For Tony, Lucy, and Zoe, with all my love

Publication of this book has been supported by the Lila Acheson Wallace-Readers Digest Publications Subsidy at Villa i Tatti.

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association.

Publication of this book has been supported by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation Fellowship in Renaissance Art History of the Renaissance Society of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DElia, Una Roman, 1973 , author. Raphaels ostrich / Una Roman DElia.

pages cm

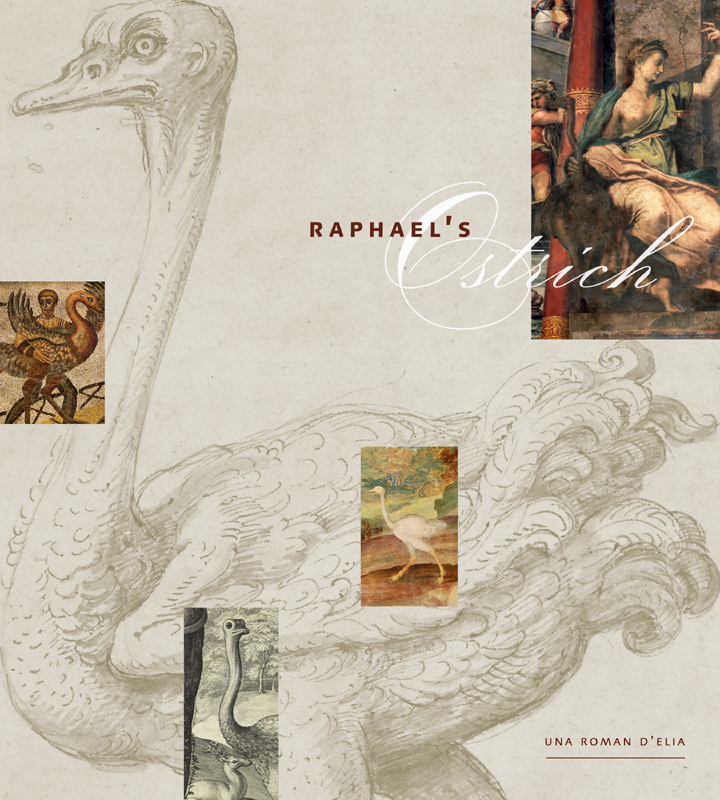

Summary: Explores artistic depictions of the ostrich from ancient Egypt to the Renaissance works of Raphael. Traces the history of shifting interpretations given to the ostrich in scientific texts, literature, and religious writingsProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-271-06640-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Ostriches in artHistory.

2. Art, Renaissance.

3. Painting, Renaissance.

4. Raphael, 14831520Criticism and interpretation.

I. Title.

N7668.O88D45 2015

709.024dc23

2015003564

Copyright 2015 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z39.481992.

Additional credits: page 12, detail of man bringing an ostrich up a ramp, mosaic, early fourth century ()

Contents

I owe so much to so many generous peoplethis book was truly a pleasure to research and write. As I come to write this, I am yet again overwhelmed at their erudition and kindness and at their belief that writing a book on ostriches was a sane thing to do. I carried out the research for this book with the generous support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and had the enormous privilege of spending a year as a fellow at Harvard Universitys Villa I Tattiun grande abbraccio a tutti voi: Amy Bloch, Babette Bohn, Claudia Bolgia, Suzanne Boorsch, Daniel Bornstein, Eve Borsook, Abi Brundin, Lorenzo Calvelli, Chris Carlsmith, Claudia Chierichini, Franoise Connors, Joe Connors, Donal Cooper, Michael Cuthbert, Angela Dressen, Anne Dunlop, Serena Ferente, Francesca Fiorani, Allen Grieco, Martin Kemp, Bob La France, Kate Lowe, Ann Moyer, Deborah Parker, Michael Rocke, Marc Schachter, Carlo Taviani, Louis Waldman, and Joanna Woods-Marsden. Without that time, lovely place, the library, and especially the fellows and staff, I could never have contemplated writing such a wide-ranging book, and I wouldnt be the scholar that I am. While in Florence my family met our Italian familyFede, Fabri, Ale, Paolo, Melania, Marco, Elena, Pietro, e Stella, ci mancate!

