A Mariner/Peter Davison Book

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

BOSTON NEW YORK

For Theo, Roland, Oliver, and Andra

First Mariner Books edition 2000

Copyright 1999 by Modris Eksteins

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site: www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eksteins, Modris.

Walking since daybreak : a story of Eastern Europe, World

War II, and the heart of our century / Modris Eksteins

p. cm.

"A Peter Davison book."

Includes index.

ISBN 0-395-93747-7

ISBN 0-618-08231-x (pbk.)

1. Baltic StatesHistory19401991.

2. Eksteins, Modris. I. Title.

DK 502.74. E 39 1999

947.9dc21 99-17856 CIP

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Robert Overholtzer

QUM 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Prologue

1 The Girl with the Flaxen Hair

2 A Man, a Cart, a Country

3 Baltic Battles

4 Displaced

5 Bear Slayer Street

6 Odyssey

Acknowledgments

Concordance of Place Names

Notes

Index

Prologue

History is the most dangerous product evolved from the chemis

try of the intellect. Its properties are well known. It causes dreams,

it intoxicates whole peoples, gives them false memories, quickens

their reflexes, keeps their old wounds open, torments them in

their repose, leads them into delusions either of grandeur or per

secution, and makes nations bitter, arrogant, insufferable, and

vain. History will justify anything.

PAUL VALRY

History is not truth. Truth is in the telling.

ROBERT PENN WARREN

There is no such thing as wasonly is.

WILLIAM FAULKNER

SHATTERED CITIES . Smoldering ovens. Stacked corpses. Steeples like cigar stubs. Such are the images of Europe in 1945, images of a civilization in ruins.

At the end of the fury that was the Second World War there was stillness. Alan Bullock, the British historian and biographer of Hitler, recalls traveling to the center of hell at the end of the war: "I remember going to the Ruhrthis was the heart of Europe as far as industry was concernedand there was silence everywhere. There wasn't a single smokestack. There were no cars, no trains."

However beyond the corpses, beneath the rubble, there was life, more intense than ever, a human anthill, mad with commotion. A veritable bazaar. People going, coming, pushing, selling, sighingabove all scurrying. Scurrying to survive. Never had so many people been on the move at once. Millions upon millions. Prisoners of war, slave laborers, concentration camp inmates, ex-soldiers, Germans expelled from Eastern Europe, and refugees who had fled the Russian advancea congeries of moving humanity. A frenzy. Apt subjects for Hieronymus Bosch. But he was nowhere to be found.

And so, silence and frenzy.

Sights and sounds for a century.

The year 1945 stands at the center of our century and our meaning.

How did we get there, to this silence in the eye of the storm, to this moment of incomprehension when life was reduced to fundamental form, scurrying for survival?

We arrived twice: in reality, and subsequently in collective remembrance. The reality is now beyond our reach, the remembrance constitutes history. Our historical sense is derived in turn from two directions: from the buildup that were the events of the pre-1945 past, with its inherent notions of agency and cause, and from the confusions of our own end-of-century, end-of-millennium present, with its immediacy and contradiction. We arrive, on the one hand, from a prior imperial age whose gist was coherence, and on the other hand, from a postcolonial present whose logic is fragment. The past and present converge in 1945 with poignancy and symbol sans pareil.

Most of us arrive at 1945 not as agents, leaders, soldiers. We arrive as hangers-on or as victims, in crowds, pushed and pulled by events over which we feel we have no control. But as Franz Kafka suggested earlier in this century, the very notion of the victim is redolent of compromise and guilt. Violence was perhaps prefigured in the cultures of the victims, in the provocation they represented. At the same time the violence of 1945 remains our violence, our burden, our shame.

But how does one tell a tale that ends before it begins, that swirls in centrifugal eddies of malice, where the margin is by definition the middle, the victim the agent, where the loser stands front and center? Perhaps Theodor Adorno was right. He foresaw the very "extinction of art" because of the "increasing impossibility of representing historical events."

