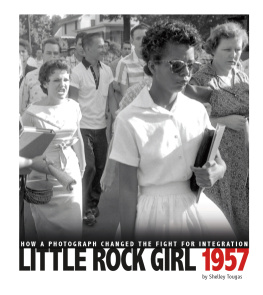

Early in the morning of September 4, 1957, two girls in Little Rock, Arkansas, each fifteen years old, dressed for school.

On a block of black families nestled in the west side of town, in the small brick house she shared with her parents and five brothers and sisters, Elizabeth Eckford put on a skirt that her older sister, Anna, and she had made just for this day. The immaculate white cotton piqu felt cool and soft to the touch; when Elizabeth and Anna, who had labored over it for several weeks, had run out of fabric, theyd trimmed the deep hem with navy blue and white gingham. The new skirts double rows of gathers made it seem to have tiny pleats, and it appeared especially crisp because Elizabeth had ironed it one last time the night before. Buoyed by the petticoat she wore underneath, it encircled her tiny waist like a bellone that rang out the tidings of new beginnings. Fashionable and yet modest, descending well below her knees, the pretty skirt was complemented by the rest of what she had chosen to wear that morning: the plain white blouse (which shed also made), the loafers, the bobby sox. She could just as easily have been going to church, and in a way she was, because for Elizabeth, learning was much more meaningful, and useful, than prayer.

A few miles away, in a house much like Elizabeths but in a neighborhood that was all white, Hazel Bryan selected something very different. It was a sleek dress of cool mint-green, with a triangular white sash at the top pointing suggestively to her bosom, and a ribbon tied provocatively around her midriff. Shed bought it a few months earlier at one of the classy department stores downtown, maybe Blass or Pfeiffers, with around ten of the scarce dollars her mother earned making lightbulbs at Westinghouse. Hazel wasnt signaling the start of an earnest new undertaking so much as making a fashion statement: taking her cues from Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, Elizabeth Taylor, and the other movie stars she followed, Hazel hoped to show off her petite figure, to look older and more sophisticated and maybe more promiscuous than she really was. She wanted to impress her girlfriends, but with any luck the boys forever hovering around her would notice, too. (That the dress was a mite too tight would help.) Shed worn the dress before, probably earlier in the summer. Then again, for Hazel this day wasnt quite as special as it was for Elizabeth. Like all of the white kids, shed begun school the day before, unperturbed by the soldiers who encircled it, and she had been at this particular school for a year already.

Two girls, one black, one white, born less than four months apart, each about to begin eleventh grade. Within a few minutes of each other, they set out for the same destination: Little Rock Central High School. They did not know, norin the world of the South in the 1950swould they have ever encountered, each other before, except perhaps when they rode the same buses or passed on a downtown street or saton different levelsin a local movie theater. But within an hour or so they would, and from that moment on, their lives would be inextricably intertwined. For long after thatas long, in fact, as the tortured saga of relations between the races, in the United States and everywhere else, still mattered, or as long, when it came right down to it, as people can seethey would be linked.

When Hazel got home that afternoon, she took off the dress and changed into something more comfortableboys jeans, perhaps; they didnt yet make them for girlsand hung it up for the next time. Doubtless, there would be many next timesdances, dates, more school daysto put it on. But when Elizabeth removed her skirt that night, then folded it up and handed it to her mother, she already knew she would never wear it, or even want to see it, again. As everyone else was coming to recognize itfor a time, that simple cotton skirt was just about the most famous piece of clothing in the worldElizabeth set out to forget about it. It promptly went into the attic, and no oneElizabeth includedever laid eyes on it again.

ONE

Elizabeth Eckfords house sat on a short stretch of West 18th Street, just off Peyton. Everything about the building and the land it rested on was compact, as if someone had sat down and figured out the smallest and most inexpensive way to fulfill a dreama place of ones own. The home was squat and square, with two bedrooms on a single floor, along with a crawl space below and a small attic, accessible only via a ladder. The place was rudimentary, unfinished: the pine floors, for instance, had never been varnished. The front yard was tidy, and tiny. There was room for a small garden, or a lawn, but not really enough for both, and certainly not enough for a tree. No one had ever bothered with the backyard, where a big rock stuck out of the dirt. A local black doctor, whod grown rich performing abortions and speculating in real estate, had built it in the late 1940s, and the EckfordsElizabeths parents, Oscar Jr. and Birdie; her older sister, Anna; and her younger brothers, Oscar 3rd and Boldenwere the first folks ever to live there, moving in on Elizabeths eighth birthday in October 1949. That was a time, shortly after World War II, when if you scrambled enough, even the relatively poor could own their own homes. The house had grown with the family: as two more children, Melbert Don and Katherine, had come along, the Eckfords had added a couple of rooms to the back.

Next page