It would not have been possible to print this sumptuously illustrated book without the generous support of the Millard Meiss Publication Fund, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation Fellowship, and the Lila WallaceReaders Digest Publication Subsidy from Villa I Tatti. I could not have told this story without these weird and wonderful ostrich images, many of which have not been published before. I am grateful to many individuals and institutions for helping me obtain images, including Elena Fumagalli, Bob La France, Carlo Taviani, Franois Quiviger, Yvonne Elet, Rosanna Di Pinto, Estelle Lingo, Susanne McColeman, and Anna Rita Paccagnani.

I am lucky to have wonderful colleagues at Queens University and want to thank in particular Stephanie Dickey, Janice Helland, Cathleen Hoeniger. I am deeply saddened by the death of David McTavish, my colleague and friend and a generous and knowledgeable expert on Renaissance art, who discussed this project with me for years. I am also grateful to my students and especially to my research assistants Theresa Huntley, Heather Merla, and Susanne McColeman. I have discussed this project with an amazing group of international friends and colleagues whom I wish I could see more often, including Nadja Aksamija, Monica Azzolini, Stephen Campbell, Kathleen Christian, Filippo de Vivo, Chris Fanning, Charles Hope, Joost Keizer, Daniel Kokin, Bob La France, Stuart and Estelle Lingo, Margaret Meserve, Aimee Ng, Emily OBrien, Lino Pertile, Franois Quiviger, Fabrizio Ricciardelli, Leslie Ritchie, Luke Roman, Mary Claire and Michael Vandenberg, and Tristan Weddigen.

Three formidable scholars and dear friendsAbi Brundin, Anne Dunlop, and Stuart Lingoall read the entire manuscript before I sent it to the press, and each helped me cut through the mire and sharpen the argument. They showed me what I wanted to say. I could not have asked for more sympathetic, generous, knowledgeable, and thoughtful readers than the ones chosen by the press, Marcia Hall and Paul Barolsky. Another creative and rigorous scholar, Ken Gouwens, who is also an old friend, read the entire manuscript before copyediting and helped me avoid innumerable errors and infelicities. At the press, Ellie Goodman has been quite simply an ideal editoropen-minded, generous, and criticaland Charlee Redman has been amazingly helpful in countless ways. I am also grateful for Keith Monleys sensitive and smart copyediting. After all of this incredible help, any remaining errors are obviously my own.

I talk to my parents, Timmie and Michael Roman, on the phone every night, and we never run out of things to say. But when I try to express what my husband, Tony, and our beautiful, strong, and smart daughters, Lucy and Zoe, mean to me, for once in my life, Im speechless.

Raphael Is Dead. Long Live Raphael!

When Raphael died suddenly in his thirties, on Good Friday in 1520, reportedly after being made feverish from too much sex, writers quickly enshrined the somewhat dissolute painter by comparing him to

Tomb of Raphael, marble and other stones, begun in 1520, Pantheon, Rome.

Raphael, Transfiguration, oil, 151620. Musei Vaticani, Vatican City.

From the seventeenth century until well into the twentieth, the Transfiguration was hailed as Raphaels greatest work.

The Raphael that is famous today and was idolized in the nineteenth century is a much simpler and more anodyne painter than the one that was divinized in 1520. All of those small dear Madonnas so celebrated for their sweetness were early modest works, probably made on spec, before he had received any of his grand commissions, and so were not much reproduced or widely praised in his day. The School of Athens, now famous for its seemingly perfect evocation of a harmonious classicism, was also little known, as it was painted in one of the popes private apartments and so, unlike the