ALSO BY MODRIS EKSTEINS

Theodor Heuss und die Weimarer Republik

The Limits of Reason: The German Democratic Press

and the Collapse of Weimar Democracy

Nineteenth-Century Germany: A Symposium

(edited with Hildegard Hammerschmidt)

Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age

Walking Since Daybreak : A Story of Eastern Europe,

World War II, and the Heart of Our Century

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2012 Modris Eksteins

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2012 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, and simultaneously in the United States of America by Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

www.randomhouse.ca

Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Eksteins, Modris

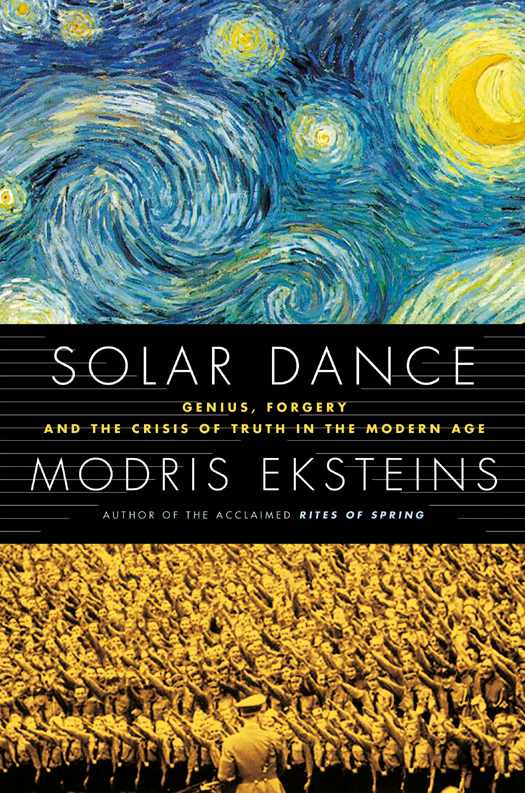

Solar dance : genius, forgery, and the crisis of truth in the modern age / Modris Eksteins.

eISBN: 978-0-307-39861-1

1. History, Modern20th century. 2. World War, 19391945Art and the war.

3. GermanyHistory20th century. 4. World War, 19391945Influence.

5. Civilization, Modern20th century. I. Title.

D424.E47 2012 940.5 C2011-901910-8

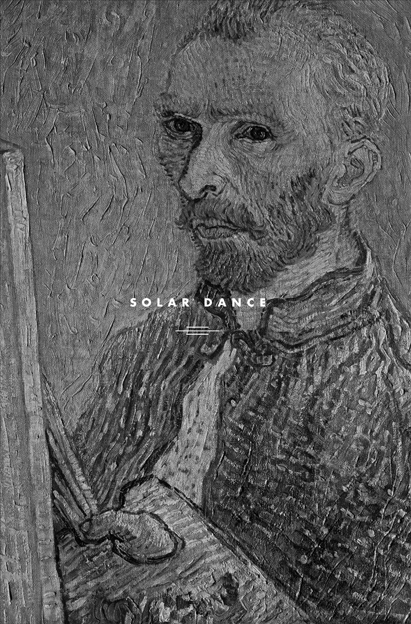

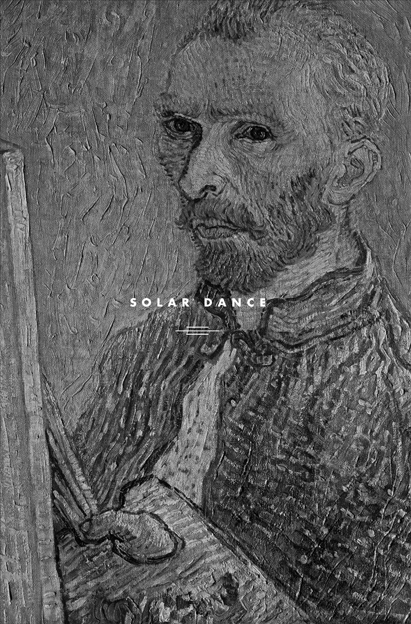

Cover images: Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889. Photo CORBIS.

