Copyright 2018 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-68226-047-0

eISBN: 978-1-61075-624-2

22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Liz Lester

This project is supported by a social-justice advocacy grant from the Second Presbyterian Church in Little Rock, Arkansas, by an African American Heritage grant from the Arkansas Humanities Council, and by the Gordon and Izola Morgan Publication Fund.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941941

This book is dedicated in memory of my parents, Louis Anthony and Ruby Jewel Fleming Bell. My mother, in fact, asked me to do so long ago. It took me some time, however, to consider the fact that this topic might have meaning and value for others. Im therefore grateful that my parents encouraged me to tell the story.

This book is also dedicated to my children and their spouses, to my five wonderful grandchildren, and to the entire Bell and Fleming family clan for your tireless support and love you send from generation to generations of family. Thank you for being and doing family.

FOREWORD

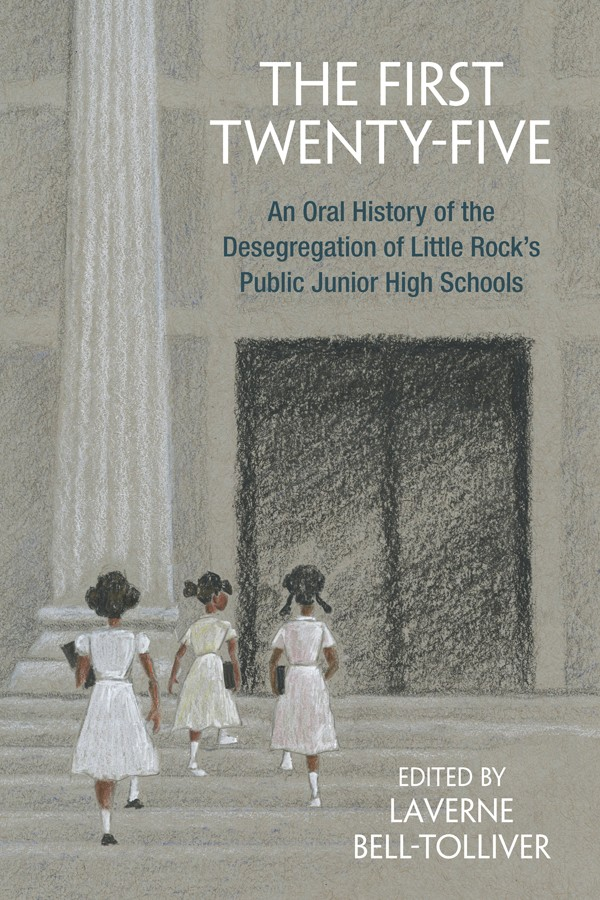

Dr. LaVerne Bell-Tolliver has rescued from the memories of eighteen African Americans their experiences desegregating junior high schools. A half century ago they were the first African American students to enroll in five previously all-White junior high schools in Little Rock, Arkansas. They were called on to break down long-standing racial barriers while in their early teen years, a developmental stage that for most youth brings major emotional vulnerability.

In contrast to the experiences of the Little Rock Nine, who were the first to cross the color line at Little Rock Central High School, the enrollment of these junior high teens received little media coverage at the time, and since then their experiences have received little attention by scholars. Although these young teens had good academic records, which were one reason they were selected by school officials for their trailblazing roles, they were babes in the woods surrounded by the wolves of centuries-old racial prejudice and discrimination.

In the case of the young LaVerne Bell-Tolliver, she did not volunteer for the role at Forest Heights Junior High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Her parents made that decision, which separated her from Paul Dunbar Junior High, an African American legacy school, where she would have enrolled with her friends.

I am especially pleased to read LaVernes story because I was one of the first, along with eighteen to twenty faculty and staff colleagues at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, to ever hear LaVerne tell it publicly. LaVerne was like war veterans and others who have suffered trauma but do not talk about it, do not want to talk about it, are afraid to talk about itbut who need to talk about it, for the sake of the rest of us as well as themselves.

In 2007, I sent a message across campus that I would like to talk with a group of faculty and staff members about the economics of race. We did not finish the discussion when we first met, so we decided to meet again the following week. The Monday afternoon meetings of this voluntary group continued into my final year as chancellor in 20152016. The twenty or so who showed up for the first meeting evolved into the Chancellors Committee on Race and Ethnicity. In weekly meetings, this group covered a multitude of subjects and events related to race and also developed the plans for the UALR Institute on Race and Ethnicity. Everyone in the group learned immensely from each other. LaVerne Bell-Tolliver was a charter member of this group and one of its major contributors. It was with this group that she first publicly shared her Forest Heights story. All of us listening to it knew we were hearing a significant story and were honored that LaVerne was willing to share it with us.

LaVerne Bell-Tolliver today is an adult of faith, impeccable character, and dignity. She also is a person with passion to do whatever she can to move the community and country forward toward the beloved community, the more perfect union. In her chosen profession, social work, she has worked with stressed families and persons who were suffering and confused and isolated and silenced as a result of their circumstances, or their own choices, or both. She and the other children whose stories appear in this volume were put through the fire themselves, and they survived, and in different ways they have thrived in showing others how to make a difficult human journey.

The reader will encounter similarities and differences in the experiences of eighteen young teens that will provide the stuff of reflection and of better understanding as people of goodwill try to bring along their fellow citizens in the ongoing struggle for racial equality and justice.

This volume is rich in information and insight into what was going on fifty years ago in the desegregation of schools across the country. What one sees in the experiences of these eighteen students is that the schools, specifically school officials charged with desegregating the public schools, were not prepared for it. The school administrators were not prepared. The teachers were not prepared. The White students were not prepared. The African American students, one can infer from this volume, were the best prepared, thanks to families and churches and civil rights organizations that wanted them to succeed. Yet they were not prepared either for the circumstances they would face.

Outside of school, LaVerne had a solid family and a caring church. Inside school, LaVerne was without friends in what for her was a cold place. She was socially and physically isolated, with teachers who made her feel conspicuous and who at the same time acted as though she was not in the classroom. Eventually it was in music that she found a voice.

For all of the eighteen African American students, their experiences were confusing, hurtful, belittling, sometimes frightening, and silencing. Going through the experiences and surviving them made them stronger, but they also incurred wounds that are not likely ever to heal completely. We should thank LaVerne Bell-Tolliver and all of the eighteen for telling us what it was like, as children, to be on the very front lines of the Civil Rights Movement. We must salute them for not becoming so discouraged and embittered that they could not handle adulthood and fight the good fight for racial justice.

Joel E. Anderson

Chancellor-Emeritus

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Im so grateful to these former students who shared their stories. They have filled in many gaps in information. News articles, school board records, and even court documents can only supply certain amounts and types of information. These former students were invaluable in explaining their ideas of how certain things, such as the selection process and their decisions about desegregation, took place. They shared their memories, their emotions, and their hopes for the future. Thanks, all of you courageous people!

I also wish to thank the contributors to this book: John Kirk and Vicki Lind, both of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR). When I think of my own experience as a young person who entered an otherwise all-Caucasian junior high school, my memories, questions, and feelings could easily overwhelm the experiences of others. For that reason, Im grateful to have these cocontributors on board to assist with the entire project. Their objectivity about this material allowed richer meaning and themes to come forth than what might otherwise have been seen through my eyes. Thanks is also extended to Charles Johnson and Carolyn Scribner, both of whom were members of the 1962 class of West Side Junior High. Charles helped me to locate at least six of the eighteen members of the first twenty-five, and Carolyn requested to be interviewed. Because the length of this current manuscript exceeded my opportunity to include her information into this book, her transcript may be found at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.