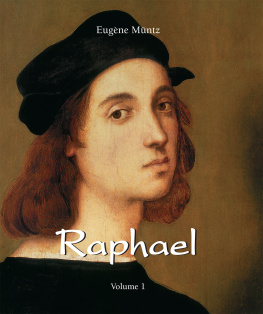

Self-Portrait with Giulio Romano, probably 1520

In memory of Sarah Vernon-Hunt

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all those with whom I have discussed Raphael over the decades, especially Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Dominique Cordellier, to whose magisterial Inventaire (co-written with Bernadette Py) of drawings by and after Raphael in the Louvre I constantly return, and also to Tom Henry, with whom in 2012 I collaborated on an exhibition devoted to Raphaels later work. More immediately, I am profoundly indebted to Sheri Shaneyfelt, David Ekserdjian and James Obelkevich, all of whom, with a commitment over and above the call of friendship, read and commented on earlier versions of this book as a whole or in part. I also wish to thank Dr Guido Cornini who, most generously and in advance of his own publication, supplied me with the previously unavailable dimensions of the four great narrative frescoes in the Sala di Costantino.

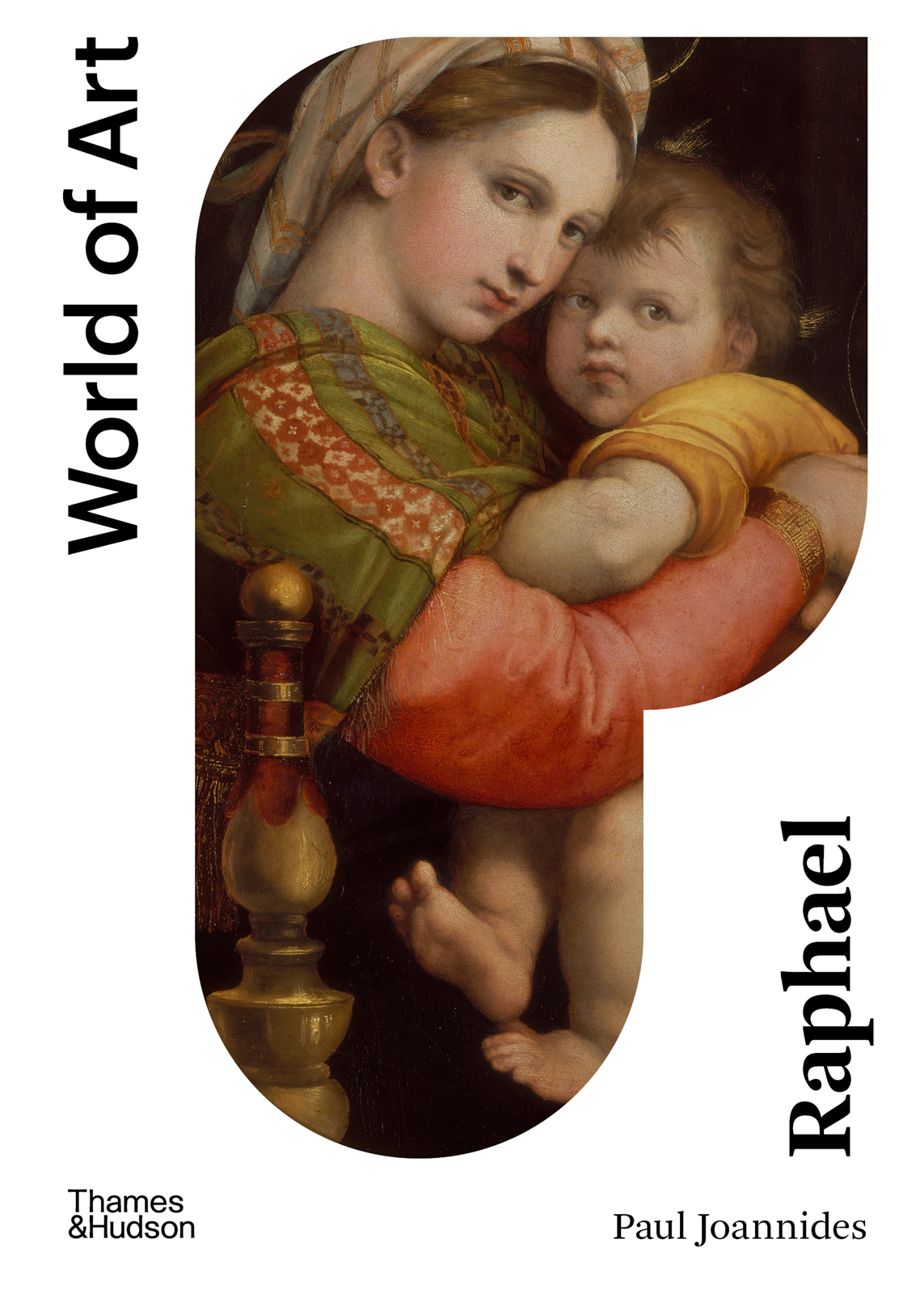

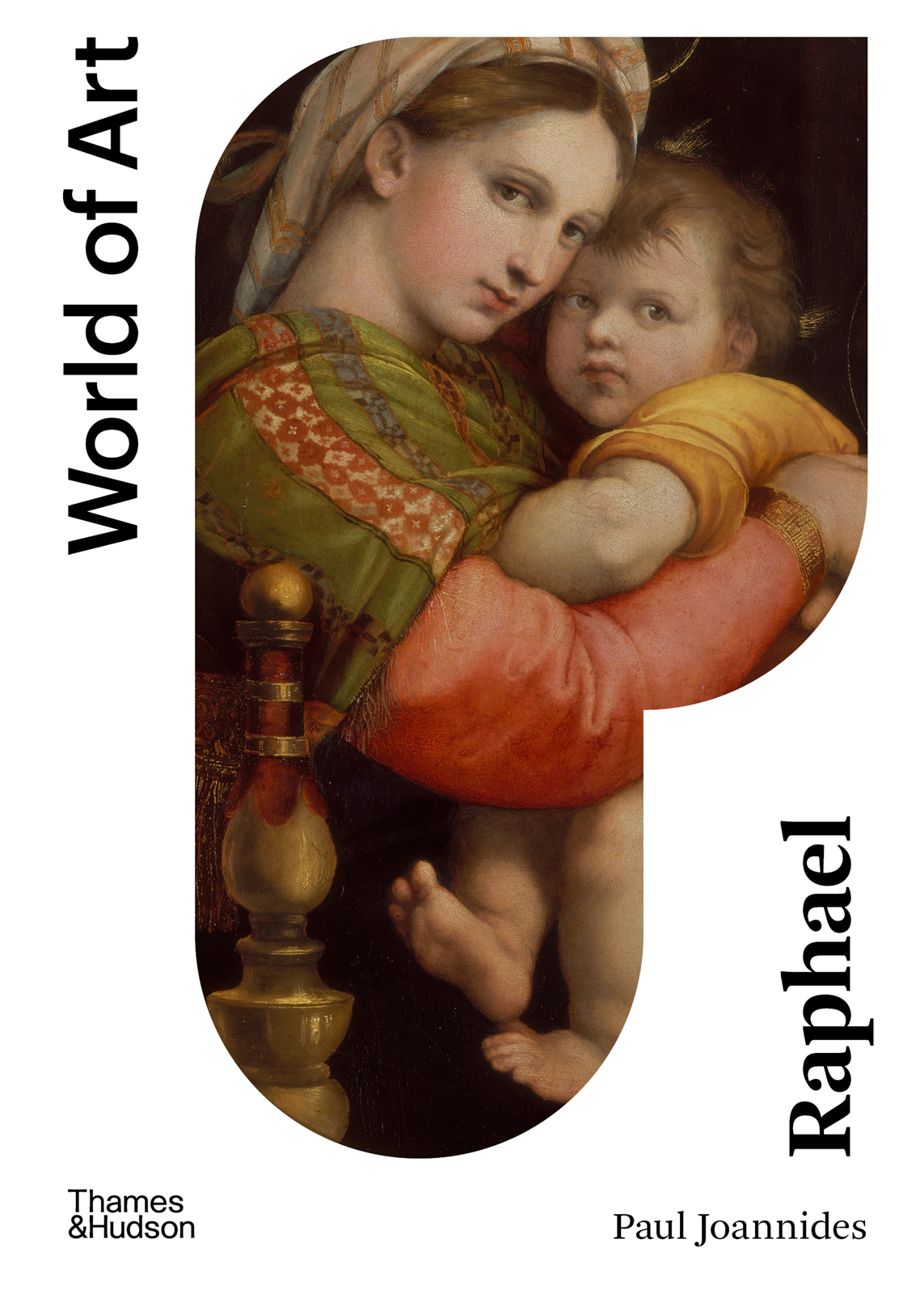

About the Author

Paul Joannides is Emeritus Professor of Art History in the Department of History of Art at the University of Cambridge. He is a specialist in the painting, sculpture, drawing and architecture of the Italian Renaissance. His publications include The Drawings of Raphael (1983); Masaccio and Masolino (1993), Titian to 1518 (2001), Michel-Ange: lves et Copistes (2003) and The Drawings by Michelangelo and his Followers in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (2007). He curated The Influence of Michelangelo: Drawings from Windsor Castle, an exhibition shown at various venues in the UK and the USA from 1996 to 1997, and (with Tom Henry) Late Raphael, shown in the Prado and the Louvre in 2012 and 2013.

