RAPHAEL AND THE ANTIQUE

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Series Editor: Franois Quiviger

Already published

Blaise Pascal: Miracles and Reason Mary Ann Caws

Caravaggio and the Creation of Modernity Troy Thomas

Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art A. Victor Coonin

Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares Nils Bttner

Isaac Newton and Natural Philosophy Niccol Guicciardini

John Evelyn: A Life of Domesticity John Dixon Hunt

Leonardo da Vinci: Self, Art and Nature Franois Quiviger

Michelangelo and the Viewer in His Time Bernadine Barnes

Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life Bruce T. Moran

Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer Christopher S. Celenza

Pieter Bruegel and the Idea of Human Nature Elizabeth Alice Honig

Raphael and the Antique Claudia La Malfa

Rembrandts Holland Larry Silver

Titians Touch: Art, Magic and Philosophy Maria H. Loh

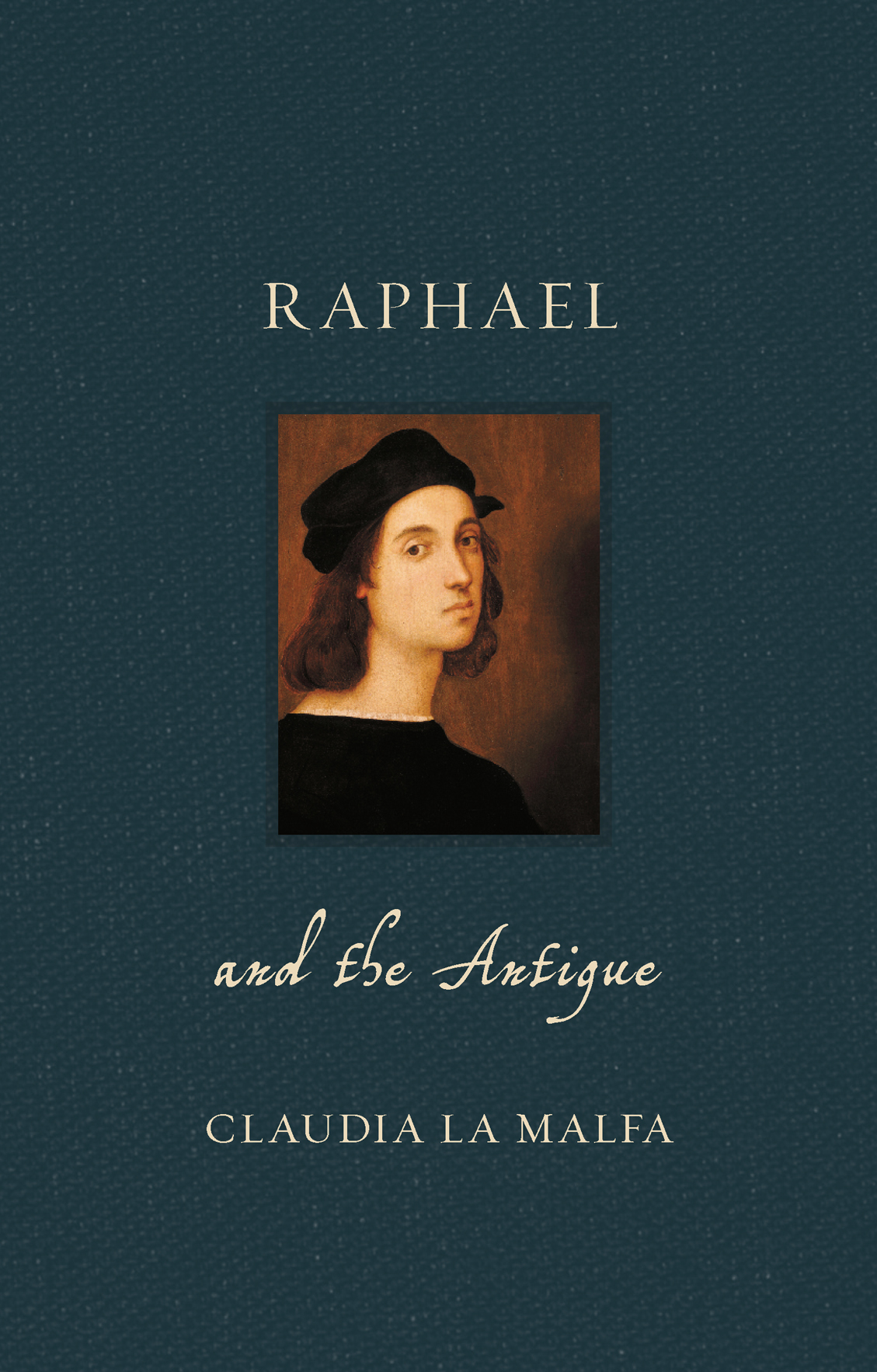

RAPHAEL

and the Antique

CLAUDIA LA MALFA

REAKTION BOOKS

To Sergio

,

. (Sappho, LP 31)