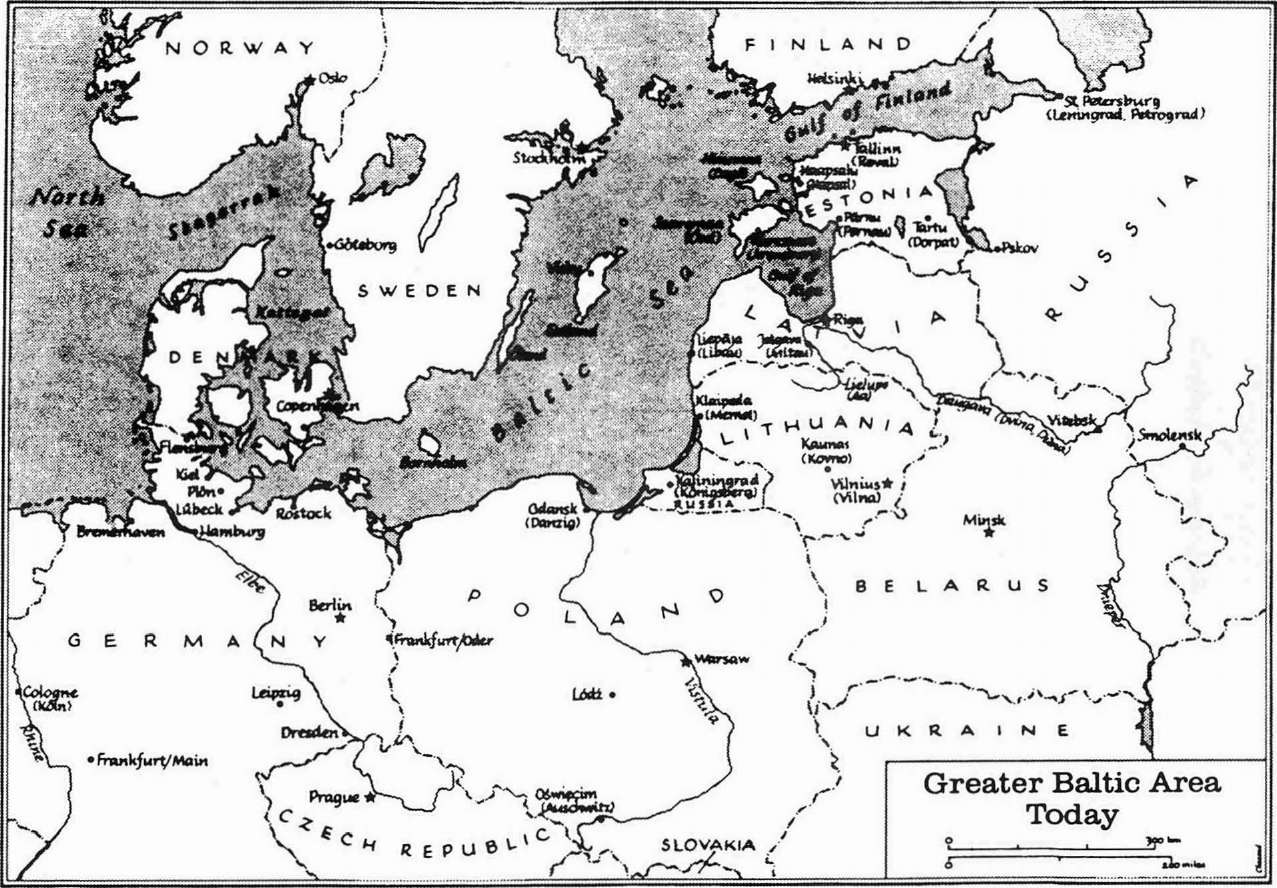

If the tale is to be told, it must be told from the border, which is the new center. It must be told from the perspective of those who survived, resurrecting those who died. It must evoke the journey of us all into exile, to reach eventually those borders that have become our common home, the postmodern, multicultural, posthistorical mainstream. "God, it must be cool to be related to Aztecs," said the Berkeley undergraduate to the Mexican-American writer Richard Rodriguez.