Contents

The aim of this book is to provide an introductory account of Raphaels work and life that students and those interested in Renaissance art might find useful. There exist many general books on Raphael in many languages, including excellent ones in English among which that by Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny is exemplary but Raphael was so protean in style, so multifarious in his artistic, architectural, archaeological and theoretical interests, so massively productive and so inventive that no single account can illuminate his work more than partially. Critics and historians respond diversely to his work and to different areas of it, and emphases vary so greatly from one to another that one can read many studies of Raphael consecutively without fatigue and with little sense of repetition.

Self-Portrait, 1499 or earlier

The starting point of this book is what Raphael drew and painted and designed. The product of many years of studying the work of Raphael and his associates in the original, it concentrates on Raphaels changes of style, his responses to other artists, and the vast expansion of his artistic interests during the twelve years he lived in Rome. It also addresses aspects of his collaboration with others, notably Giulio Romano, whom Raphael, according to Vasari, loved like a son an artist of a genius and universality that nearly equalled Raphaels own, and whose activity within Raphaels organisation has often been underestimated.

The book is organised chronologically but from the beginning of the Leonine period, as all writers have found, a purely chronological narrative is impractical. Increasingly, Raphael executed and supervised more than one project simultaneously, and to switch from one to another would create confusion and blur appreciation of them. Hence in this book several chapters are devoted to individual or interrelated schemes, while others focus on artistic categories, such as Raphaels moveable paintings. There is also a chapter on Raphaels architecture, which has links with some aspects of his painting but whose nature requires separate treatment. Other themes, such as Raphaels projects for Agostino Chigi, run across chapters.

Despite many years of work on Raphael, I was surprised, as I was writing, by how much I did not know. The many lacunae that the reader will find should be taken as incentives to investigate further the literature on Raphael, much of which is deeply rewarding, and, more importantly, to explore those areas of his work that may be less familiar but whose treasures are manifold. Like Rubens, like Bernini, Raphael is a continent still not fully mapped.

Study of Raphael has benefited since the 1960s from the work of many able scholars, but four of them can legitimately be described as great. Philip Pouncey and John Gere, in their 1962 catalogue of drawings by Raphael and his circle in the British Museum, established secure stylistic divisions between the drawings of Raphael and those of his major associates. In a series of articles and books published from 1959 until his death in 2003, John Shearman expanded greatly our knowledge of Raphaels work and his thought processes. A scholar of extraordinary range and erudition, he was particularly successful in establishing the physical, intellectual and theological contexts in which Raphael worked. Shearmans contemporary, Christoph Frommel, whose knowledge of all aspects of Renaissance architecture and much else is unequalled, has reconstructed and clarified Raphaels achievement in a field that presents some of the thorniest of all art historical problems. To these four names, many would add that of Konrad Oberhuber, who worked primarily on Raphaels drawings and, less intensely, his paintings. But Oberhubers achievement is equivocal. In often enlightening writings of the 1960s and 1970s he added the portrait of Julius II and several drawings to Raphaels oeuvre and, in the wake of Pouncey and Gere, shone light on the work of Raphaels assistants, especially Gianfrancesco Penni and Giulio Romano. But from the early 1980s he effectively rejected his earlier conclusions and increasingly gave directly to Raphael almost all the drawings and paintings that he had previously believed to be by assistants. Oberhubers expansionism was not the result of new discoveries or the coherent rearrangement of existing evidence; it came from a spiritual revelation. Drawings and paintings formerly considered no more than competent suddenly become masterpieces worthy of Raphael. Oberhubers vision, initially greeted with incredulity, has come to exercise considerable influence and has now, in some quarters, become orthodoxy. However, it is the present writers conviction that the ever inclusive approach of Oberhuber and his followers is misguided and fails to understand the work of both Raphael and his associates. The attributions and stylistic judgments advanced in the present book maintain and, where necessary, develop from a consensus achieved between c. 1960 and 1980.

Throughout his life, when Raphael signed his paintings it was generally in the form Raphael Urbinas; and when writing of him, his contemporaries rarely failed to mention his birthplace. Urbino, and particularly its court, was a permanent resource for Raphael. It was there, among the writers, intellectuals, diplomats, aristocrats and members of the power elite who frequented the court, that Raphael made some close and influential friends and established long-lasting contacts.

Next page