Table of Contents

For Spencer, Rebecca, and Trevor.

With all my love.

Southern Maryland.

Washington, D.C.

INTRODUCTION

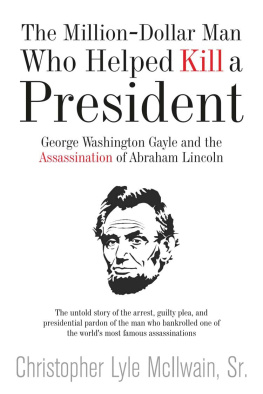

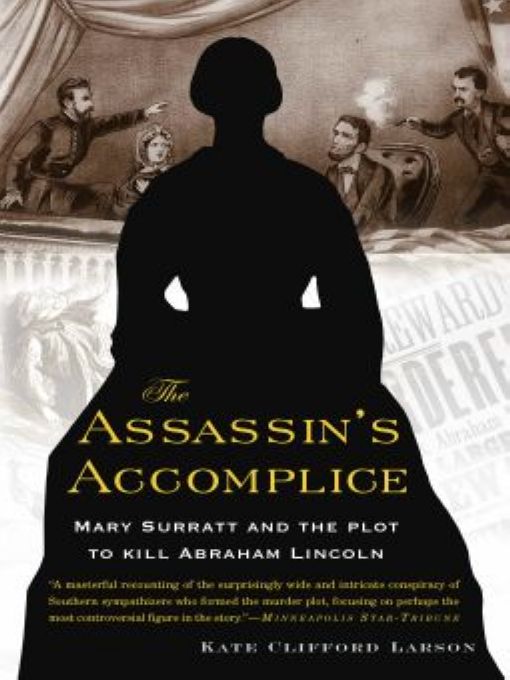

At 1:22 P.M. on July 7, 1865, forty-two-year-old Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt was hanged for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth to murder President Abraham Lincoln. She would be the first woman ever executed by the United States government.

By the summer of 1865, practically every American knew who Mary Surratt was. To them she was either a hard-hearted, manipulative co-conspirator who aided in the plan to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln, or an innocent woman trapped in Booths murderous web and subjected to a vengeful and bloodthirsty military tribunal. Hanged with three male co-conspirators beside her, Marys fatal punishment sent shock waves around the nation. Today, nearly 150 years later, few Americans know her story and still fewer recognize her name.

Mother, widow, businesswoman, and a deeply pious Catholic, Mary Surratt seemed an unlikely assassins accomplice. Until now, the reasons behind her choice to participate in such a deadly scheme have gone relatively unexplored. Looking back into Marys past, however, one might find the seeds of rebelliousness and disloyalty nurtured in a fertile rebel community.

From her birth and upbringing in a modest slaveholding family in a small Maryland town, to her conversion to Catholicism (made much of during and after her trial) and her early marriage to an alcoholic ten years her senior, Marys life story seems unremarkable in its detail. But clues to her fateful decision to befriend and support Lincolns murderer may be found in the deep disruptions brought on by the Civil War and her husbands sudden death in 1862. Left with his massive debts to pay off, Mary may have discovered a strategy for survival: providing a safe haven for Confederate couriers, spies, and ultimately, assassins.

On the day of her hanging, Mary Surratt was the most reviled woman in America. But public opinion shifted again and again from the time of her arrest through the century and a half since her execution.

During the unseasonably hot weeks of May and June 1865, dramatic newspaper reports of Marys trial fed a growing public appetite for revenge and retribution for Lincolns assassination. During the four-week trial, which included the simultaneous prosecution of seven other Booth accomplices, daily news reports from the courtroom exposed the public to the depth of the conspiracy to kill Lincoln and Marys central role in the plot. By the middle of June, when the trial was winding down, most Americans believed Mary was guilty, convinced that the cold, beguiling woman had aided John Wilkes Booth and his co-conspirators.

The Northern press had little sympathy for Mary Surratt during the highly publicized trial. At first, she was portrayed as a willing accomplice in the conspiracy. Some papers described Surratt in almost caricature fashion. An Amazon (she was about five feet, four inches tall and of medium build), they wrote, with black eyes and a small mouthboth attributes, according to the press, of a criminal face. Many of the leading newspapers of the day heartily supported the military tribunals verdict of guilty. The Union had long suffered from the skillful spying perpetrated by cunning and seductive female Confederate agents, leaving little room for empathy for Surratt. To Northerners, her sex and mature age only amplified the perceived depravity of the Southern character.

But Surratts punishment shocked the nation. Within hours of her hanging, people all across the country expressed horror and revulsion over her death. Days later, public sentiment began to dramatically change. For some Americans, Mary Surratt had been wrongfully subjected to a vindictive federal military tribunal. Her supporters accused the military court that tried her and the other co-conspirators with illegally prosecuting civilians. Eager news reporters featured these accusations in their papers, claiming the court suppressed exculpatory evidence and allowed false testimony given by government witnesses against Mary to go unchallenged.

Sympathy for Mary increased dramatically in the weeks after her execution, bolstering what would become a decades-long campaign to restore her reputation and prove her innocence. Though many Northerners believed in her guilt, most apparently never expected she would actually be executed. The outcry was so great it would adversely affect political careers and spark years of scrutiny by those who believed deeply in her innocence. Vilified during the trial of the assassination conspirators, Marys wicked persona was recast into the sorrowful victim, a perfect Victorian mother murdered by immoral and unrestrained powerful men.

Pro-Southern sympathizers saw the trial and execution differently than most Northern citizens, and it is through those sentiments that Marys historic role in the conspiracy has most frequently been retold. The solidarity and determination of Marys supporters helped reimagine and distort the historical record, bolstering strongly held beliefs that a gross miscarriage of justice took the life of an innocent woman.

As a result, the depth of Mary Surratts complicity in the assassination of Lincoln, the fairness of her trial, and the justness of her punishment have been debated since the day of her arrest on April 17, 1865, three days after John Wilkes Booth murdered Lincoln as he sat watching a play at Fords Theatre.

The Assassins Accomplice confronts this historical controversy, detailing Marys role in the assassination, and the chain of events that drove the courts and the Presidents decision to execute her. Thus, The Assassins Accomplice will recover a little-known chapter in American history: the full and dramatic account of the life and trial of Mary Surratt, the woman who nurtured and helped cultivate the conspiracy to kill President Abraham Lincoln.

This biography was begun with the supposition that Mary Surratt was far more innocent of the charges against her than the original trial had determined, and that her unjust hanging was the result of a frenzy of revenge bolstered by a stunned federal government determined to exert its power. Even a woman would not escape the governments single-minded goal to avenge Lincolns murder. But the research itself led to an altogether surprising conclusion: Mary Surratt was not only guilty, but was far more involved in the plot than many historians have given her credit for.

Most contemporary historians of the Lincoln assassination now generally agree that Mary Surratt was involved in the conspiracy to some degree. They have, however, failed to examine her specific actions, her motives, and the broader historical implications of her role in the scheme. This is, in some ways, understandable. The plot to kidnap Lincoln and, later, to assassinate him and other members of his cabinet was enormously complex and involved many accomplices. There were scores of major and minor characters, mostly male. It is the stuff historians love to research and decipher.