The tale must reflect the loss of authority, of history as ideal and of the author-historian as agent of that ideal. What we are left with is the intimacy not of truth but of experience.

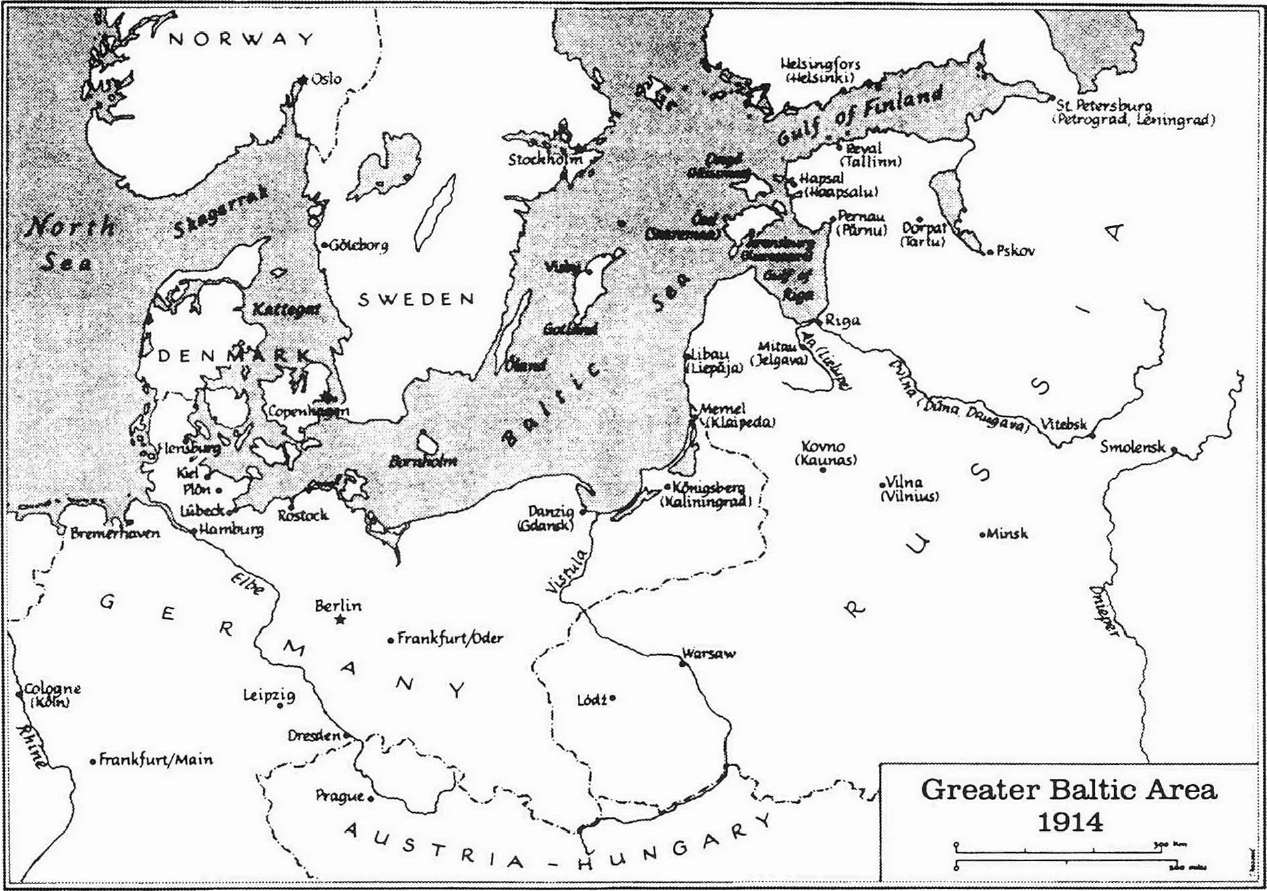

The story, as a result, becomes a pastiche of styles, an assemblage of fragments, appropriate to an age. It becomes a mlange of memory, reflection, and narrative. The tale begins at two extremes and journeys to its center. It begins in the 1850s in the border provinces of western Russia and simultaneously in the intellectual borderlands of contemporary North American academe. It moves both forward and backward, through parallel migrations, disjunctures, and upheavals, to its conclusion in the maelstrom that was Germany in May 1945.

Germany at the end of World War II is the ultimate "placeless" placedefeated, prostrate, epicenter of both evil and grief, of agency and submission. It is here, in a swampland of meaningless meaning, that our century has its fulcrum. It is to Germany in May 1945, to its milling millions, its smashed armies, its corpses and debris, that we must journey.

The principal dramatis personae in this tale of disintegration, and yet liberation, are of necessity the author's familymy family. (In the collapse of category that marks our age, can I present any other list of characters?) We begin in the middle of the last century with Grieta, my maternal great-grandmother, Latvian chambermaid to a Baltic-German baron. She was seduced, made pregnant, and then rejected by her master. Her subsequent life, of spiteful and vengeful disquiet, merged with a burgeoning Latvian self-affirmation that was more often directed at the perceived foe, represented directly by the dominant Baltic-German nobility and in the background by Russian imperial authority, than at self-cultivation.

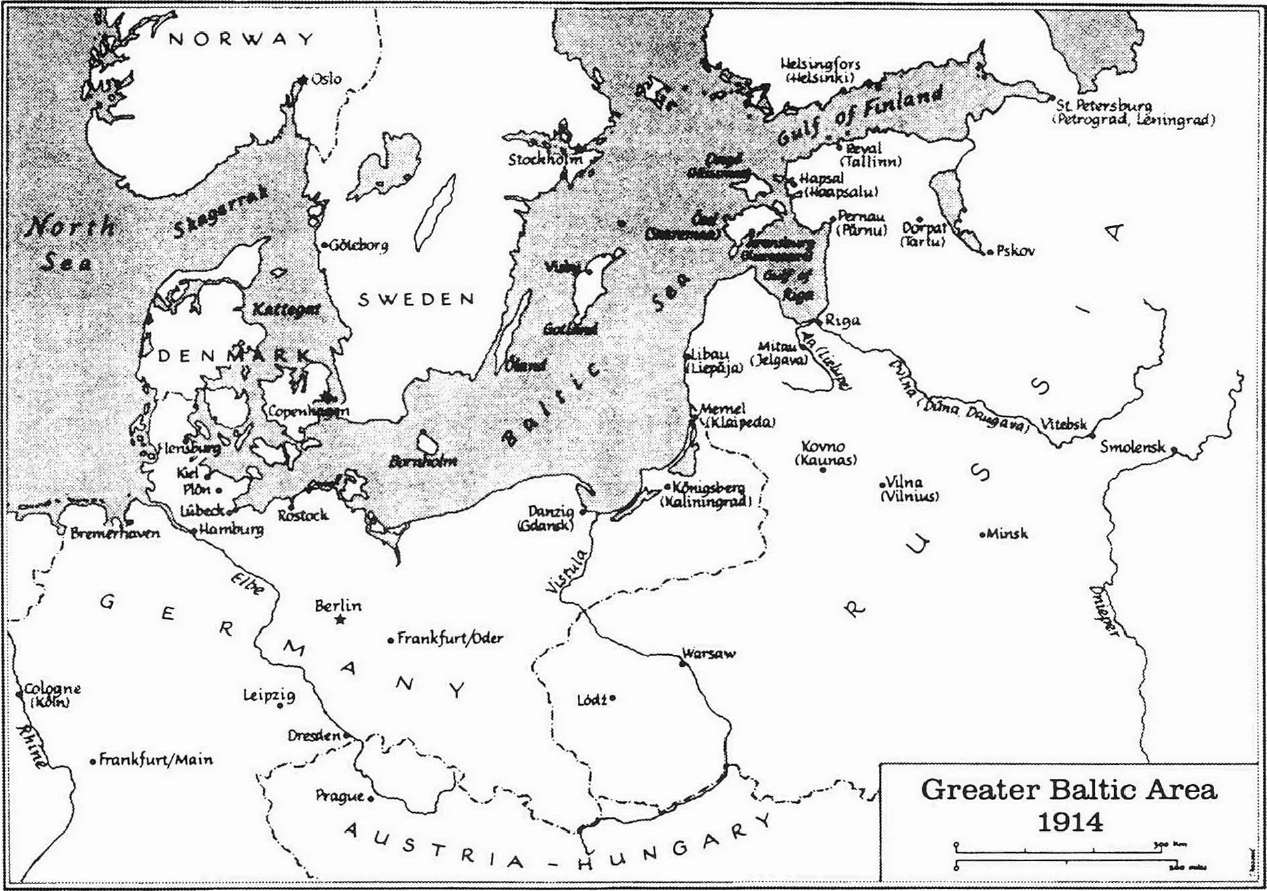

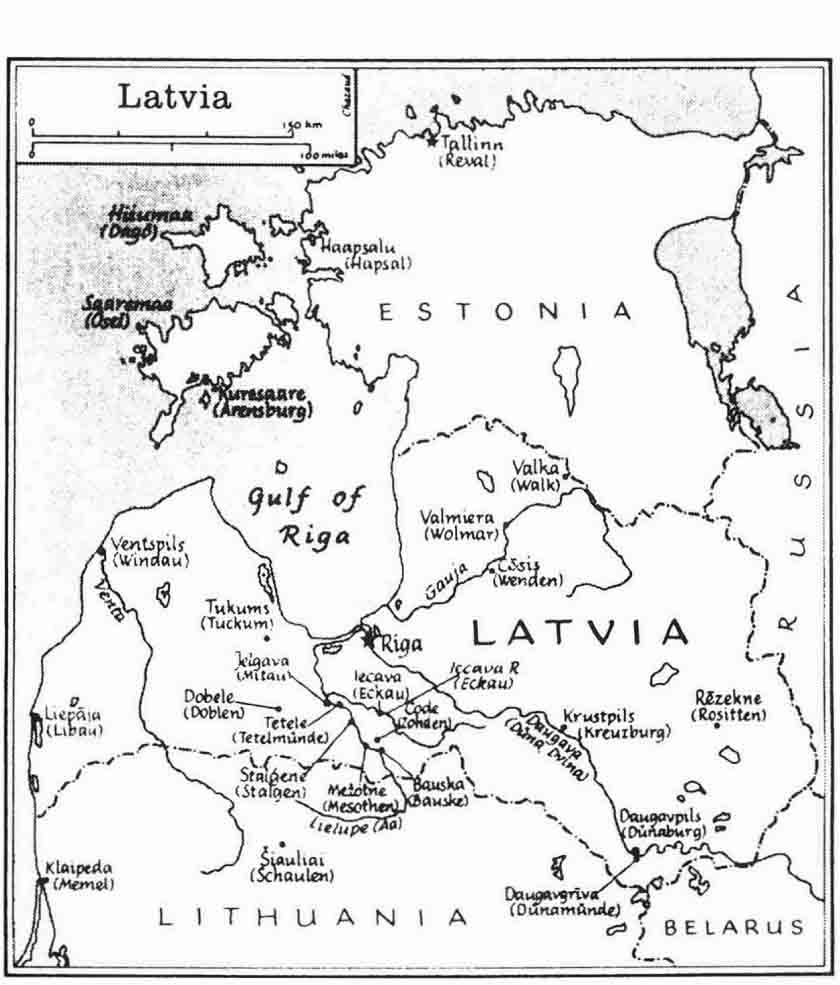

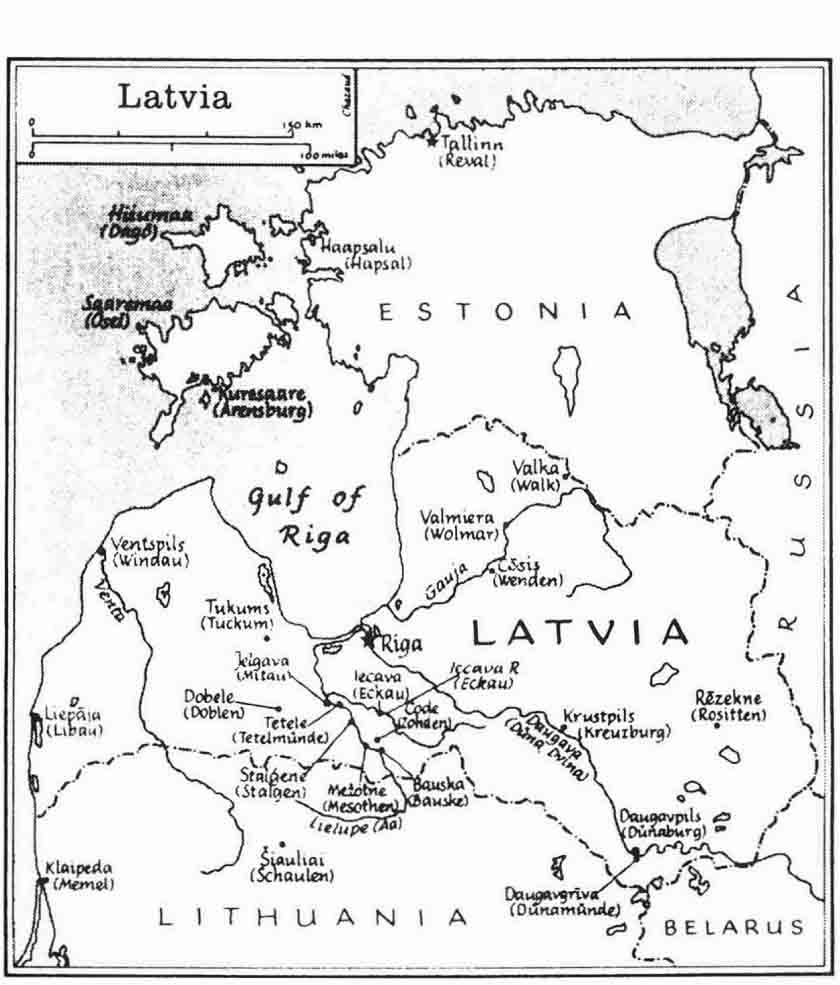

My grandfather, Jnis, born 1874, married the youngest of Grieta's daughters. He used her tiny dowry to set up a small fiacre business in Mitau, the capital of Kurland. This urban-entrepreneurial spirit was again representative of a stage of social, economic, and ethnic development in the Eastern European borderlands that now coincided with the onset of a merciless whirlwind of violence, engendered by imperial rivalries and yet fueled by indigenous interests, toothe Great War and the brutal civil war that followed. Jnis could have been born of Bertolt Brecht's imagination: with his cart and horse he became a latter-day Mother Courage, an itinerant, salvaging life and future for himself and his family amidst the chaos of murderous conflict. In the postwar world, when Latvia achieved independence, owing less to her own effort, significant as that was, than to the collapse of empire (Hohenzollern, Hapsburg, Romanov, Ottoman), Jnis finally got his own plot of land, a few kilometers from Jelgava, the former Mitau.

Next page