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2020

Copyright Claudia La Malfa 2020

Translation from Italian by Dante Ceruolo and Spencer Gray

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by Toppan Leefung Printing Limited

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789141795

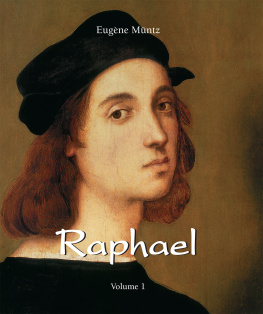

COVER: Raphael, Self-portrait, c. 1506/9, oil on wood; akg-images/Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

CONTENTS

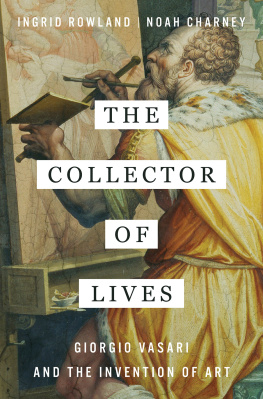

1 Raphael, Pope Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de Medici and Luigi de Rossi, c. 1518, oil on panel.

Introduction

AFFAELLO SANZIO (Urbino, 1483Rome, 1520), known as Raphael, enjoyed the patronage of the most powerful religious and political leaders of the early sixteenth century. Among these distinguished figures were two popes Julius II, member of the della Rovere family, and Leo X, descendant of the de Medici family and a king, Francis I of France. Raphael was held in high esteem by the illustrious families of his lifetime the Montefeltro, the Baglioni, the Doni, the Dei for whom he created works of art enshrining their names in history. In Rome, he garnered prestigious commissions in the households of mighty statesmen: the private apartment of Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena and the villa of Cardinal Giulio de Medici (later Pope Clement VII). He worked for rich bankers, Agostino Chigi and Bindo Altoviti, and painted monumental altarpieces for the historian Sigismondo de Conti and the Bolognese noblewoman Elena Duglioli. Raphael maintained bonds of friendship with pre-eminent men of intellect: the scholar and actor Tommaso (Fedra) Inghirami; the humanist Pietro Bembo; the poets Antonio Tebaldeo, Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beazzano; and the cultured diplomat Baldassarre Castiglione, each immortalized in his sublime portraits. His art was eagerly sought after at the courts of Alfonso I dEste, Duke of Ferrara, and of his sister, Isabella dEste, Marchioness of Mantua, consort of Francesco Gonzaga and sister-in-law of Elisabetta Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino.

AFFAELLO SANZIO (Urbino, 1483Rome, 1520), known as Raphael, enjoyed the patronage of the most powerful religious and political leaders of the early sixteenth century. Among these distinguished figures were two popes Julius II, member of the della Rovere family, and Leo X, descendant of the de Medici family and a king, Francis I of France. Raphael was held in high esteem by the illustrious families of his lifetime the Montefeltro, the Baglioni, the Doni, the Dei for whom he created works of art enshrining their names in history. In Rome, he garnered prestigious commissions in the households of mighty statesmen: the private apartment of Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena and the villa of Cardinal Giulio de Medici (later Pope Clement VII). He worked for rich bankers, Agostino Chigi and Bindo Altoviti, and painted monumental altarpieces for the historian Sigismondo de Conti and the Bolognese noblewoman Elena Duglioli. Raphael maintained bonds of friendship with pre-eminent men of intellect: the scholar and actor Tommaso (Fedra) Inghirami; the humanist Pietro Bembo; the poets Antonio Tebaldeo, Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beazzano; and the cultured diplomat Baldassarre Castiglione, each immortalized in his sublime portraits. His art was eagerly sought after at the courts of Alfonso I dEste, Duke of Ferrara, and of his sister, Isabella dEste, Marchioness of Mantua, consort of Francesco Gonzaga and sister-in-law of Elisabetta Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino.

Raphael engaged in the intellectual exchange of ideas with architects of renown such as Giuliano da Sangallo, Donato Bramante and Fra Giovanni Giocondo. His works were praised by the great masters, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Drer, Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano del Piombo and Titian. His inventions were a constant source of inspiration for the contemporary sculptors Andrea Contucci, il Sansovino, and Jacopo Sansovino. While the artist worked as a painter in his early life, he later diversified as an architect. Yet his vision extended beyond: as an outstanding draughtsman, he supplied designs to sculptors, weavers of tapestries, mosaic makers and ceramicists. Raphael cultivated a keen interest in printmaking, entrusting his drawings to the most gifted engravers of his age, Marcantonio Raimondi, Agostino Veneziano and the experimental Ugo da Carpi. He even turned his hand to poetic creation, albeit with negligible success, leaving a few sonnets of slight account. In close collaboration with Baldassarre Castiglione, he set out to compose his most ambitious literary work, the Letter to Pope Leo X, which contained a description of ancient Rome.