Hitler Youth Rally, 1938. Bettmann / CORBIS

v3.1

For

AS

and her art of being

CONTENTS

PART ONE

THE PALETTE

PART TWO

THE PERSPECTIVE

PART THREE

THE PAINTING

PART FOUR

THE RESPONSE

PART FIVE

THE EFFECT

THE ISSUE

my great desire is to learn to make such inaccuracies, such variations, reworkings, alterations of the reality, that it might become, very welllies if you willbuttruer than the literal truth.

VINCENT VAN GOGH

to his brother Theo, 1885

V incent van Gogh is the most popular artist of all time. Today he is everywhere: posters of his paintings are on every other student dormitory wall; Singapore and Shanghai banks bear his name; his self-portrait appears on gin and vodka labels; and Australian oilfields borrow from his renown. Yet during his own life he was almost completely neglected. Not only was he neglected, he was despised as both man and artist. How do we begin to explain this turnaround in perception, where the former failure has become our champion?

If every age chooses its heroes as reflections of its priorities, then our fascination with Vincent van Gogh tells us a good deal about ourselves. First and foremost our interest points to the remarkable reversal that marked the past century, whereby a previous misfit could be transformed into a victor. We know about the world wars, the First and the Second, and their devastating violence. We pay less attention, however, to the violence of the mind that produced, accompanied, and followed those wars. The story of Vincent van Goghs posthumous success documents that turbulence, nourished as it was by a mounting public anger against established norms and a corresponding appeal of elemental sensation and spiritual quest. In the end Van Goghs greatest brilliance may have been his doubt. That doubt now pervades our entire enterprise.

Whereas Van Gogh plunged ahead of his own time in the nineteenth century, an age of laws and absolutes, the later era saw in him and his art the vital personification of its own regret and confusion. In his personal development, in his search for transcendence, Van Gogh turned from religion to art; our own time has followed a similar trajectory, turning art into a religion and, in the process, Van Gogh into something approximating a saint, a strangely demonic saint to be surewhat we currently call a celebrity.

It was in Germanya Germany defeated, democratized, and demoralized after the Great Warthat these tendencies first surfaced strikingly. Though the cost, human and economic, of the struggle had been staggering, the French and the British could at least say they had won the war. The Germans had lost, but they found it impossible to admit, much less confront, the idea that their superhuman effort and millions of casualties had been in vain. A process of denial and reversal set in. Defeat was turned into victory, despair into exhilaration, the critic into the enemy, and, within the difficult darkness, the ancient sun symbol that was the swastika emerged ubiquitous in sundry military and political formations. As the black icon of the Nazi Party, an upstart political movement surging in popularity by the end of the 1920s, it would become in 1933 the pre-eminent symbol of a Germany reborn as the Third Reich. Through Adolf Hitler, the Fhrer who had survived four years of war in the trenches, the victim returned as conqueror, the misfit as model, the artist as leader.

Simultaneously, Vincent van Gogh became, as one critic put it, the marker for this new age. His personality and his art merged, the one inseparable from the other. A man defamed and ridiculed during his own lifetime became for many a paragon. Prices for his art soared. Yet the meteoric success of Van Gogh in the 1920s, three decades after his death, might not have happened as dramatically had not another manifestation of reversal transpired, the arrival on the scene of another nobody, another man without qualities, a dancer turned art dealer, Otto Wacker. Without formal training in anything, let alone dance and art, Wacker took Berlin by storm as a stage performer and art dealer. In the middle of the 1920s he persuaded a gullible worlda world much like our ownthat he had a cache of hitherto unknown Van Gogh paintings. The new works were authenticated by the experts and snatched up by collectors and galleries in a wash of excitement. But gradually questions began to surface. Wacker was eventually put on trial for fraud and found guilty, though the source of the pictures was not and never has been determined.

Otto Wacker is in many ways a symbol of the Weimar Republicthat frenzied fourteen-year experiment in democracy that came between the end of the Great War and Hitlers assumption of power. He represented Weimars volatility and aspirations, its energy as well as its fate. His story is worth telling because many of the issues confronting Weimar remain issues for us today as wellabove all, the question of what is true and what is real. The crisis of Weimar marked in many respects the onset of our own crisis, where, as on Pinocchios Pleasure Island, art and entertainment have blurred, where information and disinformation have become difficult to separate, where mundane reality and gleaming image often pretend to be the same.