Raphaels epistolary exchanges with his friends and patrons indicate that he was not only cordial and affable in character, but also able to forge close ties of friendship that sprang from mutual respect and affection. His earliest admirers observe that he was a great lover of women. The powerful Cardinal Bibbiena wished to broker a marriage between the artist and his niece. Raphael mentioned the proposal in a letter to his relatives in Urbino, considering it to be propitious; why the marriage did not come to fruition is still unknown. However, most of all he harboured a love for a young woman immortalized in the painting referred to as the Fornarina since the end of the settecento, when the pre-Romantic myth of the humble origins of the Renaissance masters beloved was first fashioned. In the portrait, today in Palazzo Barberini in Rome, the sitter offers herself to the viewers gaze, barely enfolded in a veil revealing the contours of her body, her breasts voluptuously exhibited. In the foreground a velvet armband inscribed with the gilded letters Raphael Urbinas is prominently displayed. The delicate body of the Fornarina is modelled on that of a classical muse.

Some sources recount that the artist succumbed to a viral fever as the result of amorous excess, leading to his death within the course of three days. Raphael was suddenly struck down at the age of 37 and the young master died on 6 April 1520. He left an abiding legacy to which successive generations have repeatedly returned, and bequeathed an artistic heritage beyond compare to posterity. Two qualities of Raphaels art were held in admiration both by his contemporaries and by generations of artists, noblemen, historians and art critics. The first was his dazzling technique in depicting the human figure, cohering itself through the subtle gradations of emotions and the classical rhetoric of gesture and expression. The second was his remarkable invention, whereby narrative is harmoniously orchestrated in a perfect balance between naturalism and monumentality of composition. This fusion of naturalism and classicism was regarded as the most striking aspect of Raphaels art by his earliest admirers and biographers. On his tomb, the epitaph reads:

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

AFFAELLO SANZIO (Urbino, 1483Rome, 1520), known as Raphael, enjoyed the patronage of the most powerful religious and political leaders of the early sixteenth century. Among these distinguished figures were two popes Julius II, member of the della Rovere family, and Leo X, descendant of the de Medici family and a king, Francis I of France. Raphael was held in high esteem by the illustrious families of his lifetime the Montefeltro, the Baglioni, the Doni, the Dei for whom he created works of art enshrining their names in history. In Rome, he garnered prestigious commissions in the households of mighty statesmen: the private apartment of Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena and the villa of Cardinal Giulio de Medici (later Pope Clement VII). He worked for rich bankers, Agostino Chigi and Bindo Altoviti, and painted monumental altarpieces for the historian Sigismondo de Conti and the Bolognese noblewoman Elena Duglioli. Raphael maintained bonds of friendship with pre-eminent men of intellect: the scholar and actor Tommaso (Fedra) Inghirami; the humanist Pietro Bembo; the poets Antonio Tebaldeo, Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beazzano; and the cultured diplomat Baldassarre Castiglione, each immortalized in his sublime portraits. His art was eagerly sought after at the courts of Alfonso I dEste, Duke of Ferrara, and of his sister, Isabella dEste, Marchioness of Mantua, consort of Francesco Gonzaga and sister-in-law of Elisabetta Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino.

AFFAELLO SANZIO (Urbino, 1483Rome, 1520), known as Raphael, enjoyed the patronage of the most powerful religious and political leaders of the early sixteenth century. Among these distinguished figures were two popes Julius II, member of the della Rovere family, and Leo X, descendant of the de Medici family and a king, Francis I of France. Raphael was held in high esteem by the illustrious families of his lifetime the Montefeltro, the Baglioni, the Doni, the Dei for whom he created works of art enshrining their names in history. In Rome, he garnered prestigious commissions in the households of mighty statesmen: the private apartment of Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena and the villa of Cardinal Giulio de Medici (later Pope Clement VII). He worked for rich bankers, Agostino Chigi and Bindo Altoviti, and painted monumental altarpieces for the historian Sigismondo de Conti and the Bolognese noblewoman Elena Duglioli. Raphael maintained bonds of friendship with pre-eminent men of intellect: the scholar and actor Tommaso (Fedra) Inghirami; the humanist Pietro Bembo; the poets Antonio Tebaldeo, Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beazzano; and the cultured diplomat Baldassarre Castiglione, each immortalized in his sublime portraits. His art was eagerly sought after at the courts of Alfonso I dEste, Duke of Ferrara, and of his sister, Isabella dEste, Marchioness of Mantua, consort of Francesco Gonzaga and sister-in-law of Elisabetta